- Paper Title: The Starspots-Transit Depth Relation of the Evaporating Planet Candidate KIC 12557548b

- Authors: H. Kawahara et al

- First Author’s Affiliation: University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan

- Journal: Astrophysical Journal Letters (submitted)

Overview

There is a small planet candidate, likely rocky, that looks like it’s being vaporized. The authors of this paper show evidence that this evaporation might be related to stellar activity, not just the planet’s proximity to its star.

In Depth

In 2012, a Kepler planet candidate, KIC-12557548b, was observed that displayed variations of 30% in its apparent radius. The explanation put forward to explain this was that the planet was evaporating. If the planet evaporates faster, then it puffs up due to the cloud of gaseous matter coming off the planet and appears to be larger. The escape rate derived was one Earth mass per billion years.

This planet’s incredible proximity to its host star, with an orbital period of just 0.65 days and a temperature of order 2000 K, would at first glance seem to bear this out: surely it must be vaporizing like ice cream under a blowtorch. However, upon closer inspection this is not necessarily the case. When another team ran the numbers, it was hard for the energy input from the host star alone to explain the degree of evaporation.

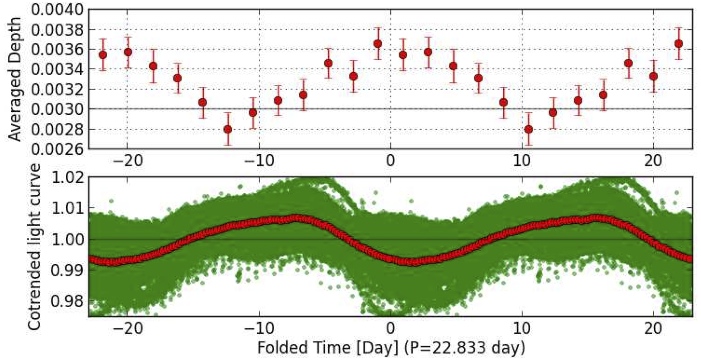

The authors of this paper took a closer look at the data. They benefitted from having more data than the earlier teams by virtue of additional years of Kepler observatons at the time they did their work. They looked closely at the variation in the transit depth of the planet with time (Figure 1-top). They also removed the transit signal from the data and examined the flux of the star over time (Figure 1-bottom). If one assumes the stellar flux variations to be driven by stellar features (e.g. starspots) rotating into and out of view, then the period of the flux variations can be taken to be the stellar period. When executing this procedure, the team found a period of 23 days, within the bound set by spectroscopic observations of how fast the star was rotating.

Figure 1: At top, transit depth vs time, binned. At bottom: stellar light-curve with planetary transit removed. Note the negative correlation between stellar flux and transit depth.

A remarkable correlation emerges when comparing these datasets. The transit depth shows periodic variation on the same timescale as the putative stellar rotation period! This is suggestive: could some kind of stellar activity be driving planetary evaporation?

The authors think so. They hypothesize stellar activity due to a massive starspot could be responsible for the evaporation of the planet. This would also explain why the planet seems largest (i.e. is evaporating the most) when the stellar flux is lowest: the stellar flux is low because the planet-vaporizing starspot has rotated into view. Previous work has demonstrated that large starspots can plausibly be stable on a timescale of years.

How is this starspot vaporizing this planet? The authors consider two explanations. First, starspots often generate large amounts of extreme-ultraviolet (XUV) radiation due to magnetic reconnection. The authors show this to be a plausible explanation assuming very high XUV flux and very high efficiency in the relevant processes. However, further study is needed. Another possible explanation is the energetic electrons released by reconnection. The authors draw on recent work that indicates this too could drive planetary vaporization.

In sum, the apparent evaporation of this planet candidate may plausibly be due to stellar activity, not the illumination of the host star.

I guess my question for them is this… They see matter moving between objects. Something small about planet size is changing the light frequency/intensity as it rotates. Maybe I am not understanding them but, it sounds like they are saying the stars characteristics appear every 23 days but the planetary size object orbits every .65 days. With that information this sounds like a small black hole is circling a star and the matter moving between objects is actually the stars material being stripped off by the black hole and the intensity each stellar rotation is maybe a coronal hole in its magnetic field allowing a greater amount of material to be stripped as it passes the black hole. Of course I’m not observing and don’t have the data but, its just an alternate interpretation from the information you have provided. Like I said I don’t know for sure. Just wondering if this is a possibility?

Hi Dennis,

Thanks for your comment!

A black hole orbiting the star would have imprinted a number of strong signatures on the signal. For example, the light from the star would be displaying evidence of relativistic beaming, an effect of general relativity that would make the star periodically seem to become much brighter. We don’t see these effects, ruling out compact objects like black holes.

Even more importantly, an object like a black hole at that distance would tear the star apart. The fact that the star is not being disrupted places an upper limit on the mass and density of the object, ruling out compact objects like a black hole.

At present time, a planet remains the best explanation for the effects seen.

-Sukrit