- Title: Eccentric Jupiters via Disk-Planet Interactions

- Authors: Paul C. Duffell and Eugene Chiang

- First Author’s Institution: University of California, Berkeley

- Status of Paper: Submitted to ApJ

Rather than perfect circles, the orbits of most planets are elliptical to varying degrees, ranging from nearly circular to oblong-shaped. The “circularity” of a planet’s orbit is referred to as eccentricity (e) and ranges from 0 (circular) to 1 (elliptical). Eccentricity measures how much a planet deviates from a circular orbit. While planets in the Solar System have low eccentricities (e < 0.05), most extrasolar planets display highly eccentric orbits like those of comets.

What are the mechanisms that give rise to planet eccentricities? Planet-planet interactions (when two or more planets in nearby orbits disturb each other) are thought to be one cause, especially for highly eccentric orbits. For moderate eccentricities and/or lone planets with no nearly stellar or planetary perturbers, astronomers turn instead to disk-planet interactions (where disk refers to protoplanetary gas disk). In today’s paper, the authors analyzed a catalog of single giant planets and found a substantial fraction of them to have low-to-moderate (e~0.01 to ~0.15) eccentricities. They investigated the origin of these eccentricities by invoking disk-planet interactions.

Disk-planet interactions are mediated by tidal waves. The orbital motion of a protoplanet will carve out a gap in the protoplanetary disk and perturb it by awakening waves. These tidal waves excite various resonances at different locations in the disk, which then induces angular momentum exchange between itself and the forming planet. Over time, the orbital elements of the planet will change from this subtle interaction. Eccentricity driving via disk-planet interactions is a little more complicated than this, as demonstrated by a related classical paper, Goldreich & Sari (2003). Among the many resonances that are excited in the disk, some damp eccentricity while others amplify it. In order to excite eccentricity, Goldreich & Sari (2003) demonstrated analytically that a planet needs to have its initial eccentricity exceed a threshold value and carve a deep enough gap in the disk such that eccentricity-damping resonances are weaker than eccentricity-amplifying ones. However, the claims of Goldreich & Sari (2003) have never been studied numerically.

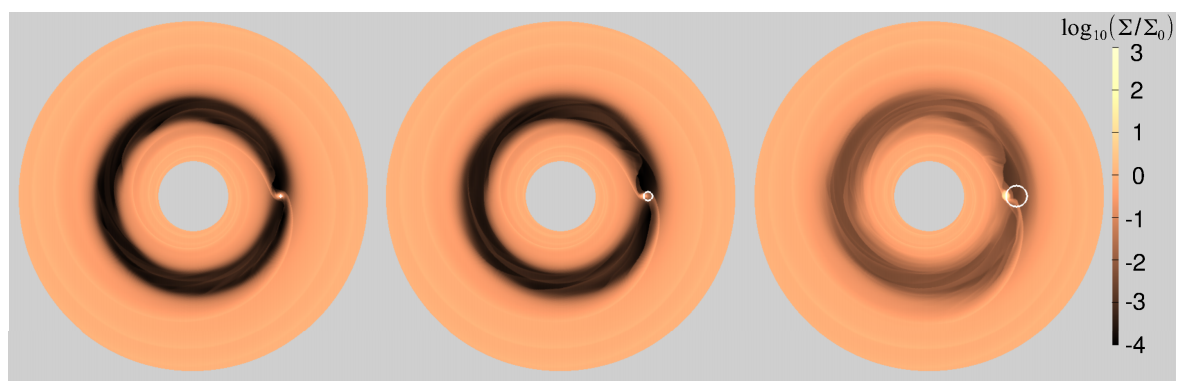

The authors of today’s paper examined low-to-moderate eccentricity driving by disk-planet interactions through 2D simulations and later compared their numerical results with analytical studies. They forced their planet to live in a fixed orbit of a certain semi-major axis and eccentricity, as shown in Figure 1 and ran their simulations until the disk relaxed to a relatively steady state. The disk interaction on the planet (the torque exerted by the disk on the planet) is represented as the rate of change of the planet eccentricity, ė, as a function of eccentricity e. The main takeaways from the paper are shown in Figure 2, where we find eccentricity excitation occurs only within a small range of initial e. For very low e (< 0.04) and e > emax (~0.07), ė < 0 and eccentricity is damped. There is strong eccentricity damping (large negative ė) beyond e > 0.1, and this is due to the planet crashing into its gap walls causing the gap to be filled up and erased.

Fig 1 – Visualizations of the disk-planet systems employed by the authors. The three panels refer to three different planet eccentricity: e = 0.01, 0.05, and 0.12 from left to right. The surface density of the disk is color-coded according to the color bar on the left.

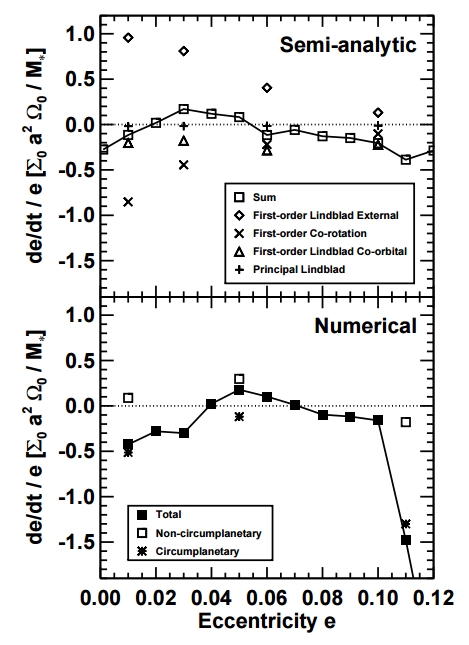

Fig 2 – Change of eccentricity (ė) as function of e. Eccentricity is damped (negative ė/e) for e < e_min ~ 0.04 and e > e_max ~ 0.07, but excited (positive ė/e) in between. Note the small ranges of eccentricity that allow for eccentricity driving. When the planet collides into the gap walls at e > 0.1, eccentricity is strongly damped.

The authors applied the theory of disk-planet interactions to compare with their numerical results. Specifically, they computed the contributions from various resonances to ė. The strongest resonances that affect ė are known as the first-order Lindblad external resonances (exciting e) and the first-order co-rotation resonances (damping e). Lindblad resonances occur at the disk natural frequencies, and Lindblad external resonances refer to when the disk rotates slower than the perturbing planet. Co-rotation resonances happen when the disk material orbits along with the planet, ie at the same orbital frequency. Figure 3 compares results from simulations and analytical theory. The authors noted the broad similarity between their analytical calculation and numerical results in that eccentricity driving happens only after you exceed a small threshold e value. The largest difference happens at the largest e values (considered here), where the eccentricity is much more strongly damped numerically than theoretically. While the authors conceded that linear theory cannot fully describe the complex dynamics of the interaction, numerical perks such as grid resolution and smoothing can also contribute to this discrepancy.

Fig 3 – The top panel is change of eccentricity ė as function of e calculated semi-analytically while the bottom panel shows the numerical result (same plot as figure 2). The different markers in both panels refer to various resonances that contribute to eccentricity evolution. Both analytical and numerical results show that eccentricity driving happens only if the planet exceeds a small threshold e value. The largest difference happens at e > 0.1, when numerical result shows a huge plunge compared to theory.

As a conclusion, the authors demonstrated that orbital eccentricities can be excited by disk-planet interactions, although eccentricities cannot be driven indefinitely. When the planet collides into the gap walls, eccentricity is catastrophically damped — this sets an upper limit on eccentricity amplification. Although their numerical study only concurs broadly with analytical theory, it would be interesting to see if their 2D numerical results survive in 3D, as this will strengthen their case for explaining low-to-moderate eccentricities in giant planets without resorting to planet-planet interactions.