On Friday, many other scientists and I, both male and female, spent our mornings getting angry at a youtube video. The video in question, entitled “Science: It’s a Girl Thing,” was the launch video for an EU campaign to get more young women interested in science. It was posted Thursday and taken down Saturday due to the furor that erupted within the first twenty-four hours of its release.

The video was mirrored, so if you haven’t seen it already, why not spend 53 seconds getting up to speed:

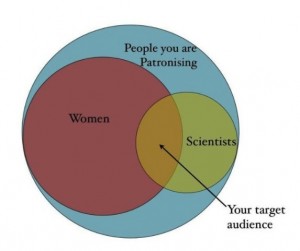

The goal of the video is to appeal to young women and show that science isn’t solely the purview of old men in lab coats. The reason for the negative reactions is that it tries to combat stereotypes with an equally damaging stereotype: being a woman is the same thing as powder brushes and strutting around in high heels. And even though the commission took the video down, the pink lipstick writing (with the “i” in science replaced with a lipstick tube) remains on the commission’s website. (Remind me: what does pink lipstick have to do with science?)

There have been many excellent responses (not to mention the active twitter hashtag #sciencegirlthing) so my goal here is not to reiterate the arguments and reactions of so many, but to collect those that I’ve found particularly interesting.

In my initial google searches, I came across two other Science: It’s a Girl Thing! campaigns that look interesting. The Educational Equity Center has a collection of science activities for young children, which are free to download from their website. Texas Tech, through its IDEAL outreach program, has a residential science camp for middle and high school girls (pdf brochure here). In addition, the campaign in question does actually have some good resources on their site, in particular, profiles of real women in science, including astronomer Yael Naze.

” If you want to get young women excited about science, show them how awesome science is and show them the real women who do that science.” – Dr. Isis

Of the dozens of blog posts written over the past few days, there were two that I particularly liked (and which also made me feel better about the world). This one, by a female researcher in physiology, who goes by @drisis, expresses the author’s indignations at the synthesis of “girls,” fashion and science. Astronomy PhD Nicole Gugliucci (@NoisyAstronomer) discusses her reaction to the video and the related topic of feminine role models in this Skepchick blog post. Finally, Dr. Meghan Gray presents her views in this well-reasoned interview.

Nicole touches on a related topic that has also been the subject of recent science social media buzz: the effectiveness of feminine role models. Some have argued that the EU’s approach to attracting girls to science could work: most of the outrage has come from women who are themselves scientists, but how would a young women not already interested in science react? It turns out there was a recent paper published on this very topic, entitled “My Fair Physicist? Feminine Math and Science Role Models Demotivate Young Girls.” The paper is not available for free, but the title and the abstract get the point across: using overtly feminine role models does not get young girls interested in science. The abstract’s summary of the paper’s two studies is copied below:

- Study 1 showed that feminine STEM role models reduced middle school girls’ current math interest, self-rated ability, and success expectations relative to gender-neutral STEM role models and depressed future plans to study math among STEM-disidentified girls. These results did not extend to feminine role models displaying general (not STEM-specific) school success, indicating that feminine cues were not driving negative outcomes.

- Study 2 suggested that feminine STEM role models’ combination of femininity and success seemed particularly unattainable to STEM-disidentified girls.

When I read the article, I had a similar reaction to graduate student Kate Follette’s, who eloquently expressed her point of view in this blog post. Kate, like me, is involved with science outreach to middle school girls and considers herself to be a “feminine” STEM role model. Are we demotivating the girls we are hoping to inspire? Kate thought about the study further and has decided the jury is still out. In her blog post, she discusses her concern with the way the studies are conducted. She also points out that in the studies, femininity is equated with wearing pink and liking fashion magazines, a narrow definition that doesn’t sit well with either Kate or me. (I also wonder how boys would respond in the same situation, and how all children would respond to a stereotypically masculine role model).

Now, neither Kate nor I are social scientists, but Dr. Marie-Claire Shanahan (@mcshanahan) is a professor of science education and communication. She summarizes the study and also expresses her distrust of the conclusions from the second study, in a thoughtful blog post. She also encourages us to be mentors and offers a few tips. I don’t want to try to summarize the excellent points she makes, so I’ll just recommend her post.

My conclusions from following this story over the past few days are that there are still a lot of difficulties facing women in science, but there are also intelligent, thoughtful people out there (both men and women) who are expressing their views. And while there’s no need to leave my heels at home when I work with middle school girls, there is a need to continue doing outreach and to keep talking about the issues. What do you take away from all this recent discussion on women in science?

OK, I can see why some would find the video troubling, but in my teaching of astronomy, it is rarely the lipstick-toting girl that excels in science — mostly because they seem to think it is too nerdy or too lame. They tend to do just enough to get the grade they want, but rarely show a more passionate interest.

So, the question is, how does the science teaching community get lipstick-toting girls interested in science at the same level as the ones that wear jeans and baggy sweatshirts?

Keep in mind, the fashion world is as big as it is because girls like that stuff and buy into it. It seems that there is little harm to tap into that energy to get more scientists into the world.

I would not have put the kibosh on the add, but I’m an older male and maybe out of touch with reality…

Thanks for your comments, Tony. I think it’s really important to talk about this issue.

Like Kate and Ellie, I am concerned by the categorial division of women into “feminine” and “unfeminine.” Throughout my middle school years especially, I went through epochs of wearing or not wearing makeup, and none of this impacted my performance in the sciences. Even now, as a graduate student, I sometimes wear makeup and skirts, but sometimes do not. This “feminine”/”unfeminine” division seem too sharp to apply to the socially and culturally complex population of women.

I think there is a real danger that if we mentally divide women into artificial groups, we risk predetermining whether they are interested in science before we get to know them. Rather than thinking of my female (or male) students as belonging to one of these categories, I consider each as what she or he is–a unique human being, full of curiosity, and capable of learning how to formulate and answer specific questions with careful and creative thinking.

The real point of my comment was not categorizing women as ‘feminine’ or ‘unfeminine’, that seems to be the concern of some women, but not me. The real point was categorzing women as either uninterested in science, or interested in science — which if our real goal is the latter of the too, then based on my experience teaching, we have to do a better job of reaching the women that more apt to wear lipstick. The lipstick-toting female has the potential to be our future scientists along with the non-lipstick toters, they just don’t seem as motivated to move into the field. So if a video can make science seem more accessible to them, that is fine with me, if the end result is expanding the base of women interested in science.