Title: Resolving Dark Matter Subhalos With Future Sub-GeV Gamma-Ray Telescopes

Authors: Ti-Lin Chou, Dimitrios Tanoglidis, and Dan Hooper

First Author’s Institution: Dept. of Physics, University of Chicago, USA

Status: Submitted to the Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics (open access)

We are surrounded by undetected dark matter. In fact, our entire Galaxy is enveloped in a large halo of it, but because dark matter does not emit or reflect light, the halo is completely invisible. Inside this halo, orbiting our galaxy, are hundreds of smaller, equally invisible dark matter halos (Figure 1). The larger ones contain their own dwarf galaxies, but the smallest halos are so tiny that they contain no stars at all. However, if the leading theory of WIMP (Weakly Interacting Massive Particle) dark matter is correct, there is one way that we could actually see these dark matter halos without the help of any stars. If dark matter particles are their own antiparticle, they would annihilate when they come into contact with each other, producing various particles, including highly energetic photons known as gamma-rays.

Figure 1. Galaxies like the Milky Way are surrounded by small dark matter halos (blue blobs). Some of these halos contain no stars, but could still produce gamma-rays from dark matter annihilation! Source: ESO

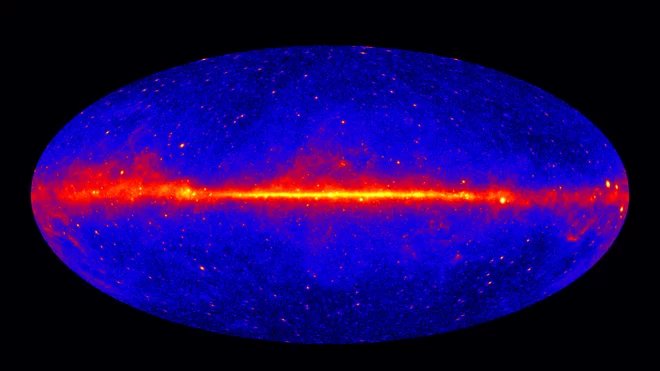

Gamma-rays have millions of times more energy than the optical photons that human eyes can see, yet these energetic particles are quite difficult to detect. The current leader in gamma-ray detection is the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, a satellite that has been orbiting the Earth, searching the sky for gamma-rays, for almost 10 years. Since Fermi was first launched, scientists have searched the gamma-ray sky for evidence of dark matter annihilation. What makes this search really tricky is that dark matter is not the only thing that produces gamma-rays. The sky is actually full of gamma-rays coming from all directions, produced by clouds of gas, pulsars, and active galactic nuclei, among many other sources (Figure 2). However, those tiny dark matter halos that don’t contain stars or gas or any kind of non-dark matter should only be producing gamma-rays from dark matter annihilation. The catch is that we have no idea where these dark matter halos are. Scientists, therefore, have searched all across the sky for gamma-rays that might be coming from dark halos, and they just might have found a couple.

Figure 2. The sky as seen by Fermi is full of gamma-rays. The central band of the Milky Way is clear in this image, as it produces a huge number of gamma-rays. Away from the Milky Way it is easier to spot individual objects, some of which could be dark matter halos! Source: NASA

Two sources of gamma-rays fit all the requirements – they are in the right part of the sky, do not emit any other kind of light (as you’d expect from a halo containing only dark matter), and appear to extend wider across the sky than the single point of a far away star. However, it’s impossible to tell whether these sources are really extended like a dark matter halo or whether they are just two star-like points so close to each other that they blur together, appearing to Fermi as a single blob. Today’s paper considers whether a proposed successor to Fermi called e-ASTROGAM (Figure 3) will be able to resolve the mystery of these gamma-ray blobs. Are they in fact dark matter halos (in which case this would be the first confirmed detection of dark matter annihilation!) or are they simply two points blurred into one?

Figure 3. A model of e-Astrogam, one potential successor to the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope. Source: ESA

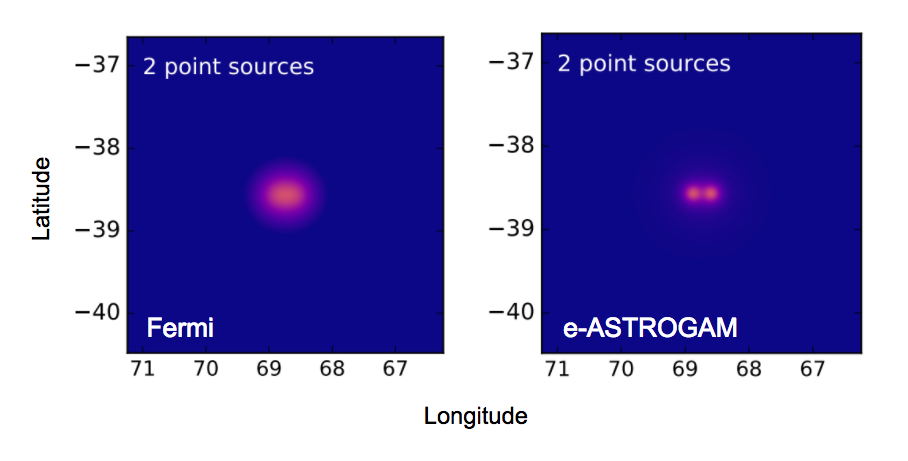

e-ASTROGAM would be quite similar to Fermi, but with several important changes. The biggest difference is that it would be able to detect gamma-rays at a slightly lower energy than Fermi, giving us a brand new view of the gamma-ray sky. In the context of today’s paper, however, the most significant difference is the angular resolution. Angular resolution determines how close together two objects can get before they blur together into a single blob. The angular resolution of e-ASTROGAM will be about 4-6 times better than Fermi’s in the energy range of these mysterious gamma-ray sources. According to the authors of today’s paper, this should definitely be enough to tell whether they are single extended objects or two independent points that are just too close together for Fermi to see (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Simulated images of two point sources as seen by Fermi and e-ASTROGAM. On the left, Fermi is unable to distinguish between the two objects, seeing only a single blob of gamma-rays. On the right, e-ASTROGAM, with its superior angular resolution, can tell that the single blob is actually two individual objects. Source: Figure 3 of the paper.

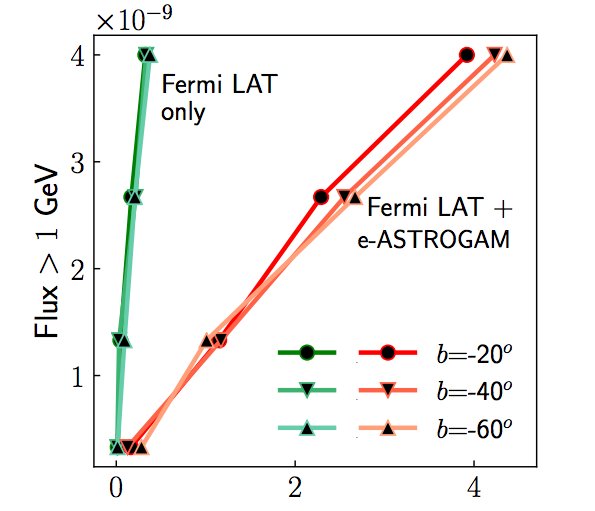

In order to see just how well e-ASTROGAM will be able to see these objects, the authors modeled fake observations of dark matter annihilation from an extended halo and from two point sources. They determined for different halo sizes and dark matter particles how well e-ASTROGAM will be able to tell whether an object is one extended source or two points. Figure 5 illustrates the difference e-ASTROGAM will make in confirming the nature of these gamma-ray sources. The green and red lines represent how easily Fermi and e-ASTROGAM can distinguish pairs of sources (x-axis) as a function of source brightness (y-axis). e-ASTROGAM reaches much farther along the x-axis, indicating that it can much more easily resolve two point sources. The precise numbers change for different dark matter halos and particles, but in all cases e-ASTROGAM shows a significant improvement over Fermi.

Figure 5. This plot illustrates how e-ASTROGAM will be able to help distinguish between extended dark matter halos and two nearby points. The y-axis shows how bright the object in question is, and the x-axis is related to how easily the telescope can distinguish between two nearby points and a single extended object. Even with really bright objects Fermi (green) has a hard time distinguishing between the two scenarios, while e-ASTROGAM (red) can more easily tell the difference. Source: Figure 5 of the paper.

A future gamma-ray telescope like e-ASTROGAM will be an essential tool in determining whether Fermi has in fact detected dark matter annihilation from dark halos. In addition to determining whether the two potential halos detected by Fermi are actually just pairs of close-together point sources, e-ASTROGAM may be able to detect gamma-rays from even more dark matter halos that are too faint for Fermi to observe on its own. e-ASTROGAM with its superior angular resolution and lower energy range would provide a brand new view of the gamma-ray universe, giving us unexpected insight into known and unknown sources of gamma-rays, and perhaps finally revealing the nature of dark matter.

Thank you for the effort of this excellent summary. If dark matter would indeed emit gamma rays, what would a signal of dark matter annihilation look like (for example comparing it to the GRBs of super / hypernovas)?

Hi Christian – Unlike GRBs, which only last for a short time, we would expect most dark matter annihilation signals to be constant over time. We expect to observe these signals in areas with a high density of dark matter where particles would be continuously annihilating. The exact nature of the signal depends on the particular dark matter model, but we can make predictions for different models of how the signal should depend on gamma-ray energy. The predicted signals for the most popular dark matter models look most similar to the gamma-ray signals coming from pulsars, so one of the biggest difficulties in confirming detections of dark matter annihilation is making sure that we are not actually seeing pulsars. Thanks for the comment! -Nora