Title: K2-NnnA b: A Binary System In The Hyades Cluster Hosting A Neptune-Sized Planet

Authors: David R. Ciardi, Ian J. M. Crossfield, Adina D. Feinstein et al.

Lead Author’s Institution: Caltech/IPAC-NASA Exoplanet Science Institute Pasadena, CA USA

Status: Submitted to AAS Journals [open access]

The authors of today’s paper report the discovery of a Neptune-sized planet in the nearby Hyades Cluster around a binary star. A binary is just two stars mutually orbiting their center of gravity; the larger star is called the primary and the smaller is the secondary. In a close binary where the stars are separated only by a short distance, the two stars affect the evolution and size of each other. Planets in binaries have to survive in an extreme environment for an incredibly long time. This binary system is referred to as EPIC 247589423 (also called LP 358-348), but the primary and secondary stars within this system are called K2-NnnA and K2-NnnB, respectively. Since this planet was discovered orbiting just the primary star, the authors of this paper have decided to refer to it as K2-NnnA b: exoplanets are generally named after their host star and then have another letter added to the end. However, this planet does not yet officially have a name, so there is hope that it will be called something that rolls off the tongue a bit more easily.

Significance to Planetary Formation and Evolution

Planets in binaries must form under the influence of two stars, which is an extreme environment, particularly if the two stars are close. The system EPIC 247589423 has a very close separation of 40 AU, which is roughly the distance from Pluto to the Sun. Using out system as an example, if we replaced Pluto with another star, it is easy to see that the rotation and generally everything about the planets would be drastically affected. By studying planets in these environments, we can learn the extremes of planet formation.

These extreme planets test the robustness of planet formation, since these have to survive in an extreme environment for a long time. These also test how often planets are retained by their host star rather than destroyed by the changing gravitational field. By finding and studying planets in clusters, we may begin to understand how planetary systems form and evolve and find out the timescale for such events.

K2 and Follow-up Observations

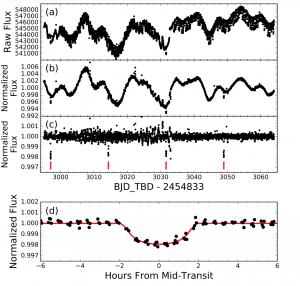

K2, or as I like to call it, Zombie Kepler, is the current mission for the Kepler Space Telescope. The Kepler Space Telescope was launched in 2009 with the mission of finding exoplanets through transit photometry. The method of transit photometry means recording the brightness of the star for an extended period of time, then looking for any small periodic ‘dips’ in this where an exoplanet eclipsed a small part of the star. This data is generally referred to as a light curve, since there is a rounded dip where the exoplanet eclipses the star. After a mechanical mishap in 2013 with the Kepler Space Telescope, the scientists working on this mission still found a way to use the telescope to look for transiting exoplanets. Instead of observing one single part of the sky for an extended period of time as before, K2 now observes smaller patches of the sky for shorter amounts of time. Figure 1 shows several stages of the light curve analysis from K2.

Figure 1: This shows the light curve in various stages of analysis from K2. The topmost panel shows the light curve with the telescope rotation removed. The second panel shows the binned version of the top panel. The third shows the data with the stellar variability removed, and the lowest panel shows the folded and binned result for the planet transit.

These scientists used the K2 data to discover this short period exoplanet by looking at the starEPIC 247589423. Since this planet is in a binary system, the researchers had to first remove the stellar variability inherent in the data. The two stars within the binary already eclipse each other and cause dips in the light curve, which can make it difficult to find a much smaller dip from the planet. After removing the eclipse variability, they found the planet and solved for the period and radius of K2-NnnA b.

After the initial discovery with K2, the researchers followed up their discovery with new observations and archival data to confirm their discovery. They used the archival data from 1950 Palomar Observatory Sky Survey to rule out any other object that could be causing the dip in the light curve. For example, if another eclipsing binary was behind this system, the variation in that system could be mistaken for a planet. However, by analyzing the data, these researcher ruled out those possibilities, then made observations using the Keck I telescope.

K2-nnnA b: Planet Properties

K2-NnnA and K2-NnnB make up a binary system in the nearby Hyades cluster. They are separated by about 40 AU. The planet orbits the K2-NnnA with a period of 17.3, and its transit lasts roughly of 3 hours.

K2-NnnA b is one of the first Neptune-sized planets that has been observed orbiting in a binary system within an open cluster. This cluster, the Hyades, is the nearest star cluster to the Sun and is roughly 750 Myr old. The discovery of this planet can provide us with a better understanding of the planet population in stellar clusters and allow us to place more limits on planetary formation and evolution.

The authors of this paper say planets discovered in nearby star clusters ‘provide snapshots in time and represent the first steps in mapping out [planetary] evolution,’ and I wholeheartedly agree. The discovery of K2-NnnA b brings with it new understanding of planet formation in star clusters and in binary systems. The possibilities of planet formation and evolution are certainly not limitless, and with more and more discoveries like K2-NnnA b, we can hopefully find the extremes of planetary systems.

Hi, enjoyed your article. Just wanted to mention this paper which was published on the same day, where they identify 3 planets in the same system!

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1709.10328.pdf

“K2, or as I like to call it, Zombie Kepler”, not nice, unnecessary, beneath dignity, demeaning. K2 Kepler is doing great work. I hope that the writer, Mara Zimmerman , is as successful as Kepler, even as K2.

Richard,, keplar died and was brouht back to live with k2 so zombie

I agree! The moniker “vampire Kepler” is much more dignified, and pays proper homage to the legacy of Bram Stoker that inspired the creation of this noble, space-faring member of the living dead. To call this bloodsucking telescope a “zombie” is an unforgivable insult to Vampire Kepler, and undead telescopes everywhere! I doubt Ms. Zimmerman should fare so well when fired into deep space for eight years.