This post continues our series on interactions between predominantly-western astronomy and Indigenous communities around the world. Other posts in the series: Hawai`i.

North America has a long history of settler-colonialism and of forcibly removing Indigenous communities from their native lands. Nearly all academic and astronomical institutions in Canada, the United States, and Mexico are therefore situated on stolen land. This history is extensive and well beyond the scope of this Astrobite, but here are a few places you can start reading more about it: here and here.

In today’s Astrobite, we’ll focus on two case studies of interactions between astronomers and Indigenous communities in the southwest US.

“A Simple Matter”? The Tohono O’odham People and Kitt Peak National Observatory

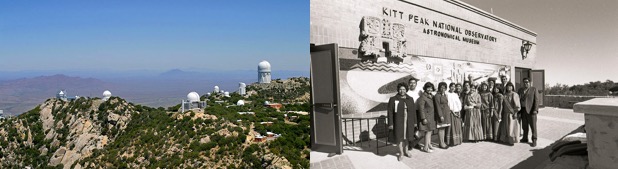

Left: Kitt Peak National Observatory. (NOAO/AURA/NSF) Right: “Visit of Miss Indian America and Miss Papago to Kitt Peak.” (NOAO/AURA/NSF)

The first national optical observatory in the US, Kitt Peak National Observatory (KPNO), is maintained on land in southern Arizona leased to the US National Science Foundation (NSF) from the Tohono O’odham Nation. Previously known as the Papago Tribe, the Tohono O’odham Nation is a federally-recognized sovereign nation; today, it has nearly 30,000 tribal members.

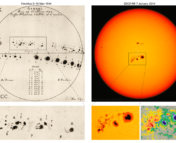

When astronomers began surveying the US for an observatory site in the 1950s, Kitt Peak’s weather, visibility, and distance from nearby cities made it stand out as an ideal site for astronomy. However, shortly after its location was chosen, the selection team realized it was on Tohono O’odham land. In 1956, the Tohono O’odham Nation granted permission for astronomers to summit Kitt Peak, while O’odham guides explained its significance: Kitt Peak is held sacred by the Tohono O’odham, who call the mountain “Iolkam Du’ag” and consider it to be the garden of I’itoi the creator (source).

Members of the astronomical community met with elders and members of the Tohono O’odham Nation government, including council members from the Schuk Toak District where Kitt Peak is located. These meetings included bringing the tribal council to look through a 36-inch telescope at the University of Arizona. “We showed them things like the moon and how the telescope made the images much larger and showed details as well as galaxies and planets,” said astronomer Helmut Abt. Shortly after this, the Tohono O’odham agreed to lease 200 acres of land in perpetuity to the NSF, and KPNO was formally founded in 1958.

The precise details of how this agreement came about are obscure. Many scientists claim that obtaining the lease approval was “a simple matter,” as astronomer Frank Edmondson put it, but it may have been a more complicated process. The Tohono O’odham District Council rejected two early drafts of the lease, and there were discussions about specifically prohibiting tribal outsiders from entering sacred caves near the summit (though these terms did not appear in the final draft of the lease). Furthermore, multiple analyses later showed that O’odham opinions were likely more divided than astronomers’ narratives suggest, and that financial incentives may have played a strong role (Swanner 2013: 446-448).

This alternate narrative became more evident in 2005, when the Tohono O’odham Nation filed a lawsuit against the NSF. The lawsuit claimed that the NSF had violated the National Historic Preservation Act by not consulting with the tribe and the Arizona Historic Preservation Office before beginning construction on the Very Energetic Radiation Imaging Telescope Array System (VERITAS), a proposed gamma ray detector. The lawsuit further pushed to completely revoke the NSF’s lease, claiming that the tribe’s interests had not been fairly represented when the lease was initially agreed upon (Swanner 2015: 151-152). VERITAS was eventually relocated to another mountain.

Today, the KPNO lease remains. KPNO has since made efforts to remain on good terms with the Tohono O’odham Nation: the Observatory preferentially hires O’odham staff and hosts educational outreach programs specifically for the Tohono O’odham Nation, and the KPNO Visitor Center sells Tohono O’odham crafts along with astronomy merchandise. But the 2005 lawsuit suggests that these relations cannot be dismissed as “a simple matter,” and the process by which KPNO gained land use rights in the first place was more contentious than many astronomers believe.

“A Sacred Character”: The San Carlos Apache Nation and Mt. Graham International Observatory

Left: Ola Cassadore Davis, the founder of the Apache Survival Coalition. (Photo: Robin Silver) Right: The Large Binocular Telescope at MGIO. (NOAO/AURA/NSF)

Other observatories on mainland North America—even within the same region—have had very different interactions with Indigenous communities. Mount Graham International Observatory (MGIO) is run by Steward Observatory, the research arm of the University of Arizona’s Department of Astronomy. Mt. Graham, located in the Sonoran Desert in southern Arizona, is today part of the Coronado National Forest.

In 1984, astronomers from the University of Arizona and other research institutions proposed building the world’s biggest telescope on Mt. Graham. Mt. Graham was removed from the San Carlos Apache reservation in 1873 by the US government and became public land (Swanner 2013: 361). As a result, despite the mountain’s location on traditional Apache lands, MGIO was not required under US law to conduct formal negotiations with the San Carlos Apache Nation.

Instead, immediate opposition to MGIO came from environmental groups, who pointed out that the only known habitat of an endangered species–the Mt. Graham Red Squirrel–was near the summit of the mountain. Contentious public debate kept the project at a standstill, until the US Congress passed a legislative rider in 1988 (Title VI of this law) compelling the US Forest Service to allow three telescopes to be built on Mt. Graham. This set off a protracted legal battle from 1989-1994 (see final court decisions here, here, and here). But in the midst of the conflict between MGIO and environmentalists, a new faction began to speak up: the San Carlos Apache Nation, who consider Mt. Graham (known as “dził nchaa si’an”) sacred. According to Apache elders, the mountain is home to spirit dancers who also assumed human form, as well as “holy water […] and sacred herbs and a burial site” (Swanner 2013: 324-325).

This was not the first time cultural preservation had been an issue for the MGIO. During the public conflicts in the 1980s, two shrines had been discovered on one of Mt. Graham’s peaks. In response to this, the University of Arizona sent form letters to nineteen federally-recognized tribes in the area. However, the San Carlos Apache tribe did not respond–later, the Tribal Chairman denied ever receiving the letter, and the Tribal Council formally submitted that any letter would not have constituted a proper “investigation or a consultation” (Swanner 2013: 367). Furthermore, silence as a response can itself have important social connotations in Apache culture, and many anthropologists have noted that Apaches are generally unwilling to divulge traditional religious customs with outsiders.

It wasn’t until 1990 that tribal elders founded a non-profit organization, the Apache Survival Coalition (ASC), specifically to oppose the MGIO. The ASC appealed to the San Carlos Apache Tribal Council to pass an official Resolution opposing telescopes on Mt. Graham, and other tribes (including the Tohono O’odham) passed supporting resolutions (Swanner 2013: 386). In 1991, the ASC filed a lawsuit against the Forest Service, claiming that the Forest Service had violated the National Historic Preservation Act. As delays and financial restrictions piled up, partners began to pull out of the MGIO collaboration; the Ohio State University withdrew support for the awkwardly-named “Columbus” telescope, and the Smithsonian Institution decided to instead site their Submillimeter Array on Maunakea in Hawai`i.

The issue of sacred land was further complicated by the involvement of one of the remaining MGIO partner institutions—the Vatican Observatory, which now operates the Vatican Advanced Technology Telescope (VATT, but known colloquially as the “Pope Scope”) at MGIO. In 1987, Pope John Paul II visited Arizona and urged native people to “preserve and keep alive your cultures, your languages, the values and customs which have served you well in the past and which provide a solid foundation for the future.” Yet in response to the ASC’s claims of sacred land, Father George Coyne (a Jesuit astronomer who was the director of the Vatican Observatory) wrote, “We are not convinced by any of the arguments thus far presented that Mt. Graham possesses such a sacred character which precludes responsible and legitimate use of the land” (Swanner 2015: 157).

These remarks, echoed by other astronomers and Jesuit priests, outraged many members of the San Carlos Apache Nation and other Native American communities, who saw this as a colonialist denial of the validity of Indigenous culture. This in turn intensified political divisions among the San Carlos Apaches, some of whom supported building telescopes and believed that the Tribal Council should not have spent resources on the ASC lawsuit.

Yet opposition to MGIO remained strong, even after construction at MGIO finally started in 1989 and the ASC lawsuit was dismissed in 1992. On the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ arrival to the Americas, a group of over 200 people stormed Steward Observatory to protest telescopes on Mt. Graham. Construction on the Large Binocular Telescope (which was originally called the “Columbus” telescope) was slated to begin in 1993, but was delayed for years due to several lawsuits from the ASC and environmental groups. Eventually, a second Congressional rider in 1996 (Sec. 335 of this law) was required to allow construction to begin, and even then the telescope wasn’t fully finished until 2003 due to lack of funding.

Today, MGIO hosts only 3 of the 13 telescopes originally planned by Steward Observatory. Relations between the astronomical community and other factions in the community remain strained. Although the Observatory runs summer programs for San Carlos high school students, the “History” page on the official MGIO website does not contain any information about the Apaches, and MGIO’s Discovery Park only directly references the Apaches in a small exhibit displaying multiple creation myths from around the world. The decades-long contentious history between MGIO and Indigenous communities is now largely glossed over by much of the astronomical community.

Takeaways

Kitt Peak National Observatory and Mt. Graham International Observatory are just two examples of how western astronomers have interacted with Indigenous communities. It’s clear that for both observatories, these interactions and their outcomes were partially shaped by broader social, historical, and cultural contexts. It’s crucial—perhaps more now than ever before—for astronomers to understand these ever-changing contexts.

KPNO and MGIO illustrate how astronomical endeavors affect the rest of society. Our community is not inherently better or worse than any other community, our own history is neither objective nor rational, and it’s not until we reckon with this that we can begin learning how to move forward.

Stay tuned for future Astrobites discussing how predominantly-western astronomers have interacted with Indigenous communities in other regions of the world.

This article was prepared with the help of several Astrobites authors.

Correction: The original version of this article mistakenly reported that “the terms of the lease [between the Tohono O’odham and KPNO] specifically [prohibited] tribal outsiders from entering sacred caves near the summit.” The lease does not explicitly mention these caves, and the article has been amended to reflect this.

Memorializing the indigenous cultures and traditions by campuses of shrines and temples incorporating the observatories could be to the advantage of both parties.