February is Black History Month in the United States. For this month and beyond, we wish to continue highlighting the important work and achievements of Black astronomers, physicists, educators, and scientists through our #BlackInAstro series. This is an ongoing, year-round series in collaboration with blackinastro.com (@BlackInAstro on Twitter). For our cornerstone post, see here.

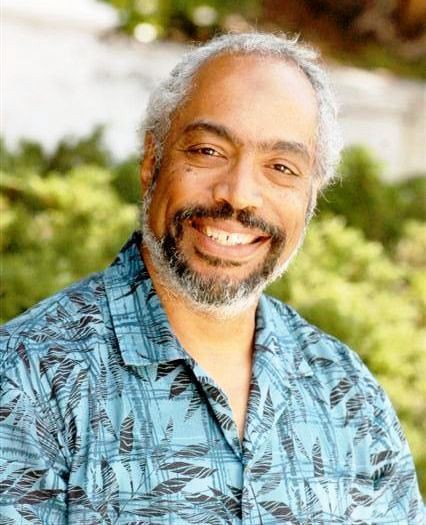

Dr. Gibor Basri is a pioneer in the field of stellar astronomy, having made significant advancements through his work on stellar magnetic activity, stellar atmospheres, and stellar rotation. On top of all this, he has committed a significant portion of his career to supporting underrepresented minorities in the sciences, most notably through his position as the founding Vice Chancellor for Equity and Inclusion at UC Berkeley, where he currently holds an emeritus professorship. While it would take most of this article to list his noteworthy accomplishments, a unifying thread that has defined his career and really, much of his life, is an undying passion for science. As he puts it, “science is the only community [he’s] felt truly a part of,” and it is this sense of belonging that has kept him “motivated to try to stay in [the field],” despite the shortcomings he has seen.

From a young age, Dr. Basri knew that he was very interested in – and academically good at – the sciences. Growing up during the Apollo era with a healthy love for science fiction, this interest manifested itself in astronomy. However, despite his excitement about the field, he was always cautiously optimistic, recognizing that it was tough to have an astronomy career, due to the limited number of positions available. His father, a physics professor at Colorado State University, encouraged him to pursue his passion while keeping his options open. Accordingly, he completed his undergraduate degree at Stanford University in physics, rather than astronomy. While studying, however, he realized that he really only found physics exciting in its application to astronomy, so, once he graduated, he decided to pursue a PhD degree in astronomy at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

When reflecting on his childhood in the predominantly-white Fort Collins area in Colorado, Dr. Basri identified a silver lining to what was otherwise a fairly isolating experience: he found that being the only Black student in his school (and, at some level, his whole town) meant that, from a young age, “[he] developed internal and external methodologies of navigating a world in which [he] was the only person who looked like [him]”. In this regard, in his undergraduate and graduate career, he felt that it was maybe easier for him to navigate predominantly white academic spaces than for some of his Black peers, who had grown up in communities surrounded by other Black folks. As he puts it, “if you’re not really used to that [feeling of isolation], it’s disturbing on a subliminal level, even if it’s not disturbing consciously.” This helped him navigate an otherwise potentially isolating culture and allowed him to focus on his true passion: his science.

During his PhD, he began his work on stellar magnetic activity and upon graduating, he credits his advisor’s “tough love” with ultimately helping him advance to success. Recognizing his talent as a scientist, his advisor refused to take him on in a post-doctoral capacity and instead insisted that he pursue a faculty position at a larger university. This led to the then-newly minted Dr. Basri quite literally walking into a Berkeley faculty member’s office uninvited and walking out with a job as a postdoc. This post-doctoral position opened a path to professorship for him and shortly afterwards, he became a professor at Berkeley. At this point, while he did have to contend with the experience of being either the only or the other Black faculty member in all the physical sciences, he felt that amongst his peers, he was judged by his science more than anything else. Despite “always [feeling] like [he] was an outsider” in many facets of his life, “once [he] was a grad student and doing science successfully, people evaluated [his] work on its own merit,” so science was really the only place he truly felt at home.

Throughout the earlier stages of his career, Dr. Basri’s primary focus was research. He is a firm believer that, when it comes to diversity efforts, the most significant change comes from the top. Therefore, one ought to focus on advancing their career to the point at which they can effect real, lasting change in the field. His advice to young scientists passionate about diversity efforts is, “… don’t worry about that too much right now. Worry about getting your degree, then worry about getting a faculty position, then worry about getting tenure, then worry about [addressing systemic issues in the field]. If you don’t worry about those things first, then you won’t be in the same position of power to do bigger and better things later.” As such, it was not until he had established himself as a faculty member at Berkeley that he began to dedicate significant time to equitable education efforts within the university beyond the level of student programs and mentoring, which he had always done. Starting out as a member of the faculty senate and eventually leading its Committee on Diversity and Equity, he found that he finally had a voice in advocating for meaningful change in the university’s culture. Prior to his efforts, faculty would be penalized for dedicating time towards diversity efforts (because it was seen as detracting from their research), so he helped push forward a UC-wide amendment to the faculty personnel manual to give credit to faculty for this work at the same level as their scientific work. In his position as Vice Chancellor, he led data-driven advocacy efforts – both within Berkeley and on a UC-wide scale – to push for representation and diversity at the highest levels, spearheading initiatives to gather numbers on these previously-unstudied topics. As he says, “people were not expecting the first Vice Chancellor for Equity and Inclusion to be a scientist” – he made use of his scientific training to collect data and raise evidence-based awareness of fundamental issues in campus climate and diversity.

Throughout all of this identity-based work, Dr. Basri’s commitment to astronomy stayed its course. In addition to his accomplishments for diversity, he served as a co-investigator on the Kepler mission, making advancements in our understanding of stellar variability and starspots. The Kepler space telescope observed nearly 200,000 stellar light curves and, from these, detections of thousands of transiting Earth-sized extrasolar planets were made. Robust analysis of these light curves, however, requires a solid understanding of the effects of starspots and other stellar activity, so Dr. Basri’s work was pivotal in this regard. Prior to this point and over the course of his career, he had already contributed to a number of different subdisciplines in stellar astronomy. He started out with work on star formation and protoplanetary disks, making seminal discoveries concerning the structure and effects of magnetic fields in young stars. He also made use of high-resolution spectroscopy from the Keck telescope to study low mass stars. He extended this to brown dwarfs after becoming one of their original discoverers (which he sees as a highlight of his career). Most recently, he authored a textbook that provides a comprehensive review of the field of stellar magnetic activity. Suffice to say, Dr. Basri has made – and continues to make – a slew of fundamental contributions to this field.

Looking ahead, Dr. Basri envisions the ideal academic environment for Black folks and other underrepresented minorities as one with simply more representation. One of the biggest obstacles for anyone getting involved in science research is “that you can’t see yourself doing it or don’t know anyone who does it,” so representation is pivotal for young scientists to believe that they can succeed in such a field. In addition, he describes how new perspectives and cultural shifts are concomitant with the addition of fresh new faces and ideas, and believes that more faces in science would help change things for the better. As Dr. Basri puts it, “we need more role models” in the sciences and, after chatting with him, I have no doubt that he has been just that for countless students in his career.

Author’s Note: When approaching Dr. Basri for this interview, having read about his accomplishments and various active projects, I envisioned us having a tough time coordinating our schedules and finding the time to chat. I couldn’t have been more wrong. I reached out to Dr. Basri on a Friday afternoon, he responded on Saturday, and by Sunday afternoon, we had a time set up to meet on Monday. Having dealt with the busy schedules and delayed responses that communication with science faculty can often bring, I felt that this was a real testament to his commitment to diversity and engagement with students. This, coupled with his friendly disposition and his general excitement around the conversation, made his passion for science and diversity almost contagious.

To learn more about Dr. Basri, check out his website!

Astrobite edited by Wei Yan and Pratik Gandhi

Featured image credit: Astrobites collaboration

Thank you for this enlightening series! All respect to Dr. Basri and his journey.