Title: The Astropy Problem

Authors: Demitri Muna et al.

First author’s institution: Center for Cosmology and AstroParticle Physics and Department of Astronomy, The Ohio State University, USA

Status: available on arXiv

Today is one of those occasional Fridays we will go beyond Astrobites’ usual subjects. This time we are remaining within the astro-ph boundaries; however, today’s paper is not about science itself, rather about the tools we use for doing it. More specifically, about the recognition and importance we (don’t) give to those behind such tools. Today’s paper focuses on Astropy, a core package for Astronomy in the programming language Python widely used by our community. The problems faced by the Astropy Collaboration that are raised in this paper extend to anyone involved in software development for Astronomy, and arguably science in general.

A Brief History of Astropy

If you have ever written a Python code to help you with a task in Astronomy, there’s a good chance it starts with “import astropy”. You’ve probably also read papers in which Astropy is used to process and analyze data. If you happen to have any of those laying around, quickly check something: do the authors cite Astropy Collaboration et al. (2013)? If the answer is no, this is probably not the only case. Said paper has only about 400 citations, which clearly does not reflect its importance to our community. Even if you don’t write any code, you’ve probably come across data that was either collected, reduced, or analyzed by code that uses Astropy.

Astropy is older than you’d think. The foundations for it began in 1998 at the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI). IDL was the most popular programming language in Astronomy at the time, but it was subjected to a license fee. STScI was the first to point out the potential a move from IDL to a modern, free programming language such as Python would offer. At the time, all development was in direct support of the STScI mission; any generalization to other telescopes had to be additionally argued for. In the early 2000’s, this move to Python was something that was spreading more generally in the community. Many people no longer had patience with some of the existing, outdated tools; Python represented a modern alternative.

This move was not an organized effort at first. Many people were doing it at the same time and independently. At one point, Erik Tollerud, a graduate student at UC Irvine at the time, realized there were fourteen independent Python packages to perform coordinate system transformations. This called attention to the need for a coordinated development effort, which in 2011 lead to the Astropy project. It incorporated much of the software developed by STScI cited above, with some additional functionality. Nowadays it includes handling coordinate systems, times and dates, modeling, FITS, ASCII, and VO file access, cosmological calculations, data visualization, and much, much more. In short, it’s an awesome tool for the everyday needs of an astronomer.

The problem: who’s paying for all that?

If Astropy is so awesome, of course it gets good funding, right? Wrong. It gets none. Except for the initial efforts at STScI, nobody else got paid for their work in Astropy. The development is led by graduate students and postdocs, with some contributions from undergrads and faculty members, in their spare time. This complete lack of funding of something that is nowadays so essential to our community, plus the little recognition in form of citations, is something that shouldn’t be overlooked. Today’s paper intends to raise the issue, and proposes some potential solutions.

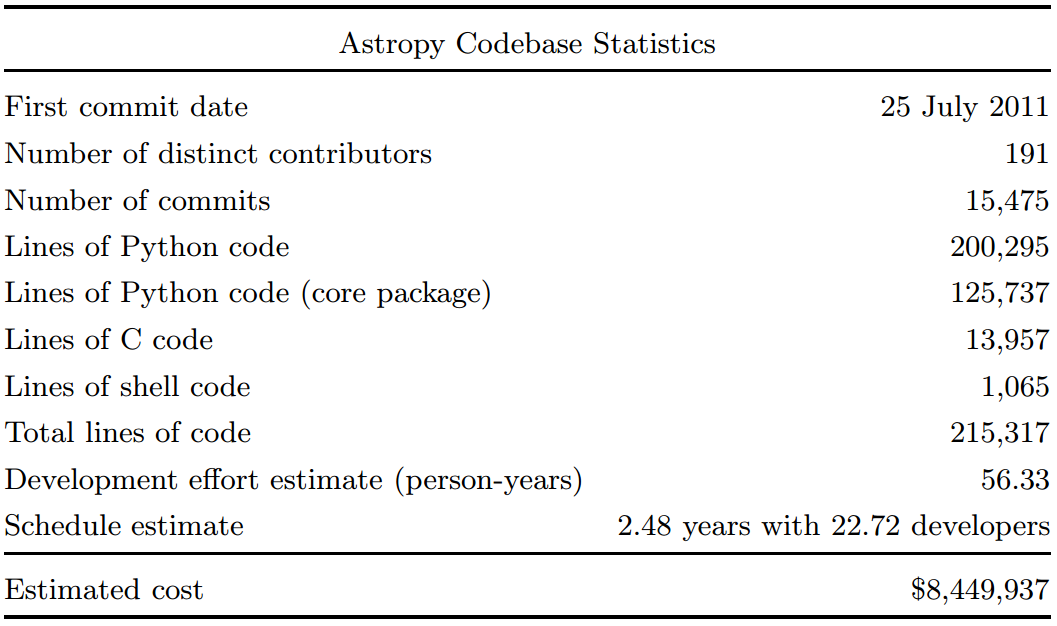

But who should be paying? Employees of NASA say their money has to go to specific projects; it cannot be spent for general software. Academic institution members state that their primary mission is education, so they cannot fund software development. Other scientific institutions argue that their responsibility is to operate and run the telescope and data archives already under their remit. Finally, individual surveys received money to deliver data, not to develop software for the community. These negative opinions are widespread in Astronomy. In short, our community as a whole appears to have decided that Astropy and general software development is not something worth funding. Nonetheless, we all depend critically on it, in one way or another. And it is not cheap, as you can see from Table 1. How crazy is that?

Moreover, people not only use Astropy as is, there’s also an expectation that it will continue to be developed, have more features added, bugs fixed, and so on. We sort of think that software is something that just “happens”, the authors say, and therefore expect it to be free. However, the developers do pay a cost by investing their time, at the expense of their research and their publication output. Yet, their efforts at Astropy are usually not considered by hiring committees.

Table 1: Some statistics for Astropy based on the repository as of July 2016, version v1.2. All repositories under their GitHub account have been included, but external C libraries (namely cfitsio, ERFA, expat, and wcslib) have been excluded. The cost and development were estimated using David A. Wheeler’s SLOCCount software.

Possible Solutions

The authors point out that funding should be made available not only to support today’s software, but also what we’ll need in the future. We should create career positions that offer stability and good salaries to people willing to do software development. Some paths to this state of affairs are suggested by the authors. One is a subscription fee to Astropy. Institutions would pay a fee on a volunteer basis, whose value could be based perhaps on the number of users. This would not require a license server or restrictions to the use of the code, or actually alter the way Astropy is currently distributed, it would merely be a form to collectively cover its costs.

Another option is the creation of full-time developer positions within existing projects, and future ones, once they reach a certain level of funding, say $40M for example, which is the approximate cost of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. The idea is that any project with funding above that should hire a developer to work within and be hosted by the survey/mission, serving as a liaison with Astropy. They would of course work on code that would directly benefit the mission, but keep in mind that it must be adapted for use by the general community.

These are only some of the ways to overcome the so-called “Astropy problem”, but serve to show that there are easy solutions to this problem. Our community should be considering them. As it is now, we receive and even expect enormous utility from the developers of scientific software without support, compensation, career paths and even recognition. It is common knowledge that we lack the tools necessary to comprehensively analyze the sheer amount of data available today, so we clearly need people willing to work on software that will allow us to do it. It’s reasonable that the community starts rewarding these efforts, as well as respects, encourages, and enables it. What are your thoughts? Do you have more suggestions to fix the problem? Let us know in the comments!

Note: The paper discussed here is not an official paper of nor officially endorsed by the Astropy Project, rather it is a reflection of the opinions of the authors.

Nice article, Ingrid. I also feel more directly recognition and support should be given to those who better the tools we use for science.