Welcome to the summer American Astronomical Society (AAS) meeting, held virtually for the first time! Astrobites is attending the conference as usual, and we will report highlights from each day here. If you’d like to see more timely updates during the day, we encourage you to search the #aas236 hashtag on twitter. We’ll be posting once a day during the meeting, so be sure to visit the site often to catch all the news!

Solar Physics Division (SPD) Hale Prize Lecture: From Jets to Superflares: Extraordinary Activity of Magnetized Plasmas in the Universe (by Abby Waggoner)

The last day of AAS 236 started off with the Solar Physics Division Hale Prize Lecture by Kazunari Shibata from Kyoto University. Dr. Shibata was awarded the Hale prize for his years of research on magnetized solar and astrophysical plasma and the discovery of solar jets. Dr. Shibata is the first scientist from Japan to receive the Hale prize, which is the most prestigious award in solar physics.

Dr. Shibata didn’t always study solar physics. During his graduate studies (1973–1977) he sought to solve the “biggest puzzle in astrophysics”: the jets produced by active galactic nuclei (AGN). A series of jets were discovered in the 1960s, but the physics behind them was unknown at the time. AGN are difficult to observe directly, as they are billions of light-years away from Earth, so Dr. Shibata approached the problem from the theory side by studying magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) plasma. When the first protostellar jets were discovered, Dr. Shibata noticed that the morphologies of protostellar jets and AGN jets were similar, thus indicating that the jets were likely driven by the same physics.

What are astrophysical jets like? Here's a quick summary: pic.twitter.com/g0s6s889yq

— astrobites (@astrobites) June 3, 2020

At this point in time, scientists understood that jets in AGN originated from the transfer of kinetic energy produced by accretion, but the process by which the gravitational energy is converted to kinetic energy was still unknown. Dr. Shibata believed that the magnetic fields on the Sun were the key to understanding this, and he was right! He noticed that the spinning jets on the Sun could be related to the twist of a magnetic field.

The energy of unwinding of field lines can be released into kinetic energy! pic.twitter.com/75GiuvwAS2

— astrobites (@astrobites) June 3, 2020

This relation was confirmed when simultaneous observations in H-alpha and X-ray light were done on a single flare. Solar flare production by magnetic reconnection became known as the standard model. Dr. Shibata was able to connect the standard model to jets produced by AGN. Convection and rotation in the Sun (stellar dynamo) allow for the magnetic reconnection of magnetic field lines on the Sun, while accretion and rotation of the accretion disk around a black hole enables magnetic reconnection in AGN.

In the 1960s, the standard flare model was developed. Below the prominence, we have antiparallel lines that release magnetic energy. pic.twitter.com/yx4TbkrM1T

— astrobites (@astrobites) June 3, 2020

Dr. Shibata concluded his talk by discussing statistics done on the frequency of solar flares and the significance of “super flares.” He found that a super flare (energy range > 1033 erg, which is a lot of energy) could be produced by the Sun once every ~10,000 years. While we’ve never observed a super flare (luckily), he commented that a super flare could possibly be related to the origin and evolution to life on Earth.

(Conclusions continued)

-"Extreme activity (such as superflares) on the Sun may have been related to the origin and evolution of life on Earth, whereas it would be extremely dangerous for our civilization in the future."— astrobites (@astrobites) June 3, 2020

Press Conference: Mysteries of the Milky Way (by Haley Wahl)

Today’s first press conference follows on the heels of yesterday’s conference on the galactic center, and focuses on the broader picture of things.

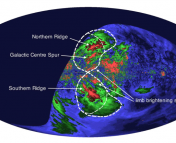

The first speaker today was Dhanesh Krishnarao, a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, speaking on the Fermi bubbles, which are massive lobes that expand out from the center of the galaxy. It’s known that these bubbles absorb light, but Krishnarao and his team discovered that they actually emit light too, and this was all seen by the Wisconsin H-Alpha Mapper, or WHAM! By measuring the optical emission and combining it with the UV absorption data, they were able to conclude that the Fermi bubbles have a high density and pressure. Press release

First discovery of optical light coming from Fermi Bubbles, paper on the ArXiv yesterday (arXiv:2006.00010)! Here's an artist's impression of the bubbles #AAS236 pic.twitter.com/JOZVEwHEe9

— astrobites (@astrobites) June 3, 2020

The next speaker was Dr. Smita Mathur from Ohio State University to discuss a new discovery in the circumgalactic medium of the Milky Way. Before this work, the circumgalactic medium was thought to be mostly warm at temperatures around one million Kelvin. However, Mathur’s team discovered a hot component that’s around ten times as hot. No theory has ever predicted this!

How ubiquitous is that hot component of the circumgalactic medium? Dr. Anjali Gupta from Columbus State Community College, the third speaker of the press conference, explained! Using the Suzaku and Chandra telescopes, the team, led mostly by undergrad student Joshua Kingsbury, found the component in three out of the four sightlines they looked at. This hints at the fact that this hot component of the circumgalactic medium could be present in every direction, but more observations are needed. How can this hot component be explained? It’s possible that it could be related to feedback, from active galactic nuclei and/or from stars (star formation and supernovae)! Press release

The last speaker of the press conference was Dr. Robert Benjamin from the University of Wisconsin, Whitewater, who spoke on a surprising result in a familiar sight in the nighttime sky. Benjamin and his team discovered a thin UV arc shock front whose length in the sky is 30° — that’s 60x the apparent size of the full Moon! If the arc were extended, it would make an enormous circle on the sky with a radius that’s also 30° in size. They believe the arc to be about ~100,000 years old and >600 light-years away and possibly caused by a supernova; if this is the case, it would be the largest supernova remnant in the sky. Press releasePlenary Lecture: Our Dynamic Solar Neighborhood (by Luna Zagorac)

Jacqueline Faherty (American Museum of Natural History) studies our solar neighborhood (20–500 pc from the Sun) because it lets us investigate faint sources in more detail, including brown dwarfs. One important question we can begin to answer in the solar neighborhood is where the high-mass limit of planet formation ends and the low-mass limit of star formation begins. To illustrate what the stellar neighborhood looks like, Dr. Faherty took us on a virtual flight using the OpenSpace software, illustrating the advancement in mapping and astrometry from the Hipparcos data set to Gaia DR2, which mapped more than 1.3 billion sources. Gaia is an optical survey and, as such, is not very sensitive to faint, cold sources like brown dwarfs. When Gaia data was combined with ground-based measurements, however, 5,400 sources were extracted from the sample of Gaia objects within 20 parsecs of the Sun. These sources could then be arranged on a color-magnitude diagram (known as an HR diagram), with brown dwarfs clustering in the lower-left part of the diagram.

Here's these satellites plotted on a color magnitude diagram (an HR diagram)! White dwarfs in the lower left corner. pic.twitter.com/3snO7H8JNn

— astrobites (@astrobites) June 3, 2020

The scatter and differentiations in the diagram give insight into atmospheric characteristics of the colder objects represented. The coldest objects at the end of the spectral sequence, named Y dwarfs, are difficult to find because they’re not very luminous. Their temperatures are around 400 K, and their masses are estimated at ~20 Jupiter masses. These are the very markers of the transition between the bottom of the star formation process to the top of the planet formation process. The best way of identifying these objects has been through citizen science projects — the human eyes are the best recourse we have for identifying brown dwarfs!

Citizen scientists have been searching for these objects by eye through @backyardworlds! pic.twitter.com/OhPZHINKTP

— astrobites (@astrobites) June 3, 2020

Adding the discoveries from the Backyard Worlds citizen science project to the Gaia DR2 20 parsec sample will allow further constraining of brown dwarfs’ mass function. Citizen scientists are also helping to identify co-moving companions to stars, since their mass and separation distribution reveals more information about their formation. This is important because age can determine the mass of the object: “In determining co-moving structures, we can measure their ages and we can use those to do a deeper dive to systems within them,” noted Dr. Faherty. This project is being led by her postdoc, Dr. Daniella Bardalez Gagliuffi.

Furthermore, there are objects in the Tucana-Horologium Association that are in systems where a companion has been discovered right on the mass boundary between planet and brown dwarf formation. These companions resemble Jupiter and have thick clouds, and Dr. Faherty wants to study how their light is changing. To find more of these systems, her former student Dr. Eileen Gonzales is developing BREWSTER, a retrieval code optimized for brown dwarfs, but adaptable to planets as well.

"These companions are at a temperature that's kind of crazy." Here's an example. They look a lot like Jupiter and have thick clouds. We want to look at how their light is changing. pic.twitter.com/9Oz4W4pLwj

— astrobites (@astrobites) June 3, 2020

These data sets have allowed us to better visualize low-luminosity object distributions in the sky, and Dr. Faherty hopes this can be turned into planetarium presentations. She concludes that the multi-dimensional nature of stellar catalogs is highly complemented by visualization tools and that the James Webb Space Telescope will be critical in further characterizing these low-luminosity objects.

OSTP Town Hall with White House Science Advisor Kelvin Droegemeier (by Tarini Konchady)

Note: In the recording of this session, Dr. Droegemeier’s audio for the Q&A was lost. This writeup covers only the topics discussed before the Q&A.

The main speaker at the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) town hall was Director Kelvin Droegemeier. Droegemeier’s scientific background is in meteorology; in 1985 he joined the University of Oklahoma as an assistant professor and has remained at that institution to this day (he has taken a leave of absence to serve as OSTP director). Droegemeier has a long career in federal policy as well, notably serving on the National Science Board from 2004 to 2016. Aside from being OSTP director, Droegemeier is also the Acting Director of the National Science Foundation. He will stay in this role till the Senate confirms the president’s nominee — Sethuraman Panchanathan — for the job.

The Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) Town Hall happening now! Today's speaker is Dr. Kelvin Droegemeier, OSTP Director and Acting NSF Director.#aas236

— astrobites (@astrobites) June 3, 2020

Droegemeier emphasized that his experience as a college professor has informed his work in the federal government. He spoke about two particular OSTP efforts relevant to the AAS: one, helping colleges and universities with “reopening and reinvigorating” after the pandemic, and two, enabling research that would benefit the country.

To the first point, Droegemeier listed various meetings that have been happening between university leadership and federal bodies (including the Vice President and the National Science and Technology Council) as well as guidance issued by the government. He used these examples to emphasize that the government is apparently willing to give institutions leeway if it will allow smoother operations during the pandemic.

Droegemeier briefly switched gears to share the most recent status of astronomical facilities per James Ulvestad, Chief Officer for Research Facilities. Nothing differed significantly from the update given at the NSF town hall yesterday, though Droegemeier mentioned that the parking lot of the National Solar Observatory’s Boulder facility had been used for COVID-19 drive-through testing till recently. Construction on the dome and telescope mount of the Vera Rubin Observatory are unlikely to resume until September or October.

Droegemeier then pivoted back to OSTP business with an update on the Joint Committee of Research and Enterprise (JCORE), which was formed a little over a year ago. The four areas JCORE focuses on are research security, research integrity and robustness, research administrative workload, and safe and inclusive research environments. Droegemeier emphasized that the committee was continuing to work through the pandemic, especially the research security subcommittee.

In the same vein, Droegemeier spoke about how he had been going around the country to talk to faculty, students, and researchers about research security prior to the pandemic. Lisa Nichols, the OSTP Assistant Director of Academic Engagement, was also part of this effort.

Around this time of year, the OSTP issues an R&D guidance memo to federal agencies, setting priorities for the next fiscal year. The memo is purely guidance and does not contain any funding. Two of the key topics of last year’s memo was American security and “industries of the future” — technologies like artificial intelligence and 5G connectivity.

National High Performance Computing User Facilities Town Hall (by Sanjana Curtis)

The National High Performance Computing (HPC) User Facilities town hall was kicked off by Dr. Richard Gerber (NERSC) who introduced the goals of the town hall: inform the community about HPC and new directions in HPC, discuss opportunities for using HPC to advance astronomy research, communicate what is available at National HPC centers, and gather feedback from the community about their questions, needs and challenges. He also introduced the other presenters from major HPC facilities around the US: Niall Gaffney (TACC, UT Austin), Michael Norman (SDSC, UCSD), Jini Ramprakash (ALCF, Argonne National Lab), Bronson Messer (OLCF, Oak Ridge National Lab), and Bill Kramer (NCSA/Blue Waters, UIUC).

Dr. Gerber defined HPC as computing and analysis for science at a scale beyond what is available locally, for example, at a university. HPC centers have unique resources, including supercomputers, big data systems, wide-area networking for moving data quickly, and ecosystems that are designed for science (for, e.g.: optimized software for simulations, analytics, artificial intelligence and deep learning). These centers also offer lots of support and expertise, since they are staffed by people who are experts in HPC, many of whom have a science background. This helps bridge the gap between the domains of science and computing.

The traditional picture of a supercomputer is a system consisting of hundreds of thousands of the world’s fastest processors, coupled together by very high speed custom networks. Typically, they have a large scratch disk (~petabytes) optimized for reading and writing large chunks of data. These machines were originally designed to have all their compute nodes tightly coupled, where each node needs to know what the other nodes are doing, mainly to solve partial differential equations using linear algebra — they are really good at matrix multiplications! Users interact with supercomputers via SSH and command line, and submit their jobs to a scheduler or queue system for execution.However, the HPC landscape is now changing, and rather abruptly! Single-thread processor performance growth that used to be exponential (Moore’s law-like) has stalled. Instead, we have to rely on parallelism and accelerators for increase in performance. Demand for data analysis is expanding, both from experimental and observational facilities, and large collaborative teams have become the norm. We are also witnessing the rise of artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, and other emerging technologies with new needs.

So what’s next for HPC? According to Dr. Gerber, HPC will continue to advance the limits of computation and analysis. We will see data-intensive science and simulation science merging together, and large scale analysis of experimental and observational data moving to HPC. Since AI and deep learning are here to stay, HPC centers will have to accommodate this demand. Finally, supporting large collaborations will require enabling tools, such as tools for user authentication and data management.

Dr. Niall Gaffney (TACC) was up next, speaking about Astronomy and Advanced Computing in the 21st Century. He started out by mentioning the three pillars of modern computational science: simulation, analytics and machine learning/AI. Astronomy and computing are old friends and there exists a long list of very impressive simulations, such as the Renaissance Simulation, the SciDAC Terascale Supernova Initiative, black hole merger simulations for LIGO, and more! These large simulations are what people typically associate with supercomputing centers. However, there was a shift in this paradigm when SDSS came online and showed astronomy the power of large-scale data and compute resources. The notion of a data center where you could go to run your analysis, without having to download huge quantities of data, was a big change. Now, there is an explosion of AI and machine learning methods, required by facilities like the Vera Rubin Observatory that will generate large amounts of data at very high rates. Astronomy has always been at the forefront of computational science and will continue to drive the field forward.

Not just the three pillars of astronomy, but many observational sciences! Astronomy has been key in pushing this forward. We've always had big data (physics of building a CPU = building a CCD!) #AAS236 pic.twitter.com/EU6t7YG5Ku

— astrobites (@astrobites) June 3, 2020

One benefit of working at an HPC center, according to Dr. Gaffney, is that they are not limited to astronomy. As an example, he cited the use of machine learning to look for anomalies in traffic flows, which is similar to looking for anomalies in data streams coming from telescopes like the LSST! He then discussed the specifications of the Frontera system at TACC, currently the 5th fastest supercomputer in the world and the fastest on any university campus. He concluded by telling us that HPC does not look like it used to! There is a rise of GUI and convenient environments, including Project Jupyter notebooks.

The next speaker was Dr. Michael Norman (SDSC) who talked about their existing system Comet and their plans to deploy a new machine, called Expanse, this summer. Both systems are designed to support the “long tail of science” — small to medium sized HPC batch jobs. Large, full-scale simulations are better done at facilities like TACC. The barrier to entry is low and trial allocations are available within 24 hours! The uniqueness of their new machine, Expanse, comes from its integration with things outside the machine room, such as the cloud and the open science grid. It will support composable systems, containerized computing and cloud bursting. Using the bright cluster manager, the machine will simultaneously have a slurm cluster running the usual batch jobs, and a kubernetes cluster running containerized software!

Soon, will have both Slurm jobs running continuously and Kubernetes jobs running containerized jobs! The divide will be set by user demand #AAS236 pic.twitter.com/IdTt9X0fqN

— astrobites (@astrobites) June 3, 2020

Next, Dr. Gerber highlighted some of the machines at NERSC, including the upcoming Perlmutter, and gave us a breakdown of how their computing time is allotted: 80% DOE Mission Science, 10% Competitive awards run by DOE, 10% Director’s Discretionary Strategic awards.

He was followed by Dr. Jini Ramprakash (ALCF) who described the supercomputing resources available at ALCF: the supercomputer Theta, a smaller system called Iota, the Cooley visualization cluster, and disk and tape storage capabilities. Their big push right now is Aurora, an exascale CPU/GPU machine that should be ready by 2021. Awards exist at different levels, including for getting started (Director’s Discretionary), major awards (INCITE, ALCC), and Targeted Projects (ADSP, ESP).

Dr. Bronson Messer (OLCF) was next. He started out by describing the infrastructure at OLCF — including impressive numbers like their 40 MW power consumption and 6,600 tons of chilled water needed for cooling! Their supercomputer, Summit, is currently the top supercomputer in the world and they have a host of smaller support machines as well. In 2021, they plan to deliver their own exascale machine called Frontier. The big change will be moving from Nvidia GPUs in Summit to AMD GPUs in Frontier. Oak Ridge has been using CPU/GPU hybrid methods for a long time, and will continue to do so. There are three primary user programs for access and allocations are split as 20% Director’s Discretionary, 20% ASCR Leadership Computing Challenge, and 60% INCITE. The allocation application for the Director’s Discretionary program can be found on their website (https://www.olcf.ornl.gov/) and has a one week turnaround!

Wrapping up the town hall was Dr. Bill Kramer (NCSA) discussing Illinois, NCSA and Blue Waters, and the evolution of HPC. The NCSA is the first NSF supercomputing center and Blue Waters is the first NSF Leadership System. It is the largest system Cray has ever built and is also a hybrid containing both CPUs and GPUs. In addition to Blue Waters, the NCSA computational and data resources include Delta (award just announced, details to come), Deep Learning MRI Award (HAL and NANO clusters), iForge (mostly industrial and recharge use) and XSEDE services. Blue Waters has so far provided more than 9.3 billion core-hour equivalents to astronomy, which accounts for over 27% of its total time. Dr. Kramer concluded by reminding us that integrated facilities for modeling, observation/experiment, and machine learning/AI are the future — multipurpose shared facilities are where we are going!

Press Conference: Sweet & Sour on Satellites (by Amber Hornsby)

For the final press conference of the summer AAS meeting, we hear all about satellites — both the good and the bad.

First up, @AstroRach tells us about a hunt for the first stars that were born in the universe. Observations from Hubble suggest they may have formed even earlier than we previously thought — within the first 500 million years after the Big Bang! #AAS236 pic.twitter.com/OgHpP11OPz

— astrobites (@astrobites) June 3, 2020

Kicking off, we first hear from Dr. Rachana Bhatawdekar (ESA/ESTEC) with an exciting update on the hunt for stars in the early universe — they possibly formed much sooner than previously thought. As part of the Hubble Frontier Fields programme, the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) produced some of the deepest observations of galaxy clusters ever. Galaxies located behind the cluster are magnified, thanks to gravitational lensing, which enables the detection of galaxies 10 to 100 times fainter than any previously observed. Through careful subtraction of bright foreground galaxies, Bhatawdekar and collaborators were able to detect galaxies with lower masses than previously seen by Hubble, and at a time when the universe was less than a billion years old. The team believes that these galaxies are the most likely candidates driving the reionization of the universe — the process by which the neutral intergalactic medium was ionised by the first stars and galaxies. Press release

Next up, we hear from Nobel Laureate Prof. John Mather (NASA Goddard Space Flight Center) on hybrid ground/space telescopes and the exciting possibilities of improved observations through artificial stars and antennas in space. Many telescopes use lasers to create an artificial star in the sky, which allows them to track the ever-changing atmosphere, and correct for this effect using adaptive optics. However, Mather and the team are proposing to instead beam a star back down from space to Earth, enabling ground-based telescopes to beat the resolution of space-based telescopes. Another hybrid ground/space telescope suggestion includes dramatically improving the abilities of the Event Horizon Telescope via orbiting antennas.

Moving on from the sweet, Prof. Patrick Seitzer (University of Michigan) introduces the sour theme of the second half of the press conference: large constellations of orbiting satellites and their impact on astronomy. Trails created by satellites saturate an instrument’s detectors and often create so-called ghost images which were briefly mentioned during yesterday’s plenary session on satellite mega constellations. With companies like OneWeb hoping to put more than almost 50,000 satellites in orbit, the future is looking a bit bleak for astronomy, with over 500 satellites contaminating the summer sky every hour, throughout the available observing hours, for the planned Vera Rubin Observatory (VRO). The only positive throughout this is the SpaceX starlink satellites, due to launch this evening, are trialing sun shades to block antennas from reflecting sunlight.

But how do we live with large constellations of satellites? Prof. James Lowenthal (Smith College) discusses the worst case scenario — the impact of satellites on VRO images. With current satellite plans, most of the planned VRO observations will be impossible to schedule, even if we try to avoid satellites. This represents a major collision of technologies between mega constellations and the desire of astronomers to do large-scale survey astronomy. The AAS is seeking out ways to reduce their impact, through surveys of the astronomy community and discussions with both SpaceX and OneWeb. But these two companies are not the only players in the field — so it looks like mega constellations are here to stay, and we will have to work with their operators to target “zero impact” on astronomical observations.

Gone with the Galactic Wind: How Feedback from Massive Stars and Supernovae Shapes Galaxy Evolution (by Haley Wahl)

Our very last plenary of the meeting was given by Dr. Christy Tremonti from the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Tremonti took us on a trip through the process of stellar feedback, showing us what causes it and how it affects star formation.

Feedback is the process by which objects return energy and matter into their surroundings (for example, black holes spewing out jets into the surrounding interstellar medium). In the context of galaxies, feedback is very important because it helps slow down star formation. Without feedback, star formation would progress much more quickly, resulting in galaxies today with very different shapes than what we observe. Feedback influences star formation rates, stellar masses, galactic morphology, and the chemistry of the interstellar medium and circumgalactic medium.

Galactic feedback comes from five major sources. The first of those is supernovae; when massive stars explode, they release an enormous amount of energy into the surrounding interstellar medium, and they create pressurized bubbles of ejected material that expand and sweep up ambient gas. The second is stellar winds, which contribute as much energy and momentum as supernovae, but begin immediately, whereas supernovae effects are delayed by a few million years. The third is radiation pressure on dust grains. When ultraviolet radiation radiation hits a dust grain, it is reradiated in the infrared; these infrared photons carry momentum and in order to conserve it, the dust grains must move, causing the radiation pressure. This can be a significant contributor to the feedback in the center of very dense, dusty galaxies. Another source is photoionization, a process where ionizing ultraviolet photons heat the surrounding gas. The final source of feedback is cosmic rays. Around 10% of a supernova’s energy is thought to be in cosmic rays, and these rays scatter off magnetic homogeneities in the ISM, transferring the cosmic ray momentum to the gas. All of these processes can contribute to the feedback process on different temporal and spatial scales.

The process of feedback creates a cool phenomenon called a “galactic fountain.” Galactic fountains are formed when star formation surface densities are low and isolated superbubbles break out of the disk. When star formation surface densities are high, these superbubbles begin to overlap and they can more efficiently drive centralized outflows. In the local universe, winds are primarily found in starburst galaxies like M82. This galaxy is very close, which allows us to study it in detail.

M82 is a good galaxy to study for galactic winds. Starting with x-rays. Hard x-rays show key feedback processes (blue) #aas236 pic.twitter.com/dqtmtZO0Qs

— astrobites (@astrobites) June 3, 2020

In the future, through multi-wavelength studies and with tools like the Athena X-Ray Observatory (planned for 2030), astronomers hope to make progress relating simulations and observations in order to learn more about the processes of feedback.

It’s a very interesting read!

One minor fact check though: the Tianhe-2, currently ranked 4th fastest supercomputer, is also located in a university campus.