Paper Title: LGBT+ physicists: Harassment, persistence, and uneven

Authors: Ramón S. Barthelemy, Madison Swirtz, Savannah Garmon, Elizabeth H. Simmons, Kyle Reeves, Michael L. Falk, Wouter Deconinck, Elena A. Long, and Timothy J. Atherton

Corresponding Author Affiliation: Department of Physics and Astronomy, The University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA

Status: Published in Physics Review Physics Education Research [open access]

Author’s note: This piece references harassment and other potentially uncomfortable experiences.

All people, regardless of their identities, should feel welcomed and supported in their chosen field. With the growing visibility of LGBTQ+ scientists, students, and faculty in physics comes the need to ensure that each person feels supported and welcomed in their chosen department. Today’s article addresses a study published in Physics Education Research done by professors at the University of Utah, looking at just that issue.

Their findings show significant barriers to entry for LGBTQ+ physicists, especially those who hold intersectional identities and people who are trans. Though this is a familiar issue to many,these results point to significant changes that need to take place to ensure the next generation of physicists feel comfortable and supported.

What do we mean by “department climate”?

Department climate refers to the environment or atmosphere within a particular department, as viewed by its members. This can determine how safe, valued, or respected an individual feels within their learning community. This is especially important when considering responses of a group of people, as is done in this article, since department climate can often make or break a person’s experience within a department. This is often shortened to just “climate”, which is how it will be referred to throughout this article.

Often, addressing climate issues is the responsibility of a committee or group of people doing Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) work. The responsibility of this committee is usually to promote diverse sets of experiences for people entering or working in the department, making sure that all people have equitable access to resources and support, and ensuring people feel fully included in that department.

This comic (above) illustrates the concept of equality and intersectionality, and the additional difficulties people who hold minoritized identities face. This is also a good way to emphasize the difference between equality and equity. While equality gives every individual the same access to resources and opportunities, equity accounts for specific disadvantages and obstacles that certain groups or individuals may experience on the path to obtaining the same outcome. This would mean that in an “equitable” approach, the person on the right would have the materials needed to overcome their unique obstacles.

There is also a list of important definitions, which will be used throughout this Astrobite, described in Section 2 of this paper.

The responses

These authors use a noncomparative framework, called “feminist standpoint theory” to discuss their findings. This means that the authors aim to understand people’s experiences from their own perspectives, rather than compare their experiences to their non-LGBTQ+ peers. This approach allows them to consider intersectional identities that may impact respondents’ experience, rather than focusing only on one part of their experience (which often can’t be considered separately from other aspects of identity; this is key to taking an intersectional approach to understanding experiences).

They implemented a survey, with follow up interviews for some respondents, asking about the experiences of LGBTQ+ people in physics. The demographics of the survey are also important to note, as there were only 6 African American responses (out of 324 total, representing 1.9%), which the authors attribute to underrepresentation in the broader physics community. A majority of the respondents are in academia (grad students, undergrads, faculty, etc), and a majority (82.4%) are white. The authors also point out that there are no responses from trans men, so their experiences are not captured in these results.

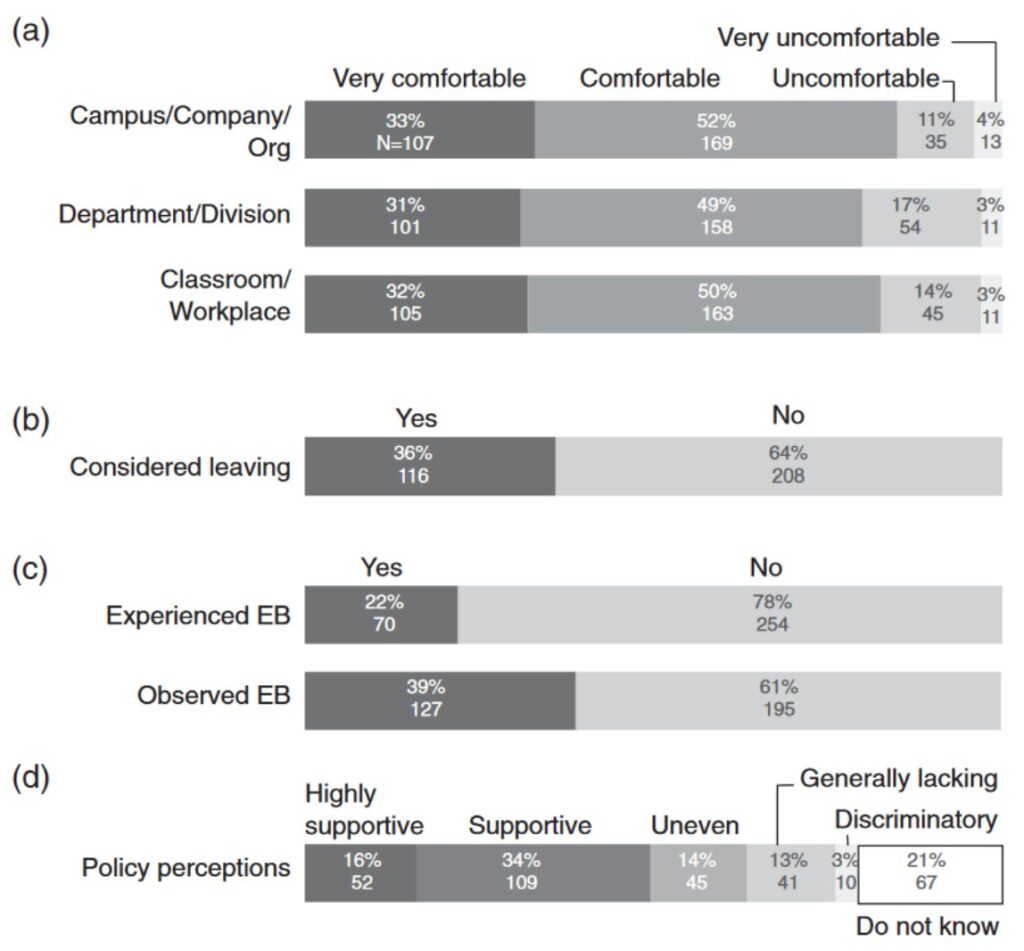

The results of the survey for the entire population of survey respondents can be seen in Figure 1. Of special note is the statistic that 36% of all respondents considered leaving their department in the past year, and the statistics surrounding exclusionary behavior (EB). EB is defined as being shunned, ignored, or harassed due to gender, gender expression, sexual orientation or sexual identity.

The responses: by gender

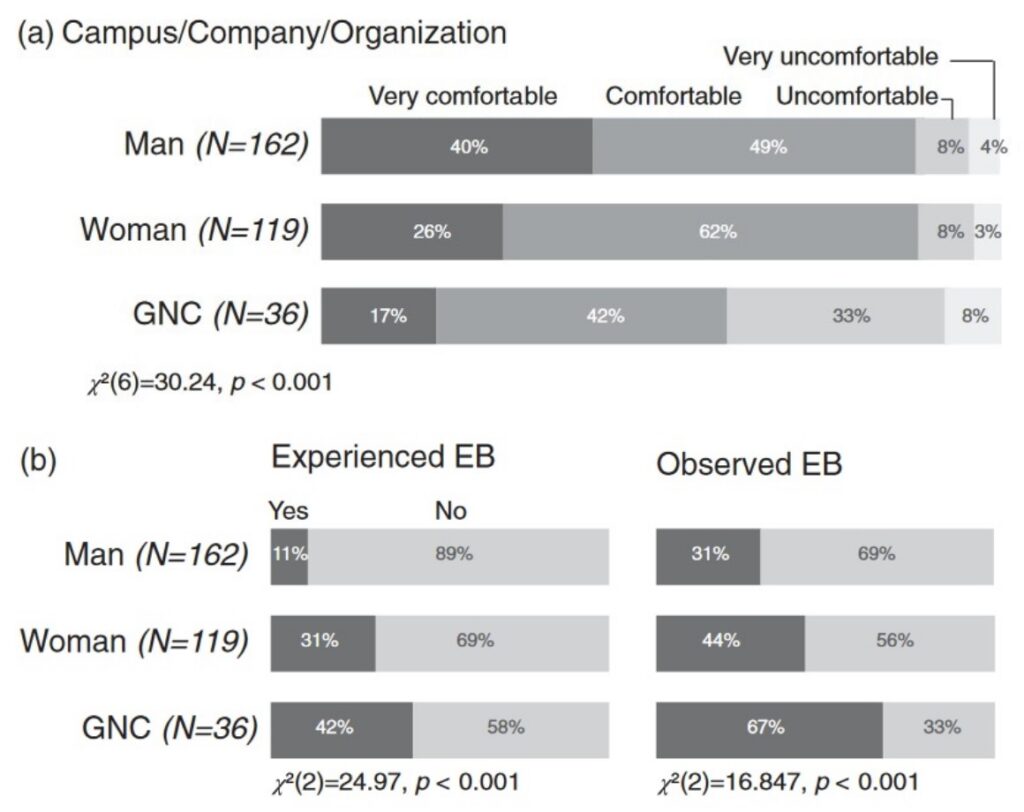

These results did change in some categories by gender of the respondent, as can be seen in Figure 2. Comfort level for their campus/community/organization changed significantly when considering gender of the respondent, with gender non-conforming or non-binary people (GNC) reporting being significantly less comfortable in their community than either men or women.

One of the most striking disparities based on gender is in the category of exclusionary behavior, where GNC people are almost 4 times more likely to report experiencing EB and twice as likely to observe it, compared to 3 times more likely to report experiencing EB for women-identifying people.

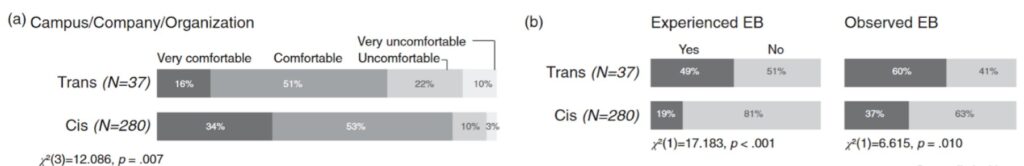

This is even more striking when considering people who identify as transgender (Figure 3). Trans people report being significantly less comfortable in their organization. They also report experiencing EB 2.5 times higher (and observing EB 1.5 times higher) than their cisgender colleagues.

The responses: by race

This study did not find statistically significant differences between non-white and white physicists, which the authors attribute to the limited responses from non-white physicists. What was more striking, however, were the free responses.

As one person said, “I think I grappled more with the race element than I do with the sexuality because the deal is, is that that’s what they see first. I can’t actually closet my race because I’m, [sic] evidently I’m brown, my hair looks different, so it’s just there.”

And another, “it’s been slightly more than a year but my students tend not to believe I’m competent to teach Maths when they see me, because I’m a woman and a minority.”

Intersectional identities for non-white physicists who are also LGBTQ+ are very important when considering how best to support these physicists in their department. Focusing on one element of their experience (LGBTQ+) and ignoring another (race/ethnicity) would overlook an important part of those physicists’ identities, and the complex attitudes they experience in their departments.

Where do we go from here?

There may be many reactions to a paper like this, that points out very heavy issues like harassment and exclusionary behavior.

For some who read these statistics, especially those who do not share one of these identities or have not experienced the same, this may be difficult to process. Understanding people’s experiences is incredibly important to informing how to make systemic changes that benefit everyone in the long run. Drawing attention to issues like this is valuable for a number of reasons, some of which are understanding what support is required, why some people choose to change their career path or transfer programs, and understanding how to move forward.

For some who have experienced the same treatment at a current or former institution or workplace, surveys like this validate their experience and help people to form a community to help them to move forward. It helps us not to feel isolated, and to feel understood by others going through the same things.

In my own opinion, the goal of all departments should be to make their departments as open and welcoming to all people as quickly as possible. Surveys like this give us a starting point in understanding the issue for why so many women, LGBTQ+, and racial and ethnic minorities leave STEM (sometimes referred to as the leaky pipeline). It is the responsibility of departments to take dramatic steps and to choose to change their culture to welcome these students, faculty, and staff members into the field.

Edited by Lindsay DeMarchi

Featured image credit: “Out in Physics” from Symmetry Magazine

Other Astrobites dealing with important and similar themes

Queer Astronomy by Graham Doskoch (parts 1&2)

Quitting a PhD, by Jana Steuer

Why are women leaving astronomy? By Nora Shipp