“The scientist doing basic research may not be at all interested in the practical applications of his work, yet the further progress of industrial development would eventually stagnate if basic scientific research were long neglected.”

“The most important single factor in scientific and technical work is the quality of the personnel employed.”

—Vannevar Bush (“Science, the Endless Frontier”)

The New Year makes me uncomfortable because I’m incapable of keeping Resolutions. So, if you’ll excuse me, I’d like to break from our saturnalia of fresh starts to discuss something rather old. Journey with me in my wayback machine to July 1945, when we’ll witness one of the most important events in American history: the release of the report that motivated federal support of Big Science.

Of course, the summer of ’45 was a happening time. Along with plotting the future of science, people had to deal with World War II. But after the surrender of Nazi Germany and the successful completion of the Manhattan Project, senior American politicians and generals knew that they would soon win the war. And they knew science had led them to victory.

During the war, the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) had virtually unlimited resources and the authority to hand out contracts as it saw fit. Their aggressive investments in new technologies quickly paid off. Penicillin and improved surgical techniques saved the lives of countless soldiers fighting abroad. Radar and a panoply of deadly weaponry—such as the atomic bomb— facilitated the defeat of the enemy.

Before the war, scientific research had primarily relied on private foundations and wealthy benefactors. The OSRD was incredibly effective, but its undemocratic organization and operations were ill-suited to peace. So, the question remained: could the federal government keep accelerating scientific progress?

According to Vannevar Bush, the director of OSRD, the answer was a resounding yes. At the behest of Pres. Roosevelt, he prepared a report, “Science, the Endless Frontier,” in which he argued that America’s relatively prosperous and militarily secure future required a federal program to train and support a large number of scientists and engineers.

Scientists who rely on federal funding—heyo, astronomers!—might want to read this report for two reasons. First, this report was incredibly influential, motivating the creation of the National Science Foundation (NSF) and inserting the idea “basic research” into the public consciousness. Second, this report is a pithy summary of why scientists should pursue basic research and have lots of students. Where better to find inspiration for your next NSF grant’s Broader Impacts than the NSF’s ur-report?

It’s All About People

This report gives little attention to the construction of laboratories and the manufacture of sophisticated instruments and apparatuses. Instead, Dr. Bush focuses on the necessity of training and supporting a large number of researchers.

Vannevar Bush rocking the very important citizen look on one of many occasions when he was doing or saying very important things. (Pielke 2010, Nature)

Cutting-edge science is an elite activity, but, crucially, it can’t be restricted to the economic elite. This report articulates a sentiment that now drives diversity-affirming programs: talent is distributed among people of all backgrounds, so elevating people from only particular backgrounds is a tremendous waste.

Most everyone could benefit from science education. But, you might argue, training a scientist through a graduate degree is tremendously expensive. Might we just identify those with the talent early and focus on them? Unfortunately, you generally can’t predict if a budding scientist will prosper until he or she takes the physics GRE he or she actually starts doing science. Same as it ever was. And scientific methods obviously retain value outside of universities.

The Five Fundamentals

The report laid out five basic rules for supporting scientific research, which federal agencies have (usually) aspired to follow ever since:

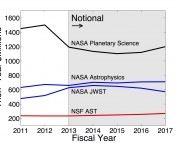

- First, long-term investigations require stable funding. Political power may change hands every few years, but cancer research and space exploration obey no such calendar.

- Second, non-partisan experts should run agencies responsible for allocating funding. The NSF, in particular, awards grants through a “bottom-up” process, where scientists decide which projects in their own specialized sub-field are worth supporting. Someone, however, still needs to set overarching priorities.

- Third, the federal government should fund outside organizations that are not mission-driven, like universities and private research institutes. Corporations fund research with an eye towards near-term profitability; governmental agencies face immediate pressure to produce for policymakers and taxpayers.

- Fourth, the government should supply money, not a bunch of rules. The report is particularly insistent that “the internal control of policy, personnel, and the method and scope of the research” remain under the control of the institution doing the research, providing the flexibility necessary to make basic discoveries.

- Fifth, the President and the Congress must ensure that publicly funded research is in fact conducted for the public’s benefit, though appropriate oversight, budgeting, audits, and the like. This rule is in tension with the others! The struggle to identify the right level of management over enterprise of basic research, which is free-wheeling and failure-rife by necessity, is ongoing.

Dr. Bush intended for a single federal agency to shepherd basic research. Today, research occurs under the aegides of many. However, science is still an endless frontier, and Dr. Bush’s report remains a prescient guide to its exploration.