Earth Week 2024 at Astrobites was all about Indigenous science, and what we can learn by incorporating diverse perspectives in order to improve our stewardship of the Earth in the midst of the climate crisis. For the last (but certainly not least) event in this year’s programming, we heard from co-founder of the Open Cultural Astronomy Forum (OCAF), Dr. Mehrnoosh Tahani. If you’d like to watch the entire talk for yourself, we have a recording archived here as well as a closed caption transcript!

Dr. Mehrnoosh Tahani is a Banting Fellow sponsored by the Canadian government as well as a KIPAC fellow at Stanford University, and lives and works on the lands of the Muwekma Ohlone people. She is an astrophysicist and physicist by training, but collaborates with historians and science historians on a number of projects, including OCAF, a seminar series that Dr. Tahani founded along with Astrobites author Janette Suherli with the support of cultural astronomer and science communicator Ray Norris. It was born from the goal of, as Dr. Tahani says, “embracing and promoting cultural diversity in astronomy”. There have already been a number of seminars, from speakers including Wayne Orchiston, Avivah Yamani, former Astrobites author Mia de los Reyes, Johnson Urama, Duane Hamacher, Jennifer Howse, Robert Fuller, and Hilding Neilson (who also spoke at Thursday’s event)! Anyone can watch the seminars by following the meeting link on OCAF’s website, which lists the dates and times for each talk, links to video recordings of past talks, and shares any useful resources that speakers mention.

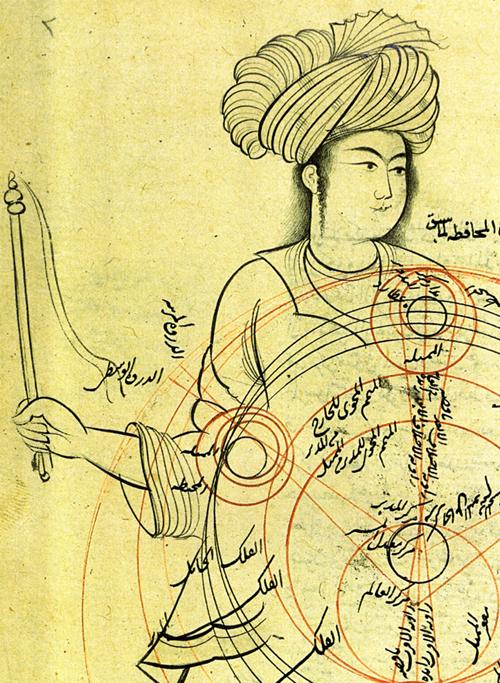

Dr. Tahani was born in Shiraz, Iran, in the province of Fārs, an area which has been significant throughout history for its architecture, scholarship, and archeology. Shiraz’s numerous monuments and historical sites include the Eram Garden, the Pink Mosque or Nasir al-Mulk Mosque, the Tomb of Kings, and the Hafeziyah or Tomb of Hafez, who was a highly influential Iranian poet. Scholars including Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi (author of the medieval manuscript in Figure 1) and Avicenna also made their homes in Shiraz. These scholars, like many in history, were polymaths who used their broad perspectives to draw connections and gain insights that would have been impossible to get from a more specialized expertise, including innovations in astronomy and mathematics.

Also near Shiraz is the Persepolis, or Takht-e Jamshīd, built in around 515 B. C. E. during the time of the Achaemenid Empire, of which modern-day Fārs was the capital under the empire’s founder, Cyrus the Great. Although it was burned down in 330 B. C. E. by Alexander III of Macedon1, the remains of Persepolis, depicted in Figure 2, are now a World Heritage Site. When she visited in 2017, Dr. Tahani says she “was struck by the level of knowledge, architecture, and design in building this monument”. The Achaemenid Empire is notable in history for its high level of cultural tolerance and respect3, even as it covered a truly vast amount of territory, stretching at its height as far west as Libya and Macedonia and as far east as Pakistan, and Dr. Tahani takes great pride in this millennia-old legacy of diversity, inclusion, and cultural preservation in the place where she was born4.

Dr. Tahani moved to Canada for her graduate studies, living first in Regina, SK, then moving to Calgary, AB, and finally Penticton, BC. Through friendships with Indigenous people in Saskatchewan, as well as her experiences in a non-inclusive academic system, she began to think about how astronomy as a field can be made more friendly to people from marginalized and minoritized cultures, including Indigenous ones. Many of the cultural values that she saw in her Indigenous friends reminded her of her family and friends in Iran, and she was struck by the kindness and welcome that she received. These values are not reflected in the culture of the Western academic system, but Dr. Tahani is working to change that.

Again and again throughout her talk, Dr. Tahani returned to how inspired she feels by the field of cultural astronomy, and by learning about both the history of her own homeland’s astronomy and the astronomy of other cultures. Sometimes we even have more in common than we might think! She pointed to a 2021 paper by Ray and Barnaby Norris that suggests many of the stories associated with the Pleiades star cluster by cultures across the world may descend from one single story5 dating back to before 100,000 BCE! Dr. Tahani is currently working with Kaveh Niazi and Kioumars Ghereghlou at Stanford University to produce an exhibition on historical and cultural astronomy with a specific emphasis on Persian, Iranian, and Islamic stories like the Pleiades, which are called the Seven Marks or Seven Thrones in Persian.

Dr. Tahani closed her talk with the invocation, “Let the sky connect us and bring us together, and let’s embrace our differences and cherish our similarities.” Astronomy is one of the oldest sciences, and it’s been practiced in a variety of different ways by cultures around the world since time immemorial. Cultural diversity is baked into the history of our field, and it’s important that we learn about and acknowledge the myriad of diverse perspectives in both our history and our current reality.

Astrobite edited by: Olivia Cooper

Featured image credit: Suchitra Narayanan

- aka Alexander the Maybe Not That Great, Actually

- In epicyclic models, planets were assumed to travel in small circles called epicycles within their larger orbits around the Earth, similarly to how we now understand the Moon to orbit the Earth while the entire system simultaneously orbits the Sun. This model produced highly accurate predictions of planetary motion, and was the state of the art until it was discovered that elliptical orbits in a heliocentric system predicted the observations equally well.

- Cyrus the Great is well-documented in his religious tolerance in particular, providing funding for temple construction and restoration, respecting holy sites belonging to other religions, and generally allowing any religion to be practiced freely in his empire. He is credited in the Books of Ezra and 2 Chronicles for allowing the Jewish people to return to the Holy Land after their exile in Babylon, and with funding the construction of a new temple in Jerusalem out of the royal treasury.

- Even after the religious tolerance of ancient Persia had collapsed, people in Iran continued to uphold and preserve their culture. Dr. Tahani specifically pointed to the epic poem Shahnameh, or Book of Kings, written between 977 and 1010 C. E. by the poet Ferdowsi. The Shahnameh was written in Persian at a time where the Persian people were not officially allowed to speak their own language, and is widely regarded as a literary masterpiece. Despite its status as the longest poem ever composed by a single author, it’s widely read even today, and Dr. Tahani grew up reading it!

- The Pleiades story is fascinating and I highly recommend you check out the paper by Norris & Norris, but the idea is that cultures around the world tell stories about seven entities (usually sisters or princesses), where one of their number is forced to leave, sometimes for reasons involving the constellation the Greeks knew as Orion. This corresponds to the fact that although there are seven stars bright enough to be seen by the naked eye in the Pleiades cluster, two of them are too close together to be distinguishable. The fact that these stories are so similar even when they occur in cultures that had no pre-colonial contact, as well as the plot of the story involving seven sisters of whom one is missing, indicates that this story might date back in some form or another to the last time those two stars were far enough from each other to distinguish them with the naked eye–100,000 years ago, before any humans had migrated out of Africa.

This article was written as part of our Climate Change Series. We’d love to hear what you would like to see from this initiative – if you have ideas, please let us know in this google form. Find last year’s Earth Week page here.