It’s a familiar experience: sitting down to your desk with a big pile of data in front of you. You’re looking at the results of a difficult and expensive observing run, one that required months of preparation to pull off. Before you went, you spent days thinking about what data you needed and how best to get it, not to mention weeks petitioning your superiors for access to costly equipment and facilities. And even once you started gathering information, it was still a matter of luck as to how much you’d get and of what quality it would be. Now that it’s all here, you have to sit down for the next step: analyzing and processing it, teasing out high-level conclusions from the raw data while accounting for all possible errors and referring back to your peers’ work on the subject. When you’ve finally managed that, you’ll write it all down and send it off for review, and with any luck you’ll have shed some light on the current state of nuclear weapons programs in Iran.

Wait, what?

Astronomy has a kindred cousin, a cool one who wears his sunglasses at night: intelligence analysis. I don’t just mean reconnaissance satellites, either; the process of astronomy, that of observing and drawing conclusions, is possibly the most similar of all the sciences to the process of intelligence gathering. Both fields deal with low signal-to-noise regimes that are based primarily on observation rather than experimentation. Both fields must ask and answer the question, “What instruments/equipment/facilities do I need to gather the data necessary to draw a conclusion?” Both fields must continually account for errors and biases that could easily lead to false or falsely credited conclusions.

There are some key differences. For instance, astronomy is not usually time-critical, and (to my knowledge) no one’s ever managed to topple a government with it, though we have upset quite a few celestial orders. None of the studied objects in astronomy are deliberately attempting to deceive you, although in many cases it is incredibly easy to deceive yourself about what you are seeing. Intelligence also gets a bigger budget (not that I’m bitter or anything). Intelligence reports are not often peer-reviewed, matters of state rarely follow equations of state, and the subject material changes so fast that long-term, rigorous descriptions are not practical. But other than these immediate concerns, the two are remarkably similar fields of study. And thus it behooves us as astronomers to learn from our cousins on the other side of the fence, who may not have been in the business quite as long or have quite as much ground to cover, but who certainly have a lot more pressure to produce results. That’s why today I’m going to be talking about Robert M. Clark’s key textbook Intelligence Analysis: A Target-Centric Approach, and what lessons it holds for you as a professional scientist.

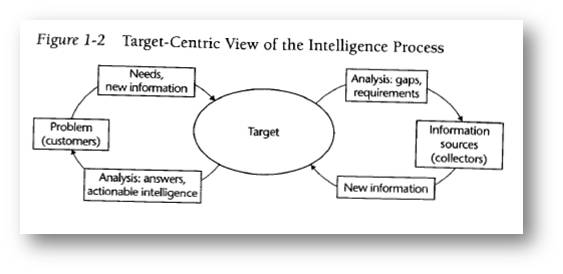

First, a little background. Intelligence Analysis: A Target-Centric Approach was published in 2003 by Robert Clark, a career intelligence analyst and faculty member of the CIA’s Intelligence Community Officers’ Course. While teaching this course, he developed (along with some key colleagues) the method of target-centric analysis, the subject of the book and a new alternative to the traditional intelligence cycle. In brief, while the traditional cycle goes Question Posed —> Intelligence Gathered —> Intelligence Analyzed —> Report Returned, the target-centric method proposes an ongoing cycle of gathering and analysis devoted to the creation of a single target model, which intelligence consumers may then query for answers.

First, a little background. Intelligence Analysis: A Target-Centric Approach was published in 2003 by Robert Clark, a career intelligence analyst and faculty member of the CIA’s Intelligence Community Officers’ Course. While teaching this course, he developed (along with some key colleagues) the method of target-centric analysis, the subject of the book and a new alternative to the traditional intelligence cycle. In brief, while the traditional cycle goes Question Posed —> Intelligence Gathered —> Intelligence Analyzed —> Report Returned, the target-centric method proposes an ongoing cycle of gathering and analysis devoted to the creation of a single target model, which intelligence consumers may then query for answers.

This method should seem immediately familiar to any scientist, because it’s the exact technique we’ve all been using for decades. We tend to think about scientific research via The Scientific Method (™) that you learned in high school: formulate hypothesis, design study, gather data, analyze data, accept or reject hypothesis. This is a great way to think about a single scientific experiment, but it’s a terrible way to think about a research career and about science as a whole. The Scientific Method as learned in high school is similar to the traditional intelligence cycle: ask question, gather data, answer question. It doesn’t include the concept of a larger, living model that grows and evolves and can be built upon to answer future questions. When you want to know how a pair of quarks interact, you don’t make up a hypothesis out of thin air; you ask QCD. How did that mountain get there? Don’t spend your life analyzing it; ask the theory of plate tectonics. The Scientific Method is good enough for the science fair, but real, persistent scientific research advances are made through a target-centric approach.

All the great theories and models in science are triumphs of target-centric analysis: the Standard Model, the Big Bang, plate tectonics, DNA and the cellular model of life, valence electrons and chemical bonds, evolution, and relativity, just to name a few. These grand models enclose whole submodels, which themselves enclose further models, and so on and so forth. In the end, all of science is one great target-centric analysis question, the subject and goal of which is nothing less than modeling The Universe. And scientists are continually acting as both consumers and analysts of these models: both asking questions and receiving answers to allow them to pursue further work, as well as gathering data to fill in gaps and test the assumptions and conclusions of these models. When writing a research proposal, it’s not enough to simply say, “I plan to observe Mg II in the extended gas halos of galaxies.” You need to put this in the context of both a question asked of a model and data that will feed back into it; for example, “Galactic evolution models predict that star formation quenching will move enriched gas out into these halos. I will look for this gas. If I don’t find it, that will be an important fact that tells us that part of the model is wrong as it currently stands. If I do find it, but find that it prefers a certain type of galaxy – red or blue, for instance – then this is additional information that will help to expand and detail the galactic evolution model.” You have framed your research both in terms of the model it is drawing from and the model it will be incorporated into, and in the process demonstrated why it is worth doing: this research is important to the star formation quenching model, which is in turn important to the galactic evolution model, which is in its turn vital to our model of cosmology and the evolution of the universe as a whole.

Once you begin to consider your research in this way, it becomes much easier to think about what you’re doing and understand where you should go with it. When undertaking a research project, frame it in terms of models – what models am I going to use, and what models will eventually incorporate my results? Some scientists lean more towards being consumers of models, and some lean more towards building them; it may be that you have a predilection for one over the other. There are distinct partnerships in astronomy between the two; for example, the partnership between the computational modelers of Type Ia supernovae and the cosmologists who use them as distance measurements. The cosmologists are consumers of the Type Ia models built by the supernova astronomers; the cosmologists are in turn builders of the cosmological expansion models, and the supernova astronomers are in turn consumers of models of fluid dynamics, neutrino physics, general relativity, and so forth. Think about what models you interact with on a daily basis, and which ones you would like to build vs. consume. You might gain some insights on what directions in research you will find the most fulfilling.

Intelligence Analysis: A Target-Centric Approach is not all applicable to scientific research. Several chapters of the book go into great detail about the different types of intelligence gathering and their advantages and drawbacks, which aren’t exactly relevant (unless you’re interested in cute tricks to do with infrared observations). But it’s a good read, and fast, and it will teach you how to think about questions and models in a new and more productive light. It’s entirely possible that you’re already using the techniques described in this book, but you’ve never seen them laid out. The book itself is a bare 285 pages and is written in a simple, engaging style, as befits a textbook for people who aren’t used to dry engineering tomes. As an extra exciting bonus, it also discusses problems of reconciling differing pieces of information, how not to get into a groupthink mentality, the hallmarks of dubious or biased information, and how to correctly and consistently present your conclusions to your customer – all of which are important things to learn in a professional research career. All in all, this book will teach how to better organize your thinking and your research. And who knows, maybe once you get your PhD you’ll decide to don your cloak and receive your dagger instead.

You can pick up Intelligence Analysis: A Target-Centric Approach here on Amazon for about $45, depending on whether you buy new or used. You may also be able to find a free PDF if you google around, but I wouldn’t dream of encouraging such behavior.

Dear Elizabeth,

Some friends of mine in the US intelligence community forwarded me your post on “Target-Centric Astronomy.” I am delighted by your extension of my book’s basic themes into one of the purest of scientific disciplines. It is an insightful and perceptive comparison.

However, I do think you may have missed your calling, as much as you seem to enjoy your present one. Looking at the assessments in your post, you’d make a first-rank intelligence analyst. You obviously take the multidisciplinary perspective that is essential in producing good predictive intelligence. You’d have been disappointed, though, to find that we analysts don’t wear sunglasses at night. Of course, we are cool in different ways . . .

Thanks again,

Bob Clark