Today’s Astrobite is a guest post by Kevin Schawinski, an Einstein Fellow at the Yale Center for Astronomy & Astrophysics and a co-founder of GalaxyZoo.

Computers are great for dealing with some problems, but they can utterly fail at others. Usually the latter kind of problems get handed to grad students to sort through by hand. They often involve some kind of pattern recognition task, which is something the human brain excels at. Many planetary scientists are intimately familiar with a small fraction of the surface of some solar system body and I have looked at more images of SDSS galaxies than anyone should – I classified nearly 50,000 galaxies in a week.

But what about the remaining 950,000? How could I possibly classify all of them? The science case was compelling, but the task was beyond me. So one evening in the Royal Oak, a pub in Oxford, Chris Lintott (@chrislintott) and I came up with the idea of asking people over the internet for help: we would try and crowdsource visual galaxy morphology classification!

We assembled a team and quickly built a website – galaxyzoo.org – and database to record clicks from volunteers whom we hoped to recruit from across the world. Some of the key design choices that went into the site turned out to be critical: simple design, an intuitive interface and a brief tutorial. People on the web don’t read long manuals.

The original Galaxy Zoo interface. The user is shown an image of a galaxy and via a set of simple, intuitive buttons, can classify the current object. After clicking, another randomly selected galaxy is shown.

The site launched and we put out a press release and within hours we were logging more classifications per hour than I could generate in a whole week. This had the unfortunate side effect of crashing the SDSS server at Fermilab as we did not anticipate the great interest the site was generating as the story spread through the web ecology of new sites, aggregators and social media. A quick, heroic emergency fix was put in place by our colleagues at Johns Hopkins and the site was back up.

Within a year, a quarter of a million people had logged more than 70 classification for each of the ~1 million SDSS galaxies. So not only did we have human, visual classifications for each galaxy, we could also tap into the wisdom of crowds and assess just how certain each classification is. The data from Galaxy Zoo 1 are now all public at data.galaxyzoo.org and are shared as tables on the SDSS Casjobs site.

Having so many people pour over the data and having them link up and build a community around a forum (galaxyzooforum.org) and associated social media (twitter, facebook) and even real-life meet-ups in places as varied as New York, Greenwich and Northern Ireland also had another benefit: humans are great at spotting things that are unusual.

Discoveries made this way by citizen scientists include:

Hubble Space Telescope image of Hanny’s Voorwerp, the light echo of a recently deceased quasar in the galaxy next to it. A mere ~200,000 years ago, IC 2497 with a redshift of z=0.05 was the nearest powerful quasar to us by far.

• Hanny’s Voorwerp, the death scream of the nearest quasar to us (named after citizen scientist Hanny van Arkel @hannyvanarkel).

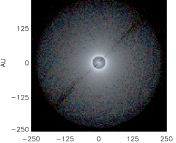

• The green peas, a new class of extreme, compact starburst galaxies with very low metallicities. They were spotted by the `peas corps’ to `give peas a chance.’

• The Voorwerpjes (or little Voorwerps), clouds of ionized gas around local galaxies similar to Hanny’s Voorwerp but powered by lower-luminosity AGN.

The success of the Galaxy Zoo inspired us and others joining us to launch a number of new projects. Galaxy Zoo taught us valuable lessons about how to run a citizen science project and our developers, led by the indefatigable Arfon Smith (@arfon), have build the front- and backend software tools needed to get new citizen science projects up and running in no time. Thus, the Zooniverse (zooniverse.org, @the_zooniverse) was born!

Astronomy projects so far include:

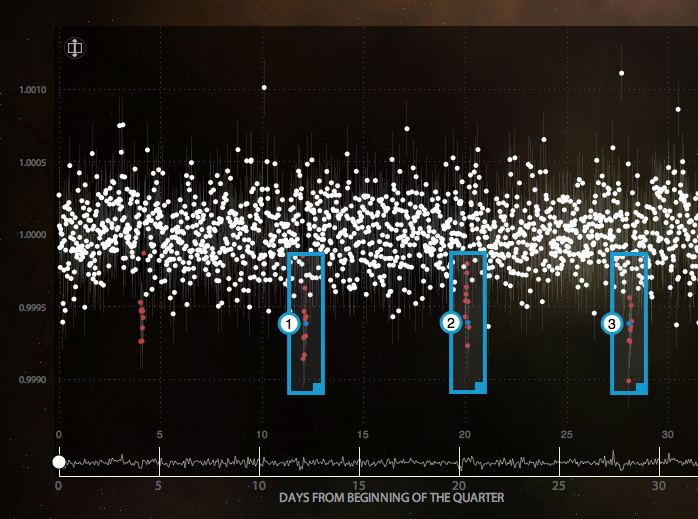

• planethunters.org – crowdsourced Kepler light curves, with the first planet candidates spotted by citizen scientist already published.

• milkywayproject.org – Recognizing bubbles and complex structures in the Milky Way from archival Spitzer imaing.

• solarstormwatch.com – Spot solar flares and storms in real time as the STEREO mission monitors our sun.

The Zooniverse is now also hosting project outside of astronomy as the citizen science approach is useful in many areas of science and research:

• oldweather.org – citizen scientists help digitize ships logs for weather data at sea that is vital input in climate models and simulations.

• whale.fm – people can listen to recordings of whale conversations to help understand them better.

Now, you’re thinking, how can I get started with my own citizen science project? My supervisor dumped this mountain of data on my desk and jetted off to a conference at a beach resort and it’s going to take me years to get through the “first look”. Fret not, the Zooniverse may be able to help! If you have a compelling case for a new project, head over to http://www.

Hi!

As a person who first realised, together with John Raddick, that Galaxy Zoo should be an international project, and helped to put this idea into practice, I am annoyed by the way you consistently neglect to mention effort put in the Zooniverse by people who have taken care that this project has really international, earth-wide dimension and is not confined into English-speaking community.

Great summary of the history of the Zooniverse Kevin! 🙂

Hi Lech,

we definitely don’t forget all the users across the world who are helping make our citizen science projects a success! In fact, many of us are busy translating the projects into more and more languages to make sure that people from all over the globe can contribute and be part of our community!

Cheers,

Kevin