Title: A Vast Thin Plane of Co-rotating Dwarf Galaxies Orbiting the Andromeda Galaxy

Authors: Rodrigo A. Ibata, Geraint F. Lewis, Anthony R. Conn, et al.

First Author’s Institution: Observatoire astronomique de Strasbourg, 11, rue de l’Université, F-67000 Strasbourg, France

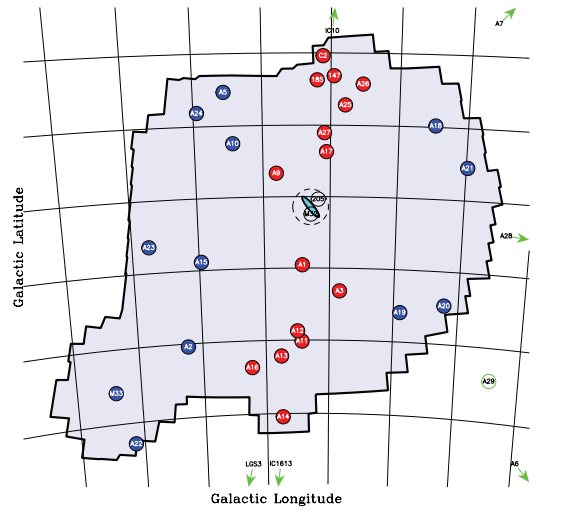

Fig. 1: The distribution of dwarf galaxies around Andromeda. The filled circles represent the dwarf galaxies used in this analysis. The PAndAS survey area is shaded in blue. The red circles are those galaxies that lie in a plane centered on Andromeda. (Figure 1 of Ibata et al)

As the only giant galaxy in our local neighborhood, Andromeda (M31) provides a unique laboratory to study the structure and properties of massive spiral galaxies. The formation history of large spiral galaxies, like Andromeda and the Milky Way, is a question of particular interest to astronomers today. One method of probing this evolutionary past is to study the numerous faint dwarf galaxies that orbit the larger central galaxy. These small galaxies are thought to be the remnants of the complicated process that produces the massive central galaxy. Careful study of the dwarf galaxies surrounding Andromeda can provide key insights into the galaxy formation process.

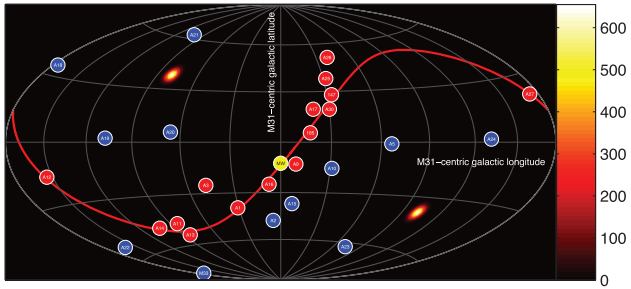

Using the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope, the authors have constructed a large-scale panoramic image of Andromeda and its several dwarf satellites, as part of the Pan-Andromeda Archaeological Survey (PAndAS). The two-dimensional distribution of these satellite galaxies on the sky is shown in Figure 1. Distance measurements for 27 of the dwarf galaxies were obtained using the brightnesses of red giant stars in the individual satellites. Using these precise distances, the authors are able to make a three-dimensional image of the satellite positions as they would appear if viewed from Andromeda. The projection of this 3D image is shown in the figure below, where the disk of Andromeda lies along the equator of the projection.

Fig. 2: The satellite galaxy positions as viewed from Andromeda. The disk of Andromeda lies along the equator of the projection. The red circles are those galaxies that lie in a plane centered on Andromeda. (Figure 2 of Ibata et al)

Upon visual inspection of the three-dimensional image, the authors noticed something unexpected about the spatial distribution of the dwarf galaxies. Rather than a random distribution of satellites, they found that 15 of the satellite galaxies (marked in red in the above figures) are aligned in a planar structure, which is nearly a million light years in diameter but only 30,000 light years thick. The probability of such an alignment occurring by random chance is a minuscule 0.13%. The authors also measured the velocities of these satellite galaxies and found that 13 of the 15 galaxies are coherently rotating around Andromeda. They conclude that these results indicate the presence of a planar structure of satellite galaxies around Andromeda with a confidence level of 99.998%.

It is important to note that a planar distribution of satellite galaxies has also been observed around the Milky Way, the only other galaxy where such a mapping is possible. Can current theories of galaxy formation in a ΛCDM universe account for the planar structure around large spiral galaxies? This remains an open question in the astronomy community. Some simulations of the formation of Andromeda-like galaxies seem to be able to produce flattened structures of satellite galaxies, although such structures would be quite rare. Other studies have argued that the existence of a such a structure is inconsistent with our cosmological framework. There still remains much uncertainty surrounding the formation of Andromeda-like galaxies, but the authors’ discovery will surely ignite a flurry of both observational and theoretical work.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks