“It’s tricky to rock a rhyme

to rock a rhyme that’s right on time

It’s tricky… it’s tricky (tricky) tricky (tricky)”

–Run-D.M.C., “It’s Tricky”

Long-term planning is hard, especially in a democracy. America’s elected regimes have short residence times, as Presidents come and go and control of Congress swings back and forth between parties. But ambitious astronomy—the kind that rewrites textbooks—may take decades to plan and execute. Building a large telescope or sending a spacecraft to another planet, for example, requires policymakers to embrace a common goal and to stay the course for many years, shielding scientific workers from the shifting whims of politicians.

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) is the largest individual sponsor of astrophysics and planetary science in the world, as discussed in our last romp through the landscape of science policy. Does NASA have a strategic direction that guides its priorities and activities?

Not a coherent one, according to a new report from the National Research Council (NRC). An NRC committee, composed of experts from academia, government, and private industry, spent a year visiting every NASA field center, hearing testimony from policymakers and bureaucrats, and surveying the public. They concluded, “there is no national consensus on strategic goals and objectives for NASA. Absent such a consensus, NASA cannot reasonably be expected to develop enduring strategic priorities.” Certainly, the uncertain future of human spaceflight causes most of this angst. But scientists struggle, too, against strategic realities that temper our dreams. The overall turmoil at NASA threatens the ability of scientific communities to prepare strategic plans.

The National Research Council, part of the National Academies, is a private, nonprofit, nonpartisan institution that provides expert advice on scientific and technical matters.

How does science fit within NASA’s strategic direction?

Most people are confused about whether NASA has a strategic direction. Neither NASA’s vision nor mission statements include the words “aeronautics” or “space”. When the Space Shuttle program ended, a substantial fraction of the general public (along with many news reporters) surmised that NASA was closing up shop. As long as the human spaceflight program lacks a clear goal, policymakers and the public will say that NASA is adrift, even if astrophysicists and planetary scientists continue launching a panoply of missions. Moreover, scientists suffer programmatic whiplash whenever the human spaceflight program is redirected; investigations of the Moon, say, may be abandoned in favor of robotic precursor missions to Mars.

People agree that NASA should have a clear direction, but a consensus vision is currently lacking. If you ask ten different people what NASA should be doing, you’ll likely get ten different answers. Even during the halcyon days of the Apollo program, many people opposed spending a great deal of money on space exploration. Some people think humans ought to colonize the galaxy; others want to remain safe and snug on Earth, only sending robots out to explore. Maybe science and discovery is its own reward—or does NASA need to justify its funding with technological spinoffs and other economic boons?

Right now, NASA is attempting to do a little bit of everything. As a result, nearly all aspects of NASA’s portfolio are shortchanged. The NRC committee bluntly stated the essential problem, “the approach to and pace of a number of NASA’s programs projects, and activities will not be sustainable if the NASA budget remains flat, as currently projected.” Something has got to give—to have a strategic direction, NASA must trim its ambition.

The NRC committee highlighted four paths to allowing NASA to develop an appropriate strategic direction. First, Congress could increase the size of the NASA budget—optimal, but unlikely. Second, the NASA field centers could be aggressively restructured to improve efficiency, which would probably involve firing personnel and shuttering underused facilities. Third, NASA could vastly increase the scope of cost-sharing partnerships with other nations, governmental agencies, or private sector entities. Finally, NASA could limit the breadth of its activities, abandoning human spaceflight, say, to make grand strides in Earth and space science, or vice versa.

Endeavour lands at Los Angeles International Airport, the last flight of a space shuttle orbiter. What does NASA do now?

While there is no consensus on strategic goals and objectives for NASA as a whole, however, there are well-defined plans for advancing astrophysics and planetary science. Our challenge, as scientists, is to find the resources necessary to fulfill our vision in a hostile political climate.

What are the strategic plans for science? What’s holding them back?

Every ten years, the NRC conducts surveys (called “decadal surveys” or simply “decadals”) of various scientific communities, like astrophysics and planetary science. These expansive efforts deserve Astrobites of their own! Briefly, a decadal survey contains a prioritized portfolio of space missions, terrestrial research, and technology development that is designed to answer a set of compelling science questions. Congress usually mandates, through authorizing and appropriations legislation, that federal agencies like NASA heed the recommendations of these decadals, which represent a near-consensus of scientists.

Previous decadals are responsible for everything from the continued operation of the Hubble Space Telescope to the Curiosity rover currently exploring Gale Crater on Mars. The latest surveys offered exciting programs of scientific exploration. New Worlds, New Horizons in Astronomy and Astrophysics (2010-2020) promotes the Wide-Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST) and the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST), which would expand the frontiers of dark energy and exoplanet research, along with much else. Likewise, Vision and Voyages for Planetary Science (2013-2022) describes a diverse set of missions to destinations throughout the solar system, including the beginning of a campaign to retrieve carefully selected samples from the surface of Mars. Unfortunately, few of these missions will be executed as originally envisioned.

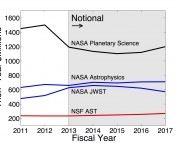

As noted by the NRC committee, “even the best strategic plan is vulnerable to severe changes in the assumptions that underlie its development.” The decadals assumed that budgets would increase, at least to match inflation, year after year. A growing hostility to federal spending in Washington, D.C., however, rudely recalibrated expectations—flat is the new up. Realistic budgets will not accomodate many new missions, especially because many missions currently operating or under development, like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), are experiencing massive cost overruns. The astrophysics decadal, in particular, is essentially shelved for the next several years, until JWST launches.

Exploration of our universe won’t continue on its own. It’s tricky. Astrophysics and planetary science must compete with myriad other priorities for limited funding and expertise. Like it or not, the battle to restore support to space science is part of the larger war over the purpose of NASA and related agencies. How can scientists preserve their strategic planning process amid general turmoil at NASA? Do scientists need to justify their efforts apart from human spaceflight? Or might we join forces with the human spaceflight community to achieve shared goals? How do you think we could improve our strategic thinking?