Caption: H. A. Sawyer loading plates into the Harvard 16” Metcalf Doublet telescope. Picture from http://hea-www.harvard.edu/DASCH/telescopes.php

- Paper Title: 100-year DASCH Light Curves of Kepler Planet-Candidate Host Stars

- Authors: S. Tang et al

- First Author’s Affiliation: Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Cambridge, MA; Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics, Santa Barbara, CA; California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA

- Journal: Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific (Submitted)

Introduction: the DASCH project

Astronomy has advanced in leaps and bounds over the last few hundred years. Perhaps the single greatest advance has been the switch from observing with our eyes to observing with cameras. Where once we inspected the heavens with our eyes and relied on sketches to record what we saw, now we attach imaging mechanisms directly to the telescope. Not only does this allow us to collect more photons, imaging mechanisms also give us the ability to store data for later analysis. A little more than a century ago, astronomers at Harvard made the switch to using photographic plates to image the heavens. Each plate, once analyzed, was cataloged, archived, and forgotten…until now.

Researchers at Harvard recently recognized the promise of the data being held in these archives. Over a century’s worth of observations of the sky are recorded in these plates. By contrast, most objects observed as part of other projects have no more than a few decades worth of observations at best. This dataset offers us the remarkable opportunity to study how stars have evolved over almost a century. Who knows what long-term trends or cycles might be identified?

To realize the potential of this dataset and answer questions like these, the DASCH project (Digital Access to a Sky Century) project was created. This project aims to scan and digitize the entirety of Harvard’s plate archive, converting into usable form for today’s astronomers and their analytical techniques.

Role of This Work: Variability in the Kepler Field

A number of exciting discoveries have already been made with this data, including the discovery of a 5-year dust accretion event on the eclipsing binary KU Cyg and the observation of century-scale variability in K-giants. The paper explored in today’s Astrobite explores what the DASCH dataset can tell us about exoplanets. In particular, it looks at Kepler planet candidate host stars, and asks if we can distinguish variability in them. The variability of the host stars is important to understanding the planet environment. Long-term variability in stellar output would influence the composition and size of a planet’s atmosphere. Similarly, if a star is prone to occasional catastrophic flares, this would impact the atmospheres of orbiting planets – and their prospects for life. Interactions between close-orbiting giant planets and their parent stars might influence such flare events. The DASCH data can place constraints on long-term variability and flare rates.

Data and Results

The authors constructed time series lightcurves for the 997 stars with planet candidates from the 2011 release of the Kepler data. Of these, 261 stars had at least 10 good observations over the course of the DASCH data, and 109 of them had at least 100. Brighter stars had more observations, as they showed up in more plates.

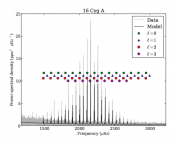

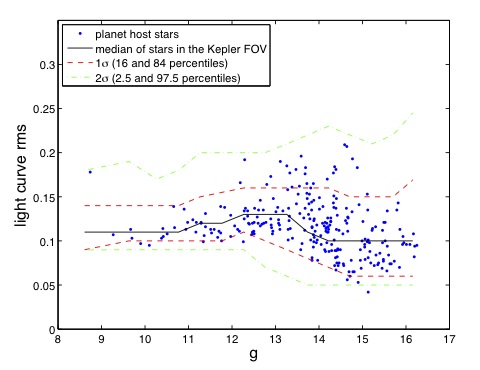

Figure 1 presents sample lightcurves for the Kepler stars. Figure 2 presents the variability of the 240 Kepler host stars with more than 10 DASCH points and no contaminating stars as a function of magnitude (brightness). Note the decrease in scatter with higher magnitude (lower brightness); this is because the fainter stars were only observed in the high-quality deep field plates, improving the precision of observation.

Figure 1: Sample lightcurves for 4 stars thought to host planets from DASCH. The green dots are the modern-day Kepler lightcurves for these objects. The DASCH data is much less precise, but covers a far larger temporal range.

Figure 2: Variability for the Kepler planet hosts (y-axis) as a function of magnitude (brightness, x-axis). The black line is the median variability for the stars in the Kepler field. The red and green lines are the 1 and 2 sigma contours for the variability of the stars in the Kepler field. None of the planet hosts are particularly variable.

None of the stars studied show flares or long-term trends at the 3-sigma level. This is a remarkable statement: the Kepler planet hosts are shown to be stable to within 0.4 magnitudes over a timescale of 100 years! This result rules out large-scale flares or variance in insolation on this scale. This is promising from a habitability perspective, as life prefers stable environments.

We look forward to further innovative discoveries from DASCH!