Title: Evolution And Persistence of Students’ Astronomy Career Interests: A Gender Study

Authors: Zoey Bergstrom, Philip Sadler & Gerhard Sonnert

First Author’s Institution: Harvard University

Status: Published in the Journal of Astronomy & Earth Sciences Education

A book, a teacher or even a ride with Ms. Frizzle: each of our readers has something that ignited their passion for astronomy. Often, these catalysts are designed to throw us into the depths of curiosity at an early age, with the hopes that we’ll get hooked. Today’s Bite focuses on formally tying together children’s pastimes, their interest levels in Astronomy and what we can do to inspire others.

The study examines students’ interests in Astronomy through middle school and high school. (For our non-American audience, these are roughly between the ages of 11 and 18.) These stages for the beginning of what is known as the “leaky pipe,” in which people who are initially excited about a career in STEM eventually leave the field. The question is: Where does this pipe “begin” and how can we patch up early leaks?

To address these questions, the authors used the National Science Foundation’s OPSCI survey, which surveyed just under 16,000 students in introductory English courses from universities around the United States. The researchers asked students what they wanted to become at four points in their life: during middle school, at the beginning of high school, at the end of high school and at the beginning of college. For example, a student could check off that they were interested in becoming an “Astronomer” during middle school but not interested afterwards. Additionally, students were asked about any interests they had growing up, including “[taking] care of a trained animal” or “[watching] science fiction.”

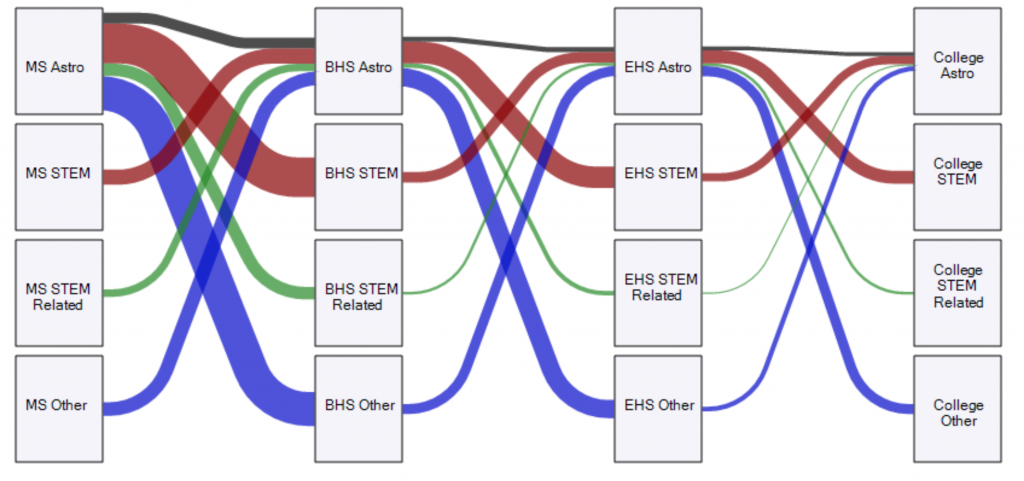

One of the team’s most interesting results is a visualization of the early leaky pipeline, shown below. It seems that most STEM fields lose future scientists after middle school. In particular, Astronomy attracts many students, many of which end up interested in other STEM fields. In this way, Astronomy is an important gateway for students interested in science!

Figure 1: An inflow & outflow diagram showing the evolving interests of all surveyed students. The black tube represents students who retain interest in astronomy, the red and green tubes represent students who flow between STEM fields (including Astronomy), and the blue tube represents students who flow between STEM fields and non-STEM fields.

The study connects interest level in Astronomy to the various activities students grew up with. It’s probably no surprise that being active in science programs, watching popular science programs and reading science fiction were all great indicators that a student would be interested in Astronomy in early high school, regardless of gender. Early participation in activities like math competitions also correlated with future scientific interests. Surprisingly, test scores, like the SAT, had no influence in students’ interest in astronomy. And remarkably, students who liked to take care of animals were significantly less likely to be interested in Astronomy!

The authors also considered the sexes independently, sharing important information about one of many underrepresented groups within astrophysics: women. Women were, across the board, less interested in astronomy at every stage of their schooling. However, they were more likely to be interested in astronomy if they had observed stars growing up! (This result was also true for men.) The authors emphasized that women are most excited about science when they can associate their personal identity with a STEM identity.

All of these interesting relationships are correlations — and they might not be causal. In fact, it would not be surprising if uncontrolled confounding variables (like socioeconomic status) were behind some of the uncovered trends. That being said, we can learn important lessons from this study: Share your love of Astronomy! The hard work that you put into reaching out to our community helps us grow and thrive by inspiring the next generation of scientists.