Title: The mass of the young planet Beta Pictoris b through the astrometric motion of its host star

Authors: I. A. G. Snellen & A. G. A. Brown

First Author’s Institution: Leiden Observatory, Leiden University, Leiden, Netherlands

Status: Published in Nature Astronomy, closed access

The mass of a directly imaged planet is a tricky quantity to measure. Normally all you have is the brightness of the planet in comparison to its host star. Since giant planets do not produce their own energy (e.g. through fusion like a star) they simply cool with time. Their initial brightness depends on their mass: the gravitational potential energy of all the material collapsing down to form the planet. Therefore, the brightness of the planet, combined with the age of the system and models of planet formation, can be used to back out the mass of the planet. A prominent question in the field of planet formation is the initial conditions for these models: how much of the gravitational potential energy goes into the planet (heating it up) and how much is dissipated before the planet forms? This uncertainty leads to a spectrum of different initial conditions ranging from “hot” to “cold” start models.

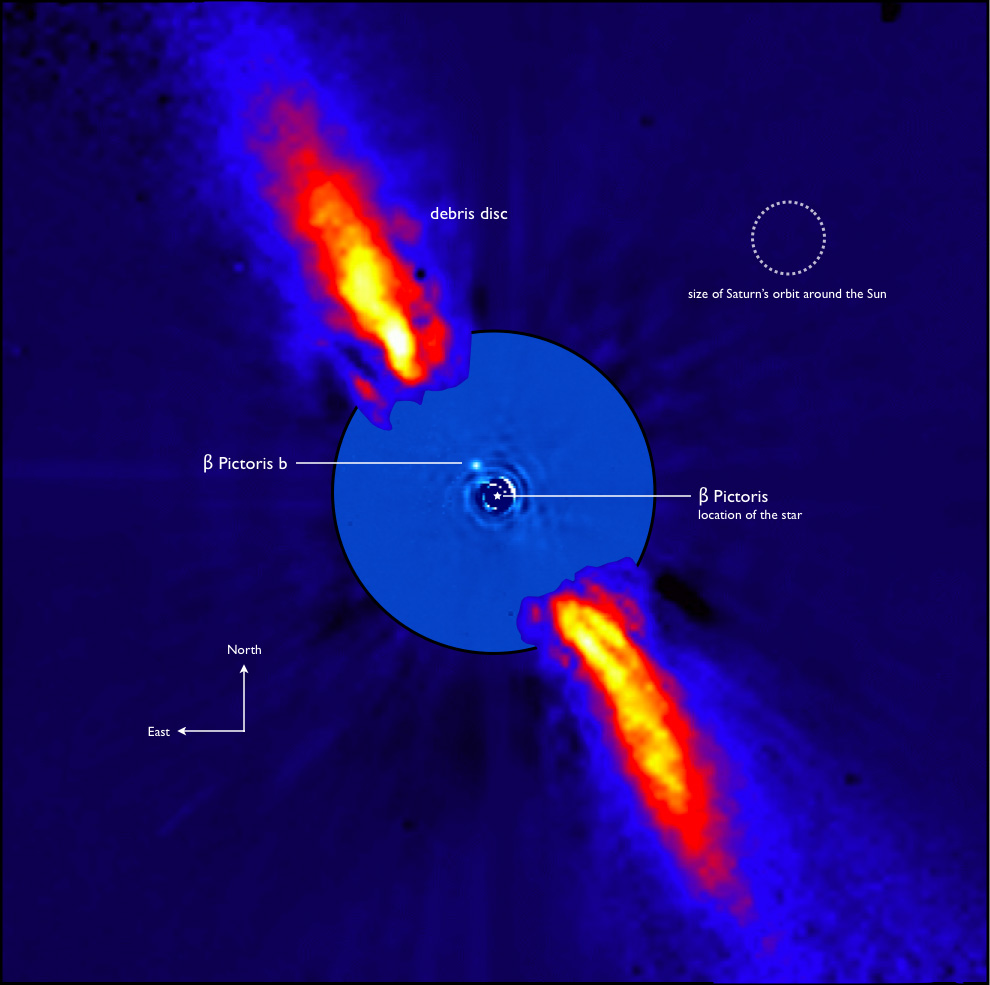

Figure 1: Left: Discovery image of β Pictoris b orbiting its host star inside a disk of gas and dust. Right: Animation of more recent data showing orbital motion of the planet.

Credit: (left) ESO/A.-M. Lagrange et al. (2009), (right) Jason Wang.

β Pictoris b is one of the first directly imaged planets. It is a gas giant (4-17 times the mass of Jupiter, though likely closer to 13) orbiting a nearby (19 pc) star in the young (~10-20 Myr) β Pictoris moving group. It has been well studied in the last decade since its discovery, including determining that its orbit is nearly edge on, though non-transiting. Figure 1 shows the first image of the planet and some more recent observations showing its orbital motion. Today’s paper presents the measurement of the mass of β Pic b using astrometry. Since the measurement is model independent, it can be used to calibrate the initial conditions of the models.

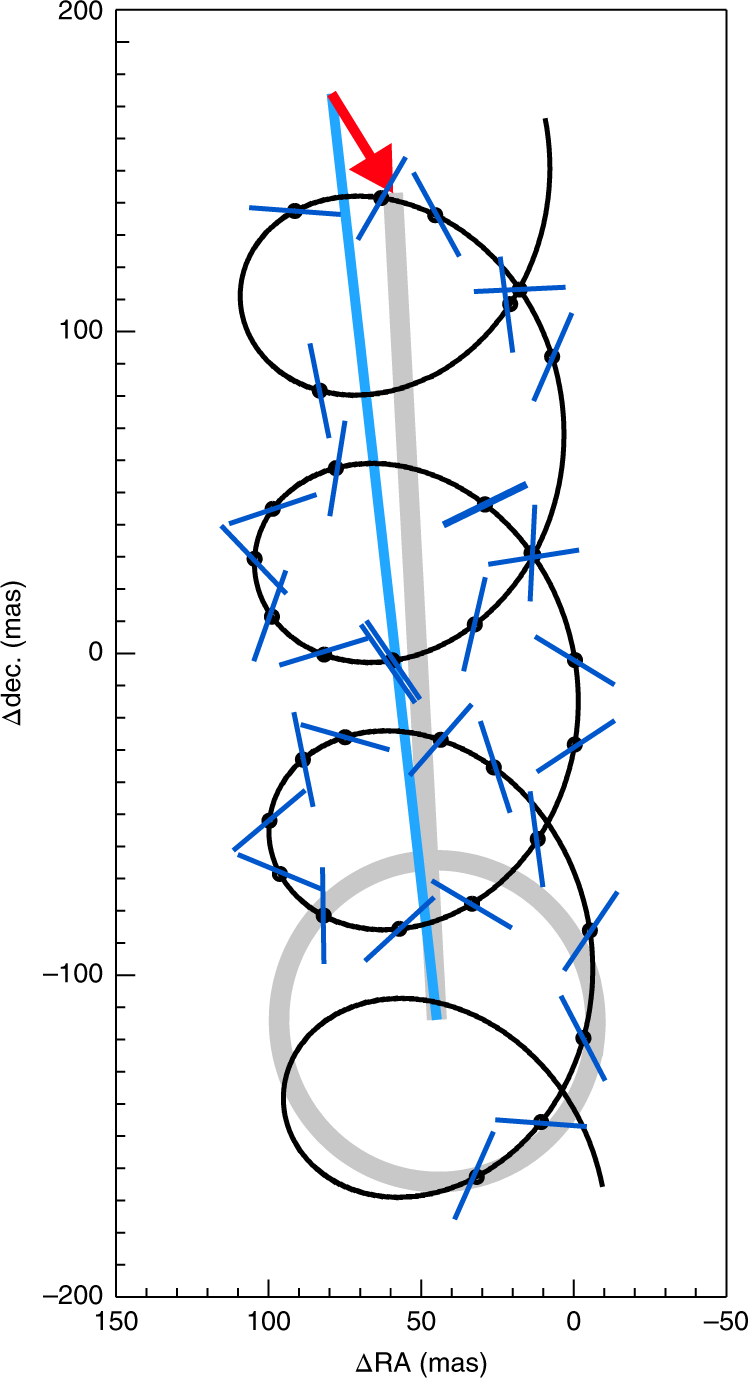

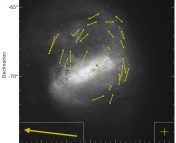

Figure 2: Hipparcos data from 1990-1993 showing the astrometric motion of β Pic. The black curve is the best-fit model to the parallax (shown by the gray circle) and the star’s proper motion (gray line). The light blue line shows the proper motion measured using the 24 yr Hipparcos–Gaia baseline, and the red arrow indicates the difference from the proper motion calculated using only the Hipparcos data. This difference, caused by the planet, is amplified by a factor of ten to make the effect visible. Figure 1 in the paper.

Astrometry is the precise measurement of the positions of stars and their motion. The dominant contribution to the apparent motion of stars is parallax (caused by the Earth’s yearly motion around the Sun) and the star’s proper motion (its 3D space velocity projected onto the plane of the sky). If the measurements are precise enough, it is possible to detect the much smaller reflex motion of the star orbiting the center of mass of the star and planet(S) (i.e. barycenter). The two most prolific space telescopes dedicated to astrometry are Hipparcos and Gaia, both run by the European Space Agency.

The authors of this paper leveraged the 24.25 years between the Hipparcos and Gaia measurements to precisely measure the proper motion of the host star, β Pic. The proper motion is simply the difference in the two position measurements divided by the time between them (with some small perturbation by the planet which is incorporated in the modeling). They then subtracted this motion from the 3 years of Hipparcos data to reveal the effects of the planet. Figure 2 shows this process. The amplitude of the star’s motion (Δθ) is the distance from the star to the center of mass of the system divided by the distance to the star (to convert to the angle on the sky). The equation is thus Δθ = (mp/M)*(apl/D), where mp is the planet’s mass, M is the mass of the star, apl is the size of the planet’s orbit, and D is the distance to the star. Fitting the specific data points is somewhat more complicated but uses a combination of Kepler’s laws and the center of mass equation to measure the planet’s mass.

While the inclination and position angle of the orbit of β Pic b are well constrained by the imaging data, the period is not (previously constrained to about 20-26 years). This is because all but one observation were taken when the planet was southwest of the star meaning that only about half the orbit has been observed. Luckily, astrometry can be used to constrain not only the mass of the planet but the period as well. Changing the period would shift the orbital phase at which Hipparcos observed β Pic, causing an acceleration or deceleration in the observed motion. Since the proper motion observed by Hipparcos was approximately constant over its 3 years of data the period of β Pic b must be 22-30 years. Combining this limit with constraints from fitting the orbit using imaging data, β Pic b has a mass of 11±2 Jupiter masses and a period of 24-26 years.

This mass measurement is consistent with the “hot start” models of planet formation, suggesting that much of the gravitational potential energy of the material which formed the planet was retained and not dissipated during accretion. This points towards gravitational collapse within the disk rather than core accretion being the formation mechanism of β Pic b. In the future, as Gaia builds up more data, measurements like this will be commonplace and up to an order of magnitude more precise. We are on the verge of moving from the era of lower limits on exoplanet masses (provided by the radial velocity technique) to absolutely measured exoplanet masses.

Very interesting article. I have a few questions, but first, at the end of the third paragraph the sentence cuts off and is incomplete.

In the beginning you state that the planet doesn’t produce its own energy but its initial brightness depends on its mass. This brightness is just us to thermal energy, which we would see as infrared?

Lastly, would not accretion lead to gravitational collapse and compression thereby generating thermal energy? Aren’t these two processes linked together?

Thanks!

The initial brightness we see is thermal black body radiation (with signatures of the atmosphere imprinted on it). For the typical temperatures of these planets, this radiation peaks in the infrared.

Rather than thinking of generating thermal energy, think about converting gravitational potential energy into thermal energy, which is slowly radiated away. Two ways we think planets form are core accretion and gravitational collapse. In the core accretion scenario, dust clumps together to form pebbles, pebbles clump to form boulders, et cetera until the planet is massive enough to start accreting gas. Eventually it reaches an isolation mass where the planet has cleared the area around it and cannot “feed” anymore. This process takes a long time so much of the gravitational energy in the dust/pebbles/boulders and gas is dissipated and does not heat up the planet. The gravitational collapse scenario is similar to how stars form but it takes place in the protoplanetary disk. This process is relatively fast so the planet retains most of the energy and starts hotter.

Here are a few relevant astrobites:

https://astrobites.org/2017/09/13/can-gas-giant-planets-form-through-pebble-accretion/

https://astrobites.org/2015/09/15/triggered-fragmentation-in-self-gravitating-disks/

https://astrobites.org/2011/02/28/planet-formation-at-wide-orbits-through-gravitational-instability/

Thanks very much! It’s agonizing that these processes take so long. If we only had a time machine! 😉

Please provide references towards that equation or ratio for determining the mass of the planet or general orbiting body.

The equation I gave comes from the size of the star’s orbit around the barycenter (m1*a1=m2*a2, where 1 is the star and 2 is the planet). You simply solve for a1 then divide both sides by the distance to convert to the angular size of the orbit. A more detailed overview can be found in section 8 of Debra A. Fischer’s chapter in the Protostars and Planets VI book here: https://arxiv.org/abs/1505.06869