In this series of posts, we sit down with a few of the keynote speakers of the 234th AAS meeting to learn more about them and their research. You can see a full schedule of their talks here!

‘Our job is to think our way to the Moon and back’. The twelve words on the job advert that changed the course of Prof. Jim Head’s career. This was 1968 and armed with a PhD in geology, Prof. Head joined the Apollo space program to help realise President Kennedy’s dream of sending humans to the Moon.

Prof James Head III, Brown University

James Head III is the Louis and Elizabeth Scherck Distinguished Professor in the Department of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences at Brown University. Growing up in Washington DC in the 1940s and 50s, Prof. Head was always looking at the ground, fascinated by the rocks beneath our feet. This led him to study geology at both undergraduate and graduate levels. However, this was the era of the Space Race and something caused him to look up. In 1957, with his ‘internet’ actually a shortwave radio, he used the timings sent by Radio Moscow to hear the characteristic ‘beep, beep, beep’ that signalled the first manmade satellite, Sputnik 1, passing overhead.

Another major influence on Prof. Head’s career was one of his professors in grad school. This ‘far-thinking’ professor taught a course on remote sensing techniques, allowing them to apply what they had learnt about geology on Earth to look at other planets. After gaining his PhD from Brown University, Prof. Head was looking through the university’s job catalog, where he came across that influential job advert.

While the primary goal of Apollo was to send people to the Moon, those working on the missions realised the scientific opportunity. Working for NASA, Prof. Head helped select landing sites for the Apollo missions that maximized both safety and scientific merit. He trained (and continues to train) astronauts in geological techniques and surface exploration. He helped select experiments for the Moon and analysed the returned lunar samples. While the Earth has evolved due to its dynamic atmosphere, oceans and continents, the barren, airless Moon is comparatively preserved, allowing geologists to study the formative years on the Moon and fill in the missing record on Earth.

Current and future exploration of the Moon

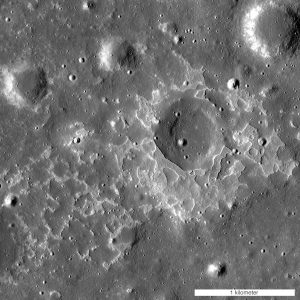

After working at NASA, Prof. Head returned to Brown University. He continues to work on both lunar and planetary geology. He is involved with the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) mission, launched as part of President Bush’s vision to go back to the Moon. The LRO has been surveying the Moon for nearly 10 years, gathering data on its topography and mineralogy. The LRO’s Lunar Orbiter Laser Altimeter uses a laser to bounce light off the Moon, timing how long the echo takes to measure the height of the Moon’s surface. The topographical data it collects can be used both for identifying landing sites and to inform our understanding of the Moon’s geological past. A surprising result from the LRO is the very unusual nature of numerous IMPS. While small and pesky to explain, these are in fact Irregular Mare Patches, unusual depressions, often with mounds, on the Moon’s surface. Some geologists have hypothesised that IMPs are incredibly young, perhaps under 100 million years old. If they are due to volcanic activity, this would mean rewriting our understanding of the Moon (as volcanic activity was believed to have ceased 1 billion years ago).

Figure 1: An example of an Irregular Mare Patch or IMP, a depression within the lunar mare (the dark flat planes mistakenly identified as seas by early astronomers). Image Credit: NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University.

One place that Prof. Head would like to explore further is the South Pole Aitken Basin, caused by the oldest known impact on the Moon. This provides a ready-made drill hole, allowing us to sample the mantle below the Moon’s crust and date the material. This is the landing site of Chang’e 4, the first mission to land (rather than crash) on the far side of the Moon, and part of the Chinese series of missions which Prof. Head has helped advise on. A future possible mission, Chang’e 6, may return a sample from this region.

While some believe that the next destination of human space exploration should be an asteroid or Mars, Prof. Head quotes the Apollo astronauts as saying, ‘We made going to the Moon look too easy’. He believes that the Moon would act as a good training base for astronauts on missions to Mars. Prof. Head explains, ‘We took the Apollo astronauts out to different places on the Earth’s surface, from Hawaii to Iceland, all over the world to train them in different geology. The next wave of astronauts will go to the Moon to learn how to do activities as they are training to go to Mars.’ Training on the Moon would allow us to learn how to explore another world again just a few days space travel from the safety of Earth before committing to the hundreds of days required to reach Mars.

While the Moon acts as a useful museum for Earth’s earlier history, studying geology on Earth can inform our understanding of other, more distant, planets. Studying the very cold and dry Antarctica is an analog for an earlier, wetter Mars and could help us understand how channels on Mars’ surface formed and perhaps how Mars evolved into the cold, dry rock we see today. Studying Antarctica is also important for understanding climate change. Since summer in Antarctica has highs of a few degrees above freezing, a small increase in temperature can have large effects on how much ice melts. Prof. Head has a black volcanic rock from Antarctica, with what appeared to be deep drill holes in. In fact, these holes occur naturally; falling snow melts, and gets into the pores of the rock. Prof Head worked out that over time this forms the deep holes by noticing that snow landing in the holes melted faster. This is one example of how being able to observe these processes in action on Earth can allow us to piece together how similar looking rocks we see today on Mars may have formed.

Advice for students

What advice does Prof. Head have to students about to start their careers? ‘Don’t be afraid to leap into the not very well known’, he says, and to seize an opportunity even if it seems beyond your capability. He points out that we do not know everything, that ‘none of us were qualified to plan the lunar landings’, and reassures us that ‘it is ok to have a non-linear career path’.

More generally, Prof. Head is an advocate for daydreaming, which is difficult in this age of iPhones and distractions, but is ‘really important to let the mind make seemingly random associations’. He suggests to plan your day to not let the schedule of others stopping you do what is most important. And finally, be ‘passionate about what you do’.

Find out more at Professor James Head III’s plenary talk, ‘The Apollo Lunar Exploration Program: Scientific Impact and the Road Ahead’ on Thursday 13th June at 12:20 PM at #AAS234.