This post was written with significant contributions by Astrobites author Gourav Khullar. Authors Meredith Rawls and Mia de los Reyes provided valuable input.

Author’s Note: This post is part of our series on interactions between predominantly-western astronomy and Indigenous communities around the world. Other posts in the series so far: Hawai`i, North America. The majority of the research for this article has been done via sources written in English. A future piece detailing the experiences of Indigenous Chileans through their perspectives is in preparation.

Chile has some of the best conditions in the world for observing the night sky. Indigenous communities in the Atacama Desert, located in the northern part of what is now Chile, engaged in astronomy as a significant part of their culture and survival, long before Chile became a hub for modern telescopes. Much of this Indigenous astronomical knowledge was destroyed by the conquest and colonization of Indigenous land, which subsequently led to Chilean skies being observed and controlled primarily by Western astronomers in recent decades. Some observatories in Chile now have programs to document this knowledge and engage locals in astronomy, but modern Indigenous communities continue to fight for the rights to their history and their land. This astrobite provides an overview of Chilean Indigenous communities, Western-led astronomy in Chile, and the publicly documented relationship between the two.

La Silla observatory, the first Western-led telescope constructed in Chile, and the clear skies of the Atacama Desert. Source: ESO/José Francisco Salgado

The Indigenous Communities of Chile

Indigenous groups on the land that is now Chile can be traced back at least 10,000 years, but now make up only 9% of Chile’s population. The largest group, the Mapuche, make up 85% of the Indigenous population and are located primarily in the southern part of the country. The Indigenous communities of the Atacama Desert, where most observatories are located, consist of separate cultures but are collectively known as the Atacameños or the Likan Antai; they now make up 3% of the Indigenous population. In the 15th century the Atacama was conquered by the Incans, and in the 16th century the region was again conquered by the Castillians (from what is now Spain), after significant resistance by the Likan Antai people. After centuries of rule by Spain, and later by Peru and Bolivia, the Atacama was taken over by Chile in 1883. Today the region is still controlled by the Chilean state, with some national reserves co-managed by the government and Indigenous groups.

Chile has a history of oppression against Indigenous communities, both in the colonial era as well as during the dictatorial regime of Augusto Pinochet beginning in the 1970s (see here, here and here to read more about Pinochet’s atrocities and their aftermath in Chile). In particular, the state engaged in the acquisition and reselling of land to foreign entities, granting them extraterritorial jurisdiction and diplomatic immunity without prior consent of its original inhabitants (often considered a form of colonialism; see here, here, here and here). For example, in the 1990s, the European Southern Observatory faced land and labor conflicts at Cerro Paranal (home of the Very Large Telescope), and enjoys extraterritorial governance at the observatory sites Paranal and La Silla.

Indigenous people in Chile, including the Likan Antai, continue to face high rates of poverty and systemic discrimination. They are working to recover their ancestral knowledge and rights to natural resources, including water and land—which Chile has provided to, among other entities, Western astronomical institutions.

The Growth of Western Astronomy in Chile

In 1962, the European Southern Observatory (ESO), a Europe-based organization for international astronomy, chose the edge of the Atacama Desert as the location for new astronomical observatories. They negotiated with the Chilean government for 250 square miles of land near the city of La Serena (along with exemption status from taxes, environmental regulations, and Chilean labor laws). The La Silla Observatory was inaugurated in 1969, and three telescopes were constructed there by ESO in the ensuing two decades.

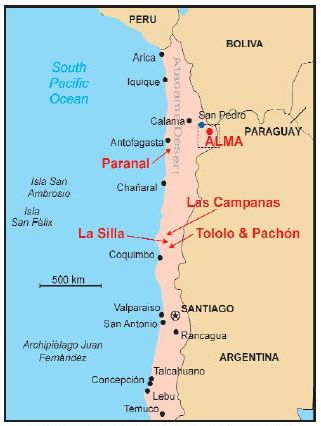

The locations of the internationally run observatories in Chile. Source: NRAO

Meanwhile, the American consortium AURA developed the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory starting in 1962. Throughout the 20th and early 21st century, Western astronomy continued to expand its presence in the Coquimbo and Atacama regions of Chile. These used to be home to a small Indigenous population, at least hundreds of years before the Spanish conquest of the area. The Diaguita people, which refers to multiple cultures in the region, numbered around 30,000; however, their population was decimated by the conquistadors after they rebelled.

There are now around 90,000 Diaguitas in Chile, but their population was sparse near the telescope sites by the time of their construction; there is no documented interaction between them and Western astronomers as they built new observatories. The US-based Carnegie Institution for Science constructed Las Campanas Observatory in 1969; ESO built Paranal Observatory in 1988, which became the site of the Very Large Telescope (VLT); and AURA constructed the Gemini South Observatory in 2002. While these observatories now operate public outreach and local education programs, none of them explicitly engage with Indigenous communities.

ALMA and Local Indigenous Communities: A Better Model?

The most recent (completed) large observatory in Chile is the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA). The radio interferometer, which consists of 66 telescopes on the Chajnantor plateau in the Atacama, saw first light in 2011. Unlike previous observatories, the construction of ALMA involved communication with the local Indigenous people, the Likan Antai. One point of contention was the preservation of archaeological sites along the planned access road to Chajnantor; the road was built to avoid these, and an educational site museum was constructed, but it remains a sensitive issue.

The remains of an Indigenous town along the access road to ALMA were reconstructed and turned into a museum. Source: ALMA/ESO

Upon the completion of the telescopes, a group of Likan Antai people performed a ceremony for the new observatory, asking Mother Earth for blessings for the ground upon which the telescope is built and for the local people. Representatives from the Likan Antai community were also present at the ALMA inauguration.

Likan Antai people performing a traditional ceremony for the construction of the ALMA telescope on Chajnantor. Source: ESO

Despite the presence of this leading scientific site, the nearby communities had lower educational achievement than the rest of Chile; the gap was even more pronounced for local Indigenous students. The Sister Cities organization began to connect local students with the opportunities presented by ALMA. Through the program, students from a nearby high school, most of whom belong to the Likan Antai community, engage in radio astronomy research as well as an ethnography project on the astronomical practices and cosmic vision of the Likan Antai.

ALMA has also worked with local scientists to learn more about early Indigenous practices. Jimena Cruz, a Likan Antai anthropologist from San Pedro de Atacama, collaborated with ALMA astronomers to understand the significance of rock pillars constructed by the Incas throughout the desert. They found that the pillars aligned with the location of the sunrise on the summer and winter solstices, adding to the understanding of Incan astronomical and cultural practices.

ALMA further collaborated with Cruz and other researchers at the San Pedro Museum to preserve the Likan Antai cosmic worldview. They found that the Likan Antai had an extensive vision of the cosmos based on observations of the sky as well as their local geography, making them the oldest astronomers in the Atacama. This is evidenced by the name of the high-altitude plateau that ALMA is built on: Chajnantor means “place of lift-off” in Kunza, the ancestral language of the Likan Antai. ALMA has also sponsored initiatives to document and recover the Kunza language, which was banned at one point and now has no native speakers.

Alongside ALMA’s outreach efforts to local Indigenous communities, the observatory has had an at-times tenuous relationship with the mostly local Chileans who work on site. In 2013, 80% of the workers went on strike for better work conditions and pay. They cited the strenuous conditions of working at high altitude, long 12-hour shifts, and inadequate sanitation. After 17 days the labor union reached an agreement with ALMA, but some grievances are more deeply rooted. The international employees at Chilean observatories are often granted privileges by the government such as tax-exempt status, while Chileans are not. The observatories are also not subject to labor inspections, unlike Chilean businesses, potentially allowing for poor work conditions like those that occurred at ALMA. Both local Chileans and Indigenous communities continue to fight to benefit from, and not be taken advantage of by, the practice of Western-led astronomy in Chile.

The Future of Astronomy in Chile

While ALMA and some other observatories are making efforts to collaborate with Indigenous communities and incorporate Indigenous culture into their work—the VLT named its unit telescopes after Mapuche names for objects in the night sky, for example—other telescopes and organizations have not made such efforts. La Silla and Las Campanas observatories, and their associated programming, do little to publicize the history of Indigenous peoples or their erasure during colonial times and by the Pinochet regime.

Astronomy continues to expand in Chile, with significant Western influence and backing. The US-funded Large Synoptic Survey Telescope is under construction on Cerro Pachón in northern Chile, with first light planned for 2020 and the main decade-long survey beginning in 2022. The Extremely Large Telescope is being developed by ESO on Cerro Armazones in the Atacama, and with a goal of first light in 2025. Construction of the Giant Magellan Telescope, led by the US, is underway at the Las Campanas Observatory, also planned to begin in 2025. None of these under-construction observatories have yet engaged in communication with Indigenous groups or announced outreach around Indigenous history and culture.

Questions remain about the relationship between these observatories and Indigenous groups, as well as Chileans more broadly. On the scientific side, Chilean astronomers have typically been allocated 10% of the observing time on internationally developed telescopes. However, some argue that this is not sufficient; observatories in Hawai’i and the Canary Islands, for example, grant 15% and 20% of observing time to local astronomers, respectively. This time allocation applies to astronomers and graduate students at Chilean institutions. However, this system doesn’t distinguish between Chilean-born astronomers and foreign astronomers working in Chile, and doesn’t prioritize Chileans of mestizo or Indigenous heritage.

These observatories present opportunities for Western astronomical institutions to continue working with Indigenous communities, as well as Chilean astronomers and local communities. The efforts described here to restore Indigenous sites and culture, provide educational opportunities to local communities, and document Indigenous astronomical practices are models that can be built on to ensure that Indigenous communities are centered in and benefit from the practice of astronomy in Chile.

Congratulations on an excellent article that sheds a light on indigenous cultures and astronomy which gives rise to tensions in many countries. Well done