The undergrad research series is where we feature the research that you’re doing. If you’ve missed the previous installments, you can find them under the “Undergraduate Research” category here.

Are you doing an REU this summer? Were you working on an astro research project during this past school year? If you, too, have been working on a project that you want to share, we want to hear from you! Think you’re up to the challenge of describing your research carefully and clearly to a broad audience, in only one paragraph? Then send us a summary of it!

You can share what you’re doing by clicking here and using the form provided to submit a brief (fewer than 200 words) write-up of your work. The target audience is one familiar with astrophysics but not necessarily your specific subfield, so write clearly and try to avoid jargon. Feel free to also include either a visual regarding your research or else a photo of yourself.

We look forward to hearing from you!

************

Linnea Wolniewicz

University of Colorado, Boulder

Linnea Wolniewicz is a third-year undergraduate student at the University of Colorado, Boulder studying Astrophysics. She completed this research at the University of Hawaii’s REU program under the supervision of Dr. Daniel Huber and graduate student Travis Berger. She will be presenting her work via an oral presentation at the 237th AAS meeting in January, and plans on submitting it for publication in the Astrophysical Journal.

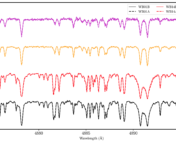

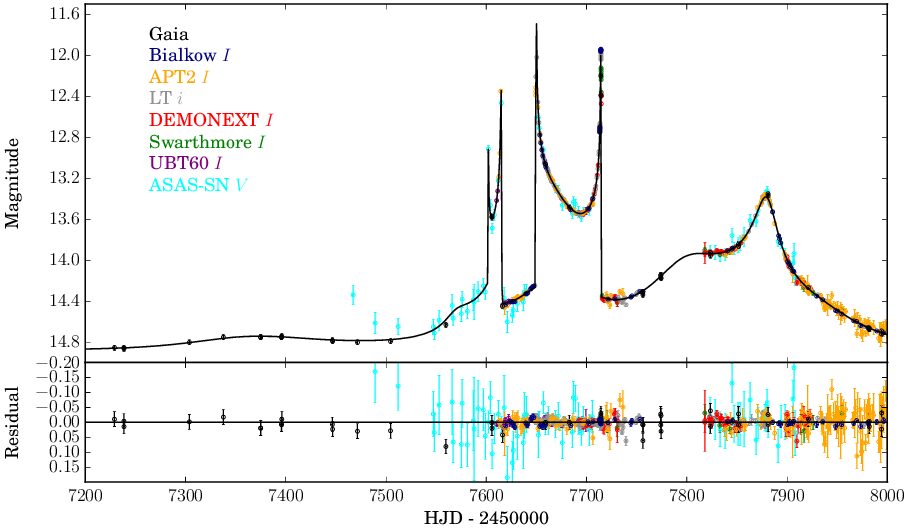

The Kepler space telescope revolutionized exoplanet science and stellar astrophysics by observing 200,000 stars over 4 years. However, an important piece of information needed to exploit the Kepler data is its selection function (a function to determine which stars in its field of view are observed), as Kepler could only observe a small fraction of the stars targeted by its detectors. My research addresses the question of whether Kepler’s selection function was biased with respect to evolutionary state, binarity, or kinematics (proper motions) of the target stars. I address this question by using Gaia DR2 to reconstruct the Kepler selection function and explore any of its possible biases. I find that Kepler was complete (i.e. observed all stars up to some brightness/magnitude threshold) for the brightest stars (those with Kepler magnitudes, a measure of brightness with respect to the Kepler telescope, < 14 mag), and was effective at observing the solar-type stars it was launched to find. The first few dark panels of Figure 1 affirm this conclusion, as it can be seen that Kepler observed most stars brighter than Kp = 14 mag. I also find that Kepler was unbiased with respect to kinematics, but that it was biased against binarity as it systematically selected non-binary star systems for observation.

If you are an undergraduate that took part in an REU this summer and would like to share your research on Astrobites, please contact us at [email protected]!