Title: Recovering the origins of the lenticular galaxy NGC 3115 using multi-band imaging

Authors: Maria Luisa Buzzo, Arianna Cortesi, Jose A. Hernandez-Jimenez, Lodovico Coccato, Ariel Werle, Leandro Beraldo e Silva, Marco Grossi, Marina Vika, Carlos Eduardo Barbosa, Geferson Lucatelli, Luidhy Santana-Silva, Steven Bamford, Victor P. Debattista, Duncan A. Forbes, Roderik Overzier, Aaron J. Romanowsky, Fabricio Ferrari, Jean P. Brodie, Claudia Mendes de Oliveira

First Author’s Institution: Universidade de São Paulo, IAG, Rua do Matão 1226, Cidade Universitária, São Paulo 05508-900, Brazil

Status: Accepted for publication in MNRAS [closed access]

Galaxies come in all shapes and sizes–round, disky, smooth, spiraled, or even shaped like penguins! The two most commonly-mentioned types are spirals and ellipticals, but there also exists an intermediate between the two: the lenticular galaxy, which has a disk and a bulge like spirals, but does not have grand spiral arms. Over the years, astronomers have worked to not only classify galaxies based on their morphology, but also to understand how they form and evolve over time. While spirals and ellipticals are well studied, lenticular galaxies have one of the most enigmatic formation histories of the different galaxy types. The authors of today’s paper take on the role of galactic detectives as they try to piece together the narrative of NGC 3115, the closest lenticular galaxy to our Milky Way.

Galactic Building Blocks

The authors compiled data of this galaxy in 11 filters, stretching from the ultraviolet to the infrared. This data came from different observatories, since no single telescope exists that can image in such a broad range of wavelengths. They fed these images into a tool called GALFITM in order to do a multi-wavelength decomposition of the galaxy into different structural components. Let’s step back and talk about what that previous sentence actually means.

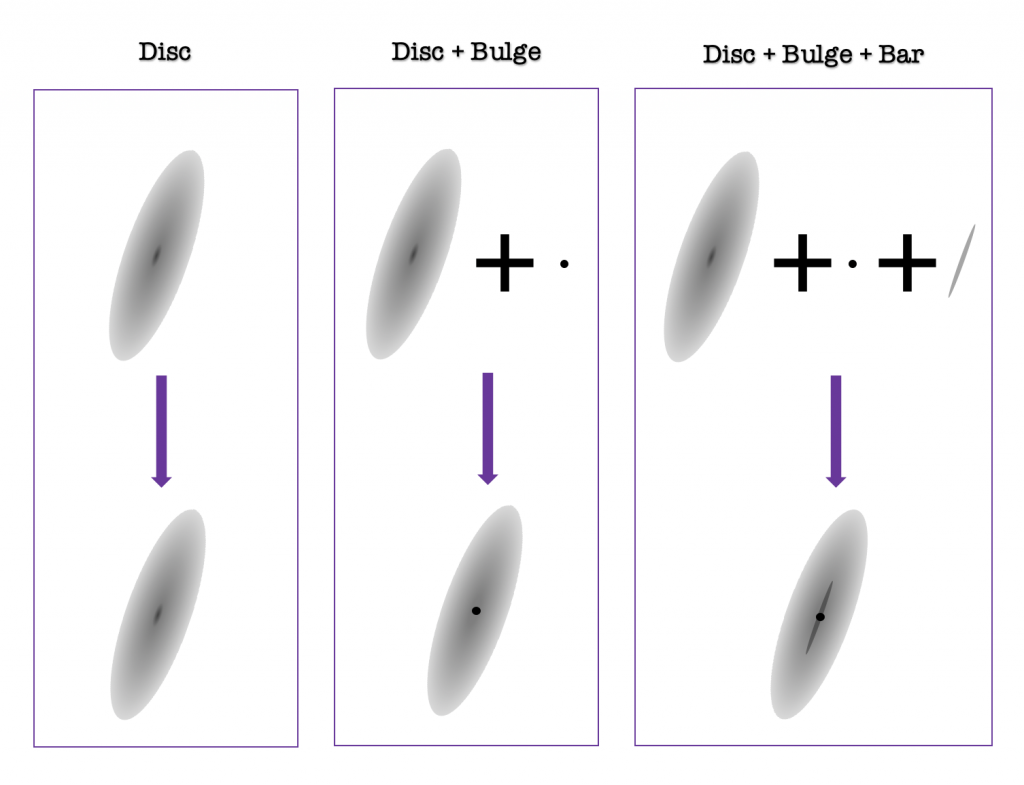

Say you wanted to make a sandwich. Most sandwiches are composed of different appetizing building blocks that can be mixed and matched–bread, tomato, mayo, etc. But there are many types of sandwiches, with different ingredients and proportions. A classic BLT has white bread, lettuce, tomato, bacon, and mayonnaise, while a Reuben uses rye bread, corned beef, cheese, sauerkraut, and dressing. You can also make variations on sandwiches by changing the amount or variety of ingredients (for example. sourdough vs rye bread). Galaxies are also all composed of common galaxy-building features, but the features differ depending on their type. Some galaxies can be modeled as one disc, others could be the composition of multiple discs, a bulge, and spiral arms, each with different parameters. This is exactly what GALFITM tries to do, simultaneously using a collection of multi-wavelength images of the same galaxy to figure out what components the galaxy is made from. It takes each parameter of a component, such as its radius and Sérsic index, and fits that value into a wavelength-dependent polynomial. All the program requires from us is initial parameters to use as a launchpad to find the best model of the galaxy: how many components there are, the order of the polynomial, which tells us how much we’re letting that parameter change with wavelength, and the initial conditions (magnitudes, radii, etc.).

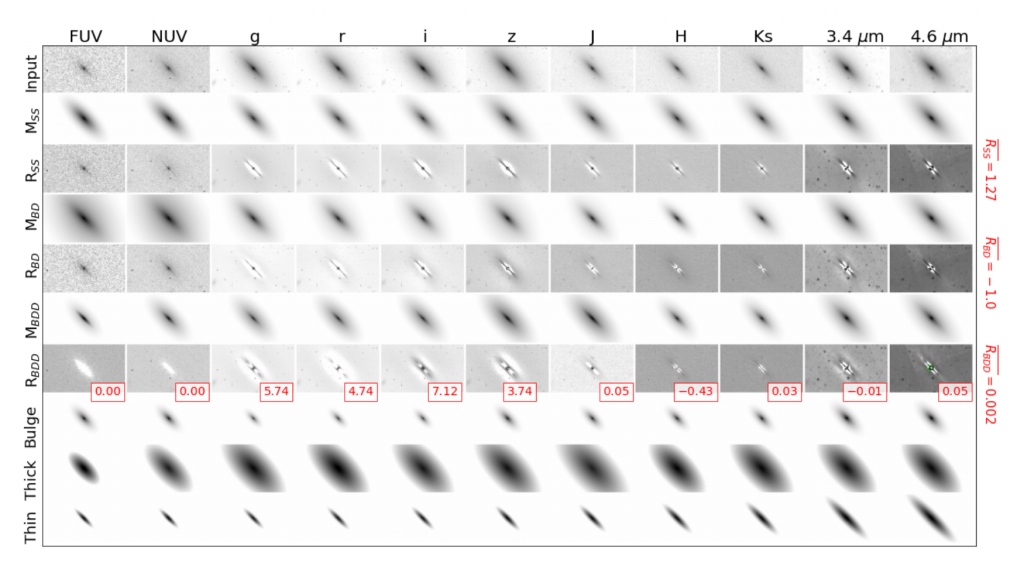

Fitting galaxies is tricky because you have to achieve a balance between leaving parameters free to vary and putting constraints on some components so that your final model is not nonphysical. You can then tell which models are best by looking at a residual image (original minus model). If the model describes the galaxy perfectly, the residual should be completely smooth. After running thousands of models with different variations, the authors found that NGC 3115 is best described by three components, a bulge and two discs, which they interpret as a classical bulge, thin disc, and thick disc. They also found evidence of a faint bar and spiral arms.

Too Blue to be True

Going back to our analogy, given a sandwich, it might be hard to tell how fresh the ingredients are–unless the lettuce is completely wilted or the bread is moldy, it’s usually difficult to differentiate a sandwich made from fresh ingredients to ones lying in the fridge for a few days. Just like it can be hard to tell the freshness of ingredients over a short timespan, astronomers also have the difficult task of piecing together formation histories of galaxies from a single snapshot–we can’t wait a million years to see how galaxies evolve over time. So now that they successfully built NGC 3115, the authors honed in on different parameters of its features to weave together its history. They examined the variation in color along the galaxy’s major axis and found that in the ultraviolet, the inner region of the galaxy is bluer than the outer region, with strong emission in the infrared and x-ray as well. The authors postulate that this could be due to a young stellar population in the bulge, AGN activity, or a mix of both. In order to resolve this puzzle, they use a spectral energy distribution (SED) fitting code to extract the physical properties of NGC 3115’s components. This technique aims to model how much energy the galaxy emits at different wavelengths, which can be compared to observed SEDs to extract properties of a galaxy such as its mass or star formation history (SFH). Running millions of models with different SFHs, the authors found that whether or not they included an AGN component in the bulge as part of their model, this component was always lower luminosity and subdominant to stellar emission, so they suggest that the blueness of the bulge cannot be due to AGN activity and therefore the galaxy should have undergone recent star formation.

Close Encounters of the Starburst Kind

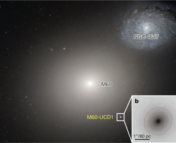

NGC 3115 also has many globular clusters and several ultra-compact dwarf companion galaxies. To see if these affected NGC 3115’s evolution, the authors modeled one of them, KK084, and extracted its physical properties using a Python library. They found that KK084’s colors were very different from NGC 3115 itself, indicating that the two have different stellar populations. A new stellar population in the dwarf could have been caused by an encounter with NGC 3115, which would cause new star formation, but KK084 is too faint for us to prove or disprove this from modeling alone. So the authors tested this hypothesis by looking for an offset in NGC 3115’s core, which would be further evidence of a recent interaction. They found that NGC 3115’s core indeed is displaced relative to its external parts, indicating that it encountered a companion a few hundred thousand years ago, with KK084 being a good candidate. This would also help explain the faint bar and spiral arms they found when modeling the galaxy.

Hello, My Name is NGC 3115

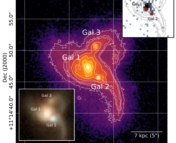

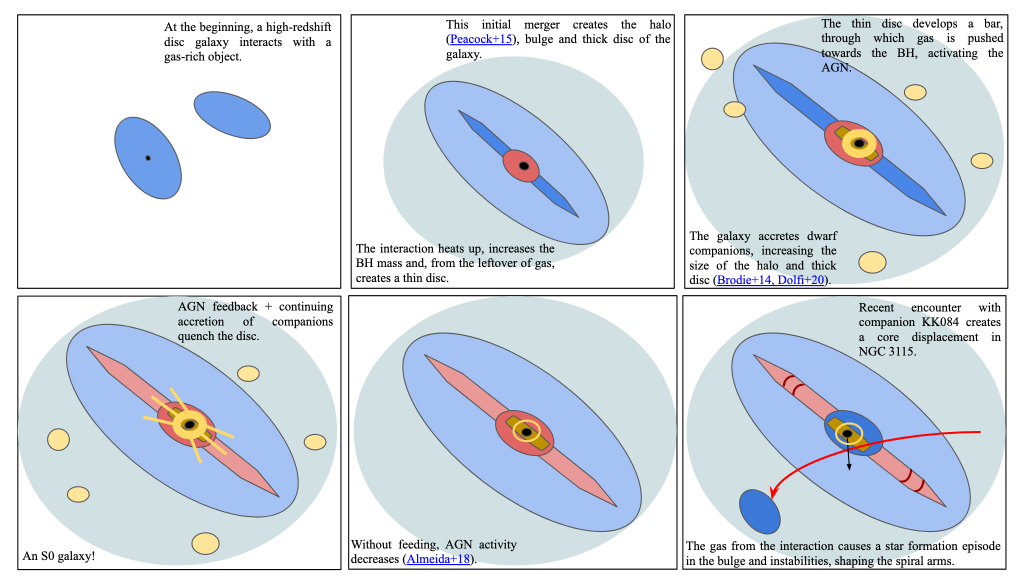

All of the clues that the authors and previous astronomers gathered finally helped them piece together a formation history of NGC 3115, which is illustrated in Figure 3. Most likely, NGC 3115 formed from a gas-rich merger, forming the bulge and thick disc. Then through processes of accretion and feedback, a thin disc developed and an AGN was activated, which quenched star formation due to the influx of hot gas that prevented cooling. After star formation had basically stopped, the AGN had nothing to feed off of, so it too died down. But then a companion galaxy like KK084 interacted with NGC 3115, causing a rejuvenation in star formation from the influx of new gas, causing NGC 3115’s core to become displaced and spiral arms to form.

We can uncover the building blocks of what make up the galaxy, and also learn about its physical properties that can give us hints about when it formed stars or got its shape. Combined with archival data from surveys, analyses like these will continue to aid us in understanding galaxy evolution as a whole, and enable us to recover a chapter of our universe’s history.

Astrobite edited by Wynn Jacobson-Galan

Featured image credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/Univ. of Alabama/K. Wong et al; Optical: ESO/VLT – http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/chandra/multimedia/photo-H-11-248.html