Title: Intracluster Magnetic Filaments and an Encounter with a Radio Jet

Authors: L. Rudnick, M. Bruggen, G. Brunneti, et al.

First Author’s Institution: University of Minnesota

Status: accepted for publication in ApJ

The intracluster medium is wracked with the battle scars left behind over the history of a galaxy cluster: cavities, shocks, sound waves, radio lobes. The blast zones of relativistic jets, the fronts left behind by the imperial ambitions of galaxies, all are etched onto the intergalactic landscape. But there is an order to this chaos. Out of the fog, long and slender networks of filaments coalesce, lit up by flows of charged particles like neurons of a vast cosmic brain.

These filaments are thought to be a natural consequence of turbulence in plasma with a high ratio of gas pressure to magnetic pressure. A weak magnetic field can be strengthened exponentially several orders of magnitude by turbulent motion on large scales, such as the sideswipes and collisions of galaxies. Sheets of electric current are torn apart by the churning of the plasma sea, forming bundles of fibers. The fibers’ fields strengthen as they are stretched by the shearing motions until the entire galaxy cluster is draped in magnetic noodles.

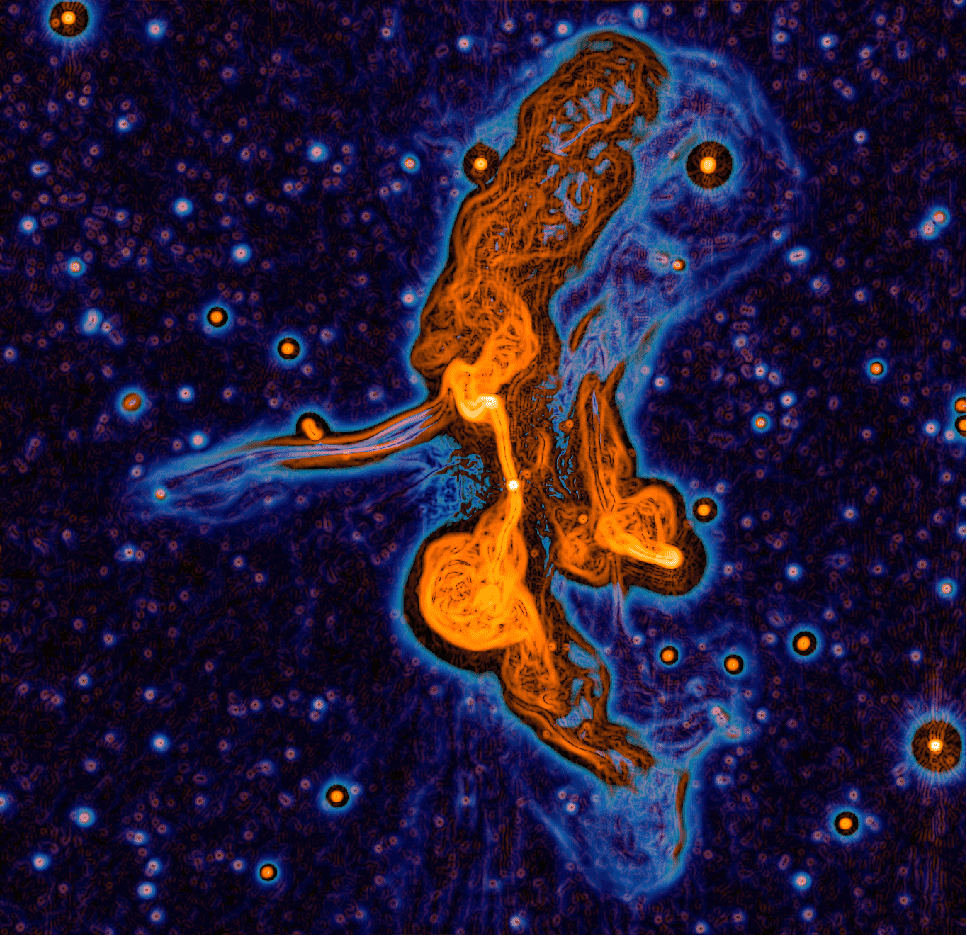

One such galaxy cluster, the cluster Abell 194, is shown in Figure 1. Today’s paper uses radio and X-ray observations to map out a particular subset of the cluster’s filaments, and their interactions with a supermassive black hole’s fury.

A Cluster Wracked by Extremes

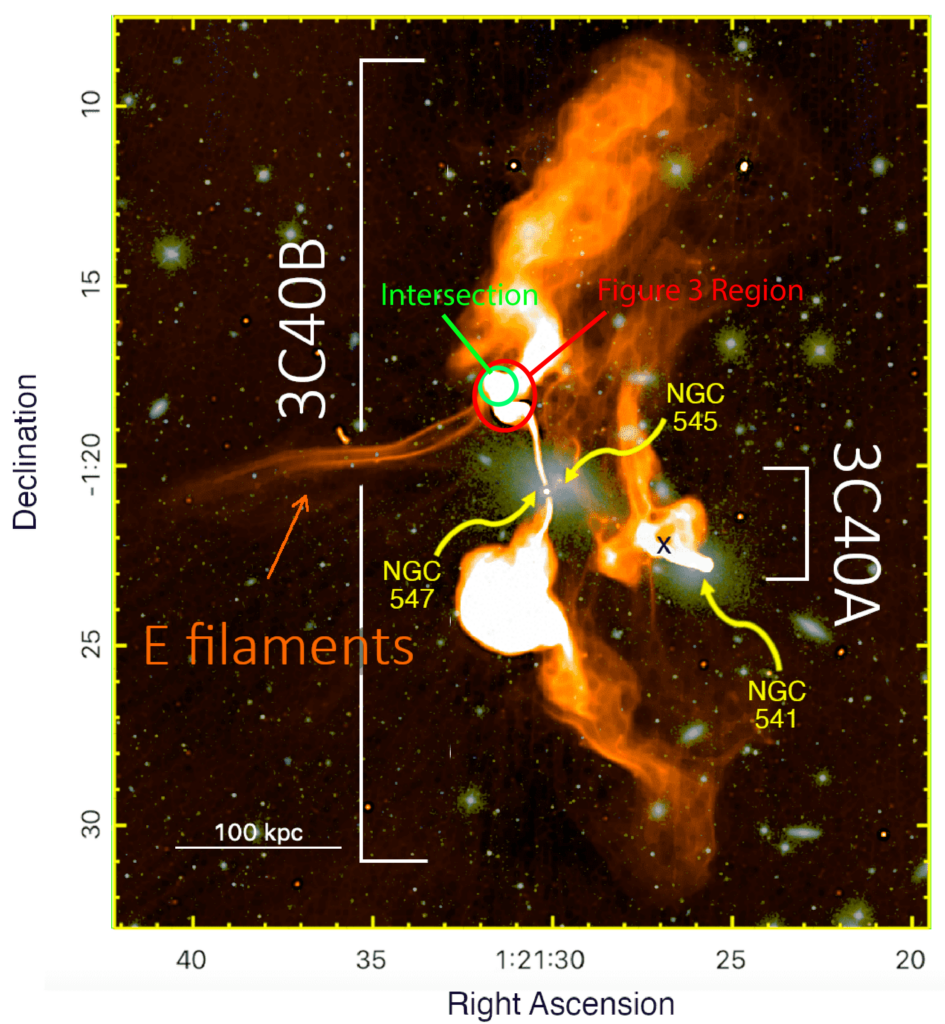

Abell 194 is a galaxy cluster containing a pair of interacting galaxies, 3C40A (aka NGC 541) and 3C40B (aka NGC 547), shown in Figure 2. As the two galaxies draw closer together under their mutual gravity, gas is dislodged from its usual orbits, spiraling into the waiting maws of their supermassive black holes. The resulting jets billow out across millions of light years, radio waves whispering of powers terrible and gross. The two galaxies’ violent ejections have a huge impact on their surroundings, filling the cluster with cosmic rays and triggering a starburst where 3C404A’s jet collides with another galaxy. The jets’ impact also is felt in the intricate web of magnetic filaments threading the galaxy cluster. Two 650,000 light-year-long strands in the east, nicknamed the E filaments (see Figure 2), are warped by the jet from NGC 3C40B. The authors decide they deserve further investigation.

Following the Field Lines

Radio waves are just a long kind of light, so they have electric fields that oscillate. The direction in which the electric fields point while they oscillate is called the polarization of the wave. As the wave travels through a magnetized plasma, its electric field (and hence polarization) rotates. This is known as Faraday rotation. The amount of rotation depends on the magnetic field strength along the line of sight, so the polarization of radio waves can be used to map out the structure of magnetic fields. The authors take great advantage of this effect. They find the E filaments have a field strength of around 1.4 x 10-10 Tesla (for comparison the Earth’s magnetic field is 3.05 x 10-5 Tesla). The field is oriented vertically at the intersection between the E filaments and 3C40B’s jet, but rotates to nearly horizontal further along their length. While bright in radio, the filaments are faint in X-rays, suggesting the fields are strong enough to block the flow of the hotter (X-ray emitting) plasma in the cluster.

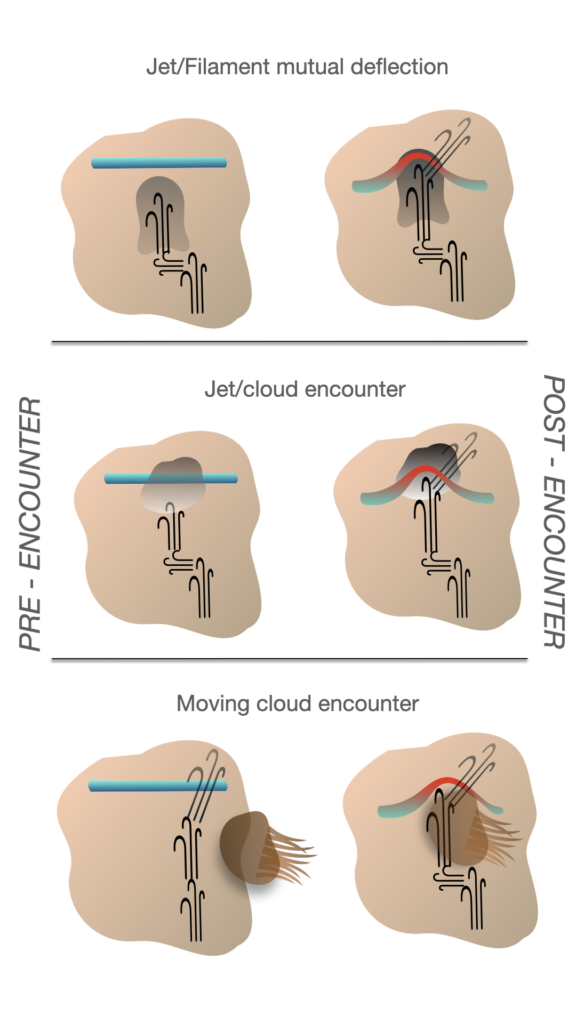

But are they strong enough to impede 3C40B’s jet? The jet bends where it intersects the E filaments, the frothing rage of a supermassive black hole seemingly blunted by flimsy filaments. However, the authors note the jet is supersonic, and in this case, the jet should be able to pass through the filaments without being deflected. Some other reason for the jet’s bending must be found. Another scenario (shown as the second panel in Figure 3) is that the magnetic filaments are embedded in a dense cloud. The jet pushes the cloud aside as it strikes, and the cloud drags the filaments along with it.

However, in real life this cloud would not be stationary. It would be orbiting the center of mass of the galaxy cluster at a speed of around 200 km/s, fast enough to cross the width of 3C40B’s jet in only 7 million years. The authors calculate in contrast, that it would take 30 million years for the jet to push its way through the cloud. This means the motion of the cloud will be important on the timescales of its interaction with the jet (third panel in Figure 3) and the jet will bend as a result of the cloud’s motion. The moving cloud scenario also handily explains why the jet bends just before it encounters the E filaments as well as at the exact point of intersection (look closely at Figure 2)–the cloud is moving eastward and shoving the jet in that direction.

In the end, if the authors’ argument is correct, then the title of this article is somewhat of a lie. The filaments and jets do not clash straight against each other; rather both are impacted by the interloping of a passing cloud. In the great Gigayears-long struggle between galaxies to determine which shall become the dominant galaxy of its cluster, this little mystery of an astronomical menage a trois may not mean much. But the drama lasts long enough that we have a chance to observe it, pause, and wonder about the clashes of forces far grander than even our own Milky Way in the night sky.

Astrobite edited by Benjamin Cassesse

Featured image credit: Figure 24 in the paper