Title: Cryolava Dome growth resulting from active eruptions on Jupiter’s moon Europa

Authors: Lynnae C. Quick, Sarah A. Fagents, Karla A. Núñez, et al.

First Author’s Institution: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Planetary Geology, Geophysics and Geochemistry Laboratory, Greenbelt, MD, USA

Status: Published in Icarus [open access]

Volcanoes, but make ‘em cold

Volcanoes are a pretty well-known phenomenon on Earth. They’re intertwined with human history in lots of ways, from causing major disasters like Pompeii, to creating the islands we live on today, and providing a lot of valuable elements that we use for farming and manufacturing. More recently, we’ve also learned that volcanoes occurred on other planets. For example, Mars is notably home to Olympus Mons (Figure 1), the largest volcano in the Solar System.

Figure 1: Image of Olympus Mons, compiled from photos by NASA’s Viking Orbiter 1. The volcano covers an area about the size of Arizona! Image Credit: NASA/JPL

On Earth, we think of volcanoes as really hot events, with lots of molten rock and superheated gas. But today’s paper takes a look at volcanoes’ colder, icier siblings, the cryovolcanoes. In the Solar System, cryovolcanoes occur on moons that are warm enough to host subsurface oceans under thick layers of ice. Instead of molten rock, they spew water onto the moon’s surface!

One of the reasons cryovolcanoes are really intriguing is their connection to ocean worlds. These worlds, often moons, are tidally heated just enough to keep liquid water beneath their surfaces, and astronomers have long thought that these oceans could be promising places to search for life. Studying how cryolava (the water equivalent of lava) spreads after an eruption can help us figure out what exactly subsurface oceans are made of and how ocean worlds could have evolved.

This work specifically focuses on cryovolcanoes on Europa, one of Jupiter’s moons. Learning more about Europa is especially exciting given the upcoming Europa Clipper mission, which will be able to study the moon up close!

Measuring cryolava domes

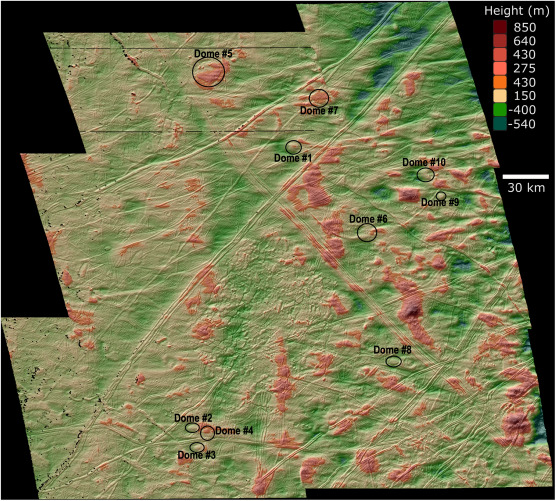

The authors select ten cryolava domes on Europa (Figure 2). These domes are the frozen remains of cryolava that previously erupted onto the surface, and they vary in size and shape. The goal of today’s paper is to use a model for how cryolava erupts and spreads to extrapolate the composition of the liquid beneath Europa’s surface.

Figure 2: Map of the cryovolcanoes studies on Europa. The colors show the height of each feature on Europa’s surface. The domes are all pretty tall (towards the red), but have a range of heights and sizes. Image Credit: Figure A-1 from today’s paper

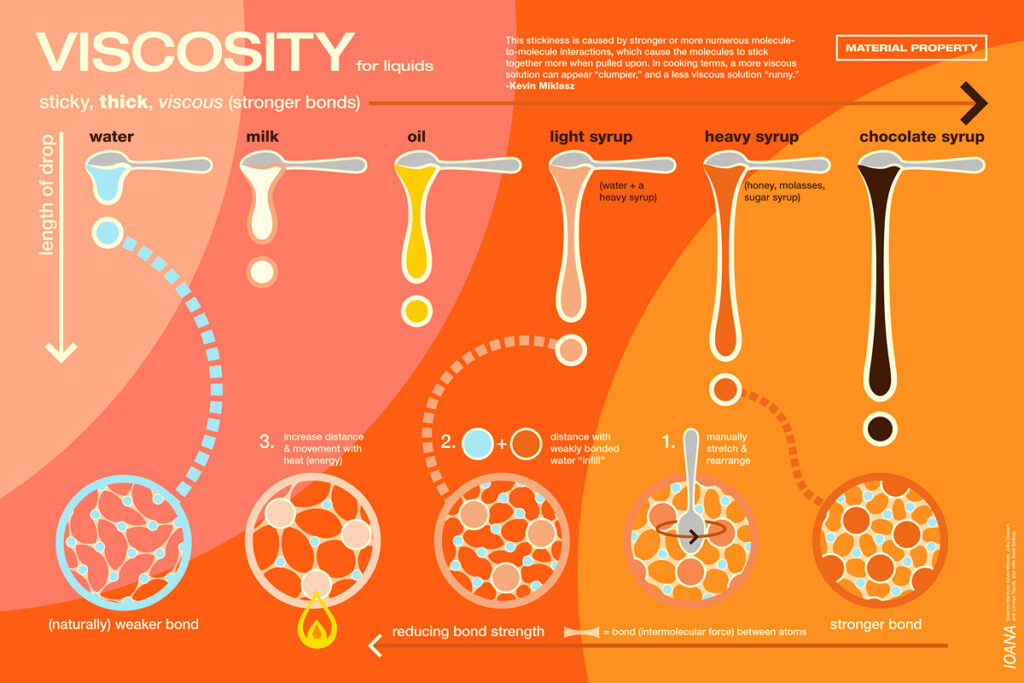

The main idea in this analysis is that different types of fluids have different viscosities. Figure 3 has a nice visual for viscosities of different fluids, but basically, high viscosity fluids are thicker, so they won’t spread out as quickly when they are expelled as cryolava. So, the authors can constrain the composition of Europa’s subsurface liquid by figuring out what viscosity is required to match the size of each observed cryolava dome. If Europa’s subsurface ocean is pure water, it would have low viscosity and create really wide but short domes, whereas taller domes might require the addition of more viscous compositions.

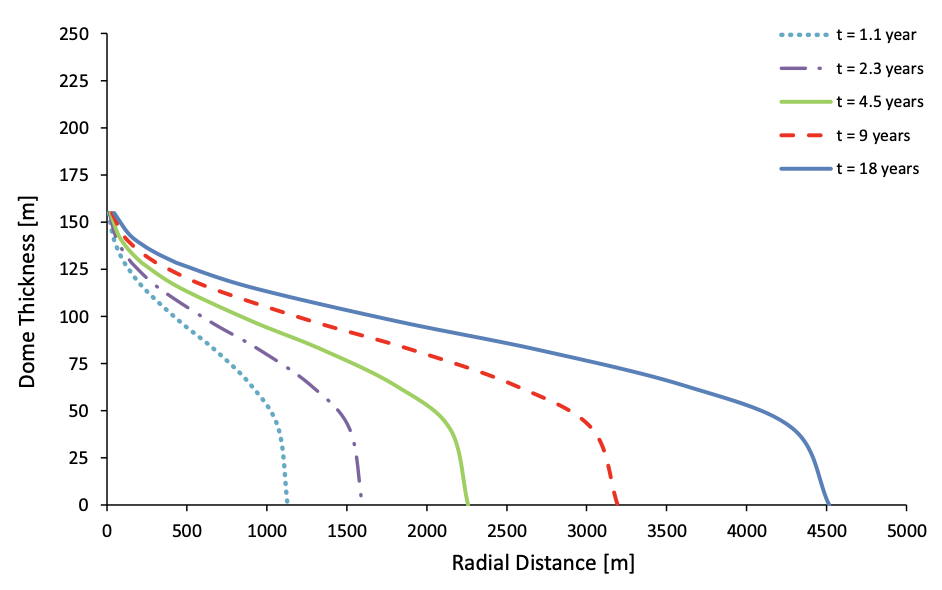

Each modeled cryovolcano gets a continuous feed of liquid from below the surface, which builds up, spreads out, and cools. The resulting pile of cryolava evolves as shown in Figure 4, widening and getting taller with time. By matching up final dome sizes, the authors can figure out if they have the right estimate for viscosity and also constrain how long it took for the eruption to take place!

Europa’s briny seas

Based on their models, the authors estimate that each dome on Europa was built over months to decades, on par with the range of lava dome timescales measured on Earth. They find that the viscosities needed to build the Europa domes require a mix of water, salt, and ice crystals (not pure water!). Interestingly, they also find that the required liquid varies between different cryovolcanoes. This could show that the cryovolcanoes all formed at slightly different points in Europa’s evolution. However, it could also be that the cryolava doesn’t all come from one big reservoir under the ice. Instead, the volcanoes might be forming out of different pockets of liquids distributed within Europa’s icy top layer, each with a slightly different composition due to how the pockets melt and freeze. These possibilities are really interesting ways to think about cryovolcanoes, and present some exciting new avenues of study for Europa and other ocean worlds!

Astrobite edited by: Catherine Manea

Featured Image Credit: Isabella Trierweiler