Paper: Linking to Data – Effect on Citation Rates in Astronomy

Authors: Edwin A. Henneken and Alberto Accomazzi

Institution: Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, MA

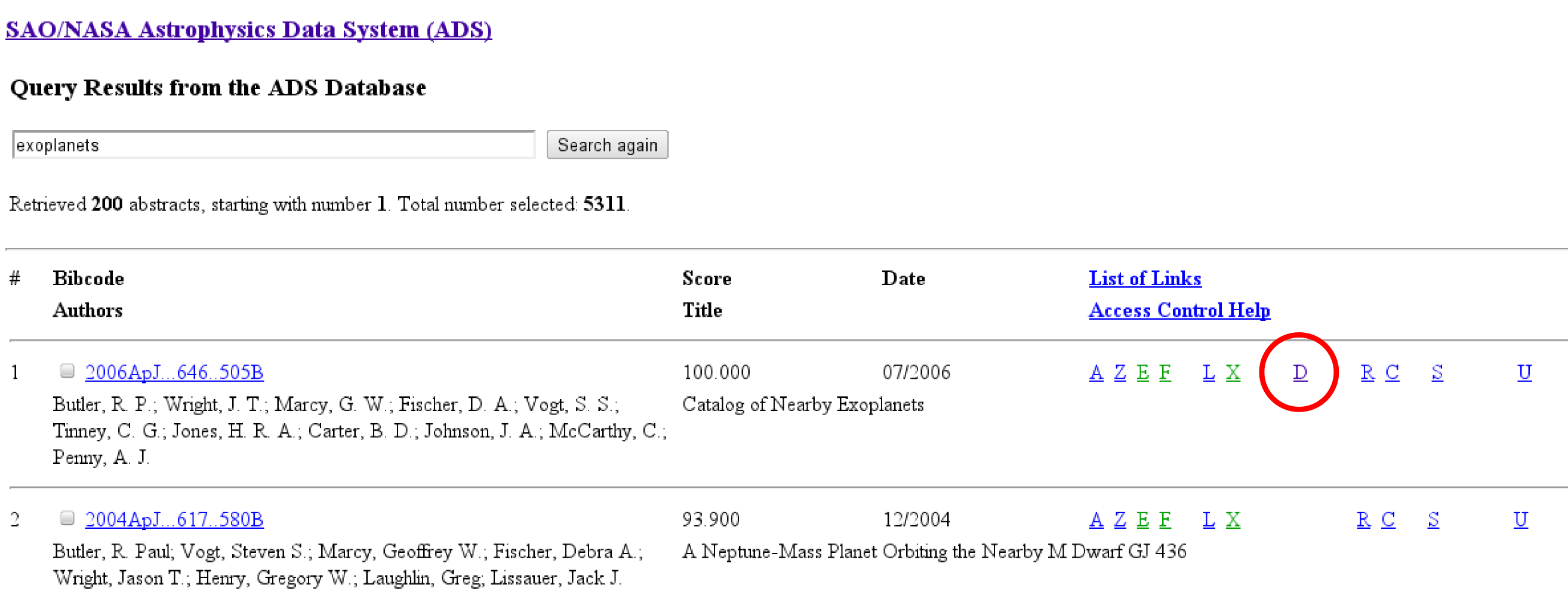

You get more in return by putting more out there, it turns out. In this modern age of astronomy, linking your paper to your dataset will result in more citations from future authors. What do I mean by “linking datasets” and “citations?” To see for yourself, spend a few minutes searching NASA’s Astrophysics Data System (more about databases here) for your favorite topic. If you’re lucky, you’ll see a few papers that have several links to the right of the row with a “D” hyperlink (see Figure 1). The “D” stands for data, and if you click on it you’ll be taken to the dataset.

The results for a search for "exoplanets" in NASA's Astrophysics Data System. If you click on the "D" hyperlink in the red circle, you'll be taken to the dataset used in the paper.

In a paper to be published as part of the proceedings from the Astronomical Data Analysis Software and Systems (ADASS) conference, Henneken and Accomazzi use the NASA ADS to investigate and quantify the effect that linking your dataset to your paper has on your citation count.

The reasons for linking to a dataset are numerous. Making your data available allows other authors to more easily interpret what you have done. Transparency in science is important–public data allows other sciences to more quickly verify (or refute) your claims. Astronomy is expensive, and archival data can sometimes be invaluable; for example, Hubble Space Telescope archival data is routinely used to search for the progenitor systems of nearby supernovae. Survey data is provided to the community so that others may tackle the questions they want to (and with their own resources). Just take a glance at how useful the Sloan Digital Sky Survey has been in providing data for papers (some astrobites on those here, here, here, …). Cross matching the sources found in surveys of different wavelengths (x-ray, UV, optical, infrared, radio) creates a very powerful, multi-wavelength view of the entire sky.

I’m sure you’ve heard the expression “5 hours in the library can save 5 months in the lab.” It’s true. Productive scientists are aware of what other scientists have done before them, that way they “stand on the shoulders of giants” so that they might see farther. Linking datasets to papers improves the usability of previously published research and is one major way to increase the overall productivity of the scientific field. Compared to other fields of science like biology or chemistry, astronomy is perhaps most amenable to archiving data. While the cells from a previous experiment in a biology lab were likely destroyed, the images from older surveys are kept on file. That means that even though in 1953 astronomers were interested in imaging object A, they also had to image object B which was in the same field of view as object A. It’s to all of our benefits that this data is made public. To see what I mean, take a look at DASCH, a survey that spans a 100 years using the digitized photographic plates from the Harvard College Observatory. New science can be done with old data.

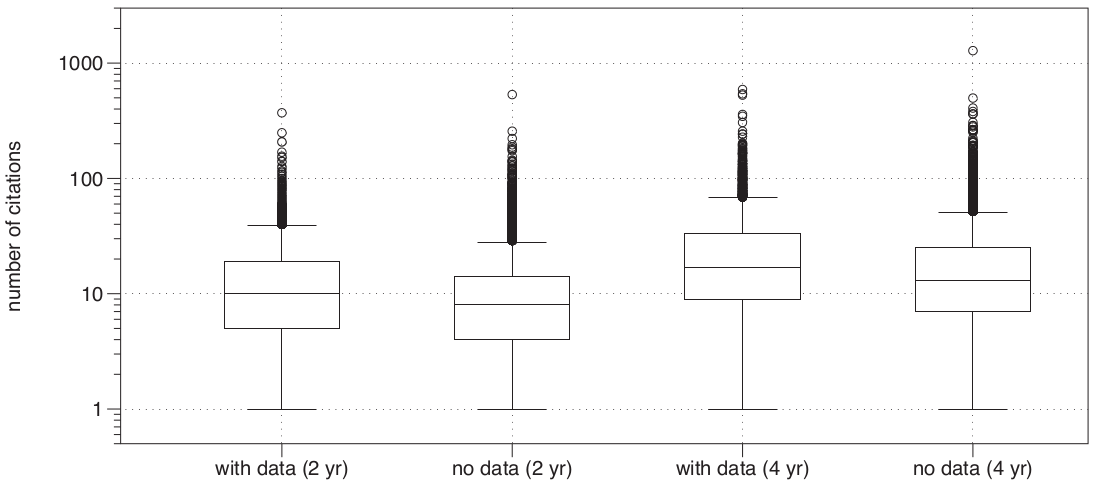

In order to investigate the effect that linking data to papers has on citation count, the authors query the ADS for citation counts of certain articles. In order to make sure that they compare similar articles, Henneken and Accomazzi design their search by first identifying the set of the 50 most common keywords that appear with dataset-linked papers. The authors then select non-dataset-linked papers by the criterion that they also include three or more of these keywords. Then, Henneken and Accomazzi analyze these two sets of “data-linked” papers and “non-data-linked” papers for citation counts and normalize the results based upon the total sample size (3814 papers for each set). Papers published with links to the datasets resulted in a significantly higher citation rate over the lifetime of the paper, whether the citation count was measured 2 years after publication date or 4 years after publication date (Figure 2).

Figure 2: A box and whisker plot from Henneken and Accomazzi. The distribution of citations to dataset-linked papers and non-dataset-linked papers measured after 2 and 4 years after publication. Notice that the dataset-linked papers had statistically significant gains in median citation count over non-dataset-linked papers. The median is the thin horizontal line inside the box. The vertical extent of the box corresponds to the interquartile range, and the vertical "whiskers" correspond to 1.5 times the interquartile range. The outlying datapoints are plotted as circles. Note the logarithmic scale for the y-axis.

In order to make sure that the two samples of papers share the same charactistics (except for data-linking), the authors examine each sample of papers for homogeneity. For example, were data-linked papers more preferentially posted to the arXiv while non-data-linked papers weren’t? Or did data-linked papers link to other databases like NED or SIMBAD more frequently? According to the authors, the data-linked paper sample and the non-data-linked paper sample were homogeneous enough to ensure that they were indeed comparing the effect of data-linking and not some other trait.

Of course, as you may have frequently heard in statistics class, correlation is not causation. Data-linked papers could simply be on average better-written papers, since an author who would spend more time to publish their dataset might have spent more time working on the text and results in the actual paper. Still, the authors hope that this statistic would encourage more authors to link to their datasets in their publications. The statistical potential for a greater citation count should provide personal incentive to link to your dataset, while the incredible utility that a public dataset provides to the field should appeal to your inner civic astronomer.