Title: Quantitative Evaluation of Gender Bias in Astronomical Publications from Citation Counts

Authors: Neven Caplar, Sandro Tacchella, Simon Birrer

First Author’s Institution: ETH Zurich

Status: An abridged version will be submitted to Nature Astronomy, [open access]

It’s no secret that there are fewer women than men who work in the sciences. Although the fraction of women has been increasing over time, most fields still have not reached parity, and various studies have shown evidence of gender bias. The authors of this bite looked at the number of citations astronomy papers published over the last 50 years have received to try and determine if there is gender bias present in citation counts. The amount of data they analyzed is impressive – 200,000 papers published in five of the biggest journals (Astronomy and Astrophysics, the Astrophysical Journal, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Science, and Nature) that publish astronomy research.

After downloading a list of all their papers of interest listed in the Astrophysical Data System (ADS), they determined the gender and seniority of the first author (in most fields of astronomy, the first author is the person who actually writes the bulk of the paper and is responsible for the majority of the research). Seniority was defined as the number of years since an author’s first publication. Since many scientists publish at least occasionally using their initials, they used a matching algorithm to match papers published under initials to those published using an author’s first name (i.e. if an author published at least one paper using their full name at some point during their career, they were able to link the rest of their papers to their record). Papers where the gender could not be determined were removed from the dataset.

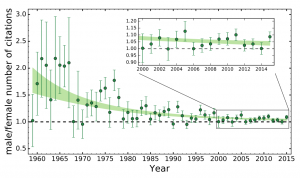

Looking at the raw data, they found that papers authored by a male received more citations than those written by a female. The ratio of male/female number of citations is larger in earlier times (although errors are large there are well due to the smaller number of papers published and the extremely low fraction of female scientists in the 1960s). Since 1990, the ratio has held roughly steady: male first-authored papers received roughly 5% more citations than papers first-authored by a woman.

Figure 1: The ratio of the average number of citations received by a male first-authored paper over a female first-authored paper. This trend is pronounced at first but has stayed roughly constant since the early 1990s. (Figure 4 from the paper)

Of course, this difference is not conclusive evidence of gender bias. The authors found some other differences between papers first-authored by men and women. For example, women tend to publish less, but their papers tend to be longer. Additionally, since women entered the field of astronomy later in time on men, as a group they tend to hold less seniority. Effects like this need to be controlled for in order to draw any conclusions.

Using a machine learning technique known as the random forest algorithm, the authors studied only the male first-author papers (for a concise definition of what a random forest is, check out this blog post). Using a few properties (seniority of the first author, number of references, number of authors, year of publication, the journal’s name, the area of the world the first author was from, and the subfield of astronomy) that are not expected to be correlated with gender, they created a way to predict the number of citations a paper would be expected to have.

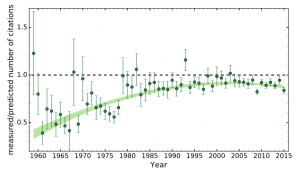

They then turned their attention to the papers first-authored by women. They found that the papers authored by women received roughly 10% less citations than their algorithm predicted.

Figure 2: Measured/predicted number of citations for papers written by females. There is a systematic effect of approximately 10%, although this is much more severe in earlier time periods (Source: Figure 6 from the paper)

While more convincing, this is still does not show with 100% certainty that this entire effect comes from gender bias. The authors note several other issues that could effect their results: the effects of self-citation, a lack of ability of their algorithm to determine the genders of non-European, non North American names, etc. The authors end the paper by encouraging the rest of the astronomical community to conduct further analyses.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks