Title: Gender gap narrows in research and innovation but inequality persists, report shows

Authors: de Kleijn, M, Jayabalasingham, B, Falk-Krzesinski, HJ, Collins, T, Kuiper-Hoyng, L, Cingolani, I, Zhang, J, Roberge, G, et al: “The Researcher Journey Through a Gender Lens: An Examination of Research Participation, Career Progression and Perceptions Across the Globe.” (March 2020) Retrieved from www.elsevier.com/gender-report

A report from She Figures published in 2018 showed a near perfect gender balance for graduate level researchers. The reasons for this likely come from simply the acknowledgement and acceptance of the existence of the gender gap over the previous years, as well as efforts into understanding the effects of gender bias, particularly in the employment processes of universities and research institutes. There have also been substantial advances in identifying what steers girls and women away from particular subjects and careers. So does this mean the end of the gender gap in the coming years across all levels of academia, not just graduate students? A study recently published by Elsevier looks into the progression of improving the gender balance over the previous years for researcher careers.

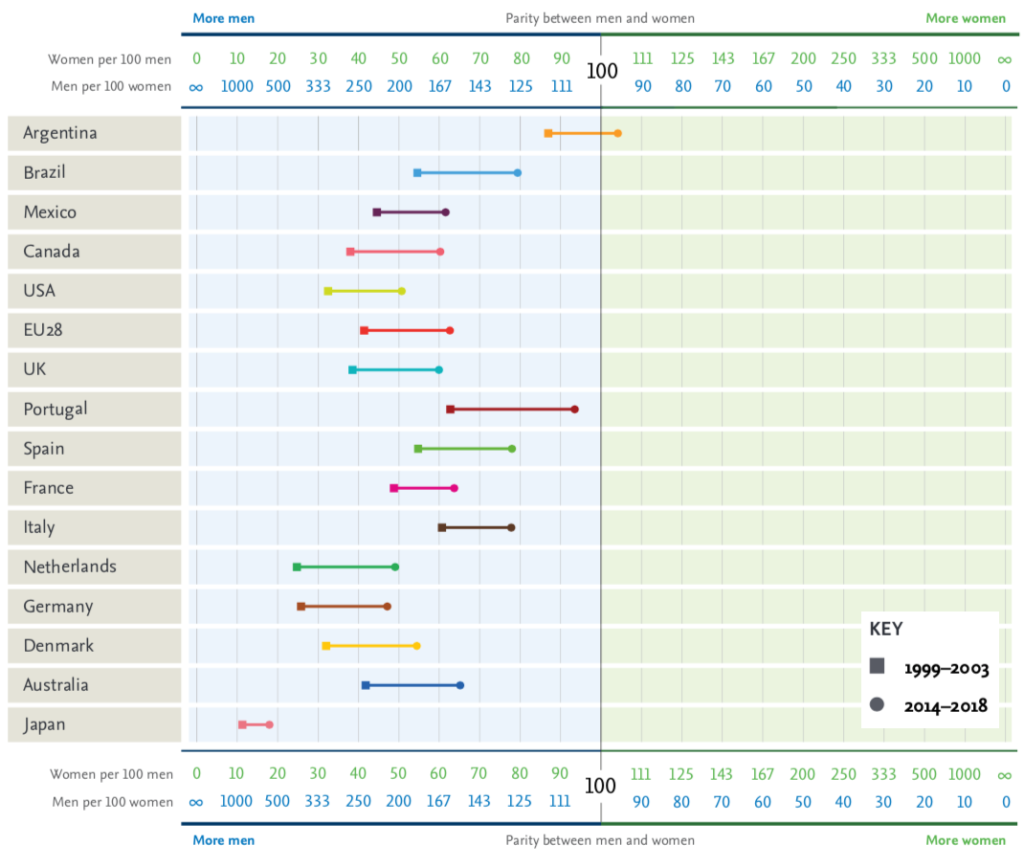

One of the main things that this study looked at was publications. (See this Astrobite for another study on this topic.) They analysed active authors (defined as spending more that 20% of their academic/work time conducting research) for 15 countries and the EU28* during the periods of 1999-2003 and 2014-2018. Authorship here constitutes any position in the author list. They found that in all countries analysed and the EU28, the ratio of women to men is closer to parity in the period 2014–2018 compared to 1999–2003. However, some countries are advancing at a much slower pace.

Portugal showed the greatest advancement in the ratio of women to men authors, from 63 women per 100 men in 1999-2003 to 94 women per 100 men in 2014-2018. Japan, however, only increased from 11 women per 100 men to 18 women per 100 men in the same periods. Argentina come closest to parity, but even has more female representation with 104 women per 100 men in the period of 2014-2018.

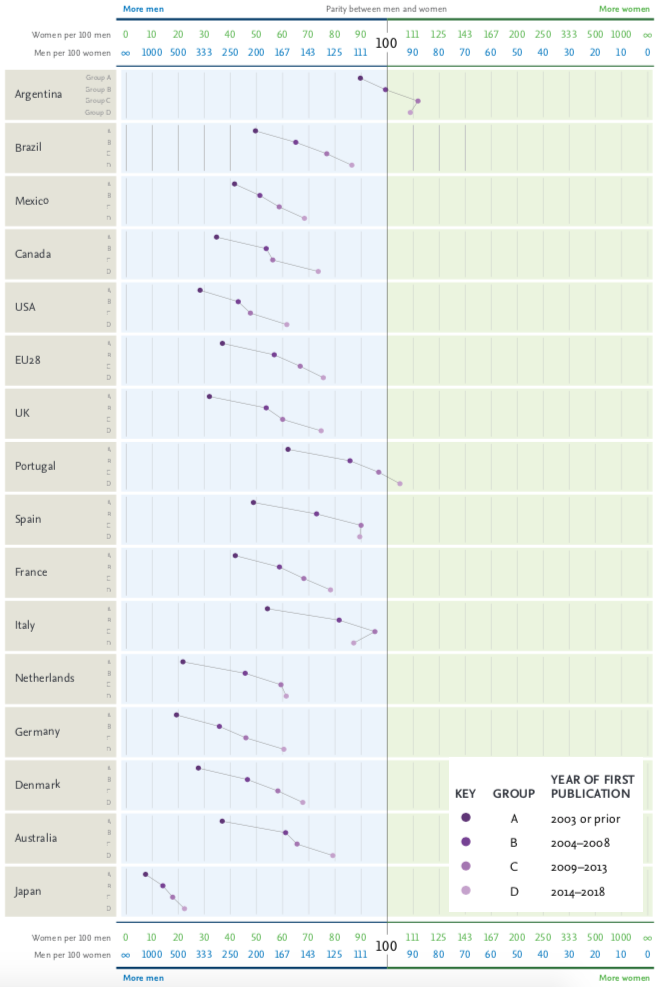

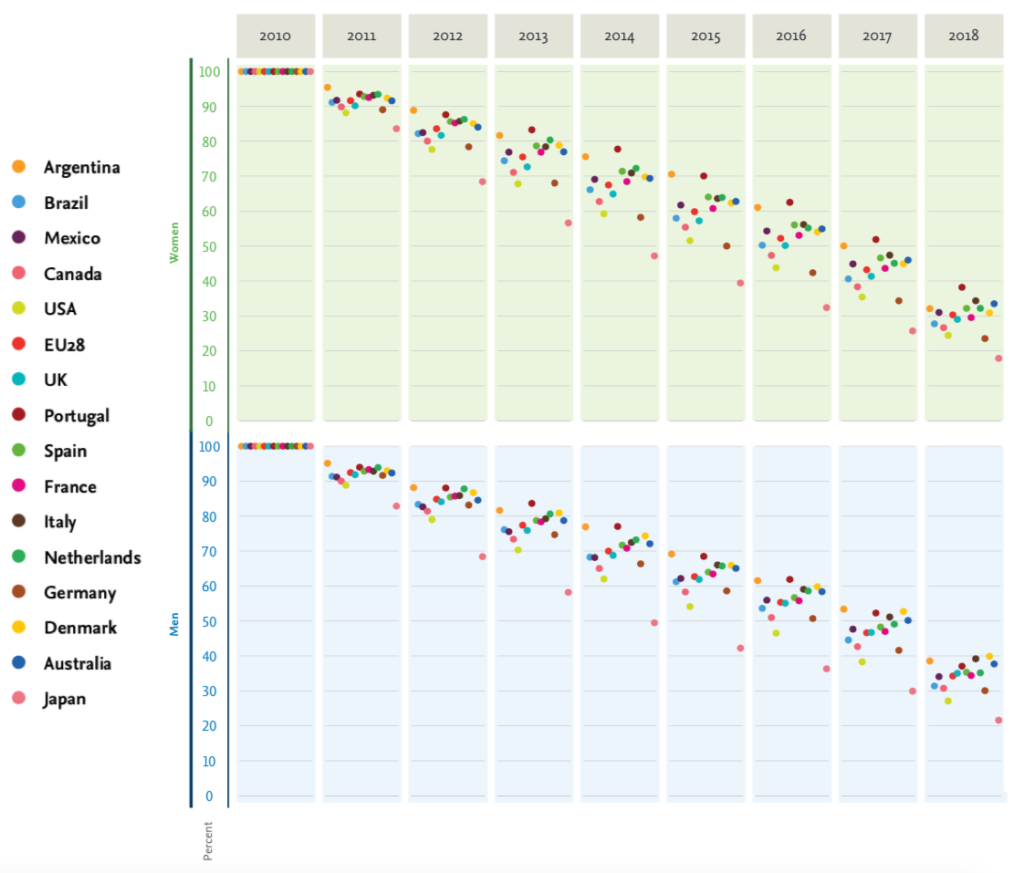

Figure 2 shows the results of grouping these active authors based on the year of the author’s first publication. The figure shows that men are more highly represented among authors with a long publication history, while women are highly presented among authors with a short publication history for nearly all countries. This is most likely due to the fact that the gender balance was worse in the past, but could also be because women are much more likely to leave academia.

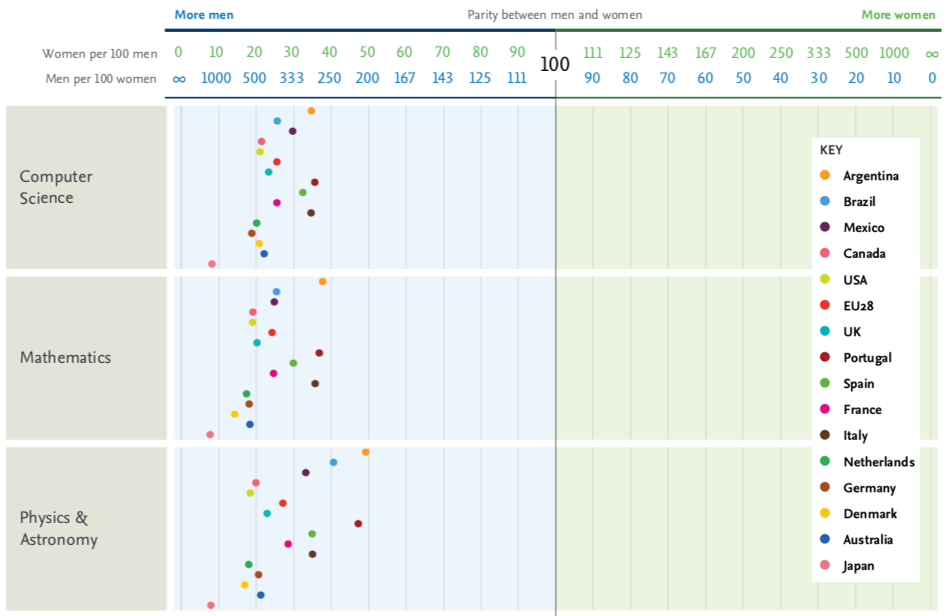

Across the countries and regions studied, the lowest ratio of women to men was observed in the physical sciences, with the median among countries ranging from 20 women per 100 men in mathematics to 51 women to 100 men in environmental science. In every subject area, among all countries surveyed, the median ratio of women to mean among active authors in 2014-2018 was higher than in 1999-2003; however, the smallest increase was in the physical sciences. In 2014-2018, the median was only 6-8 more women per 100 men than in 1999-2003 in areas such as computer science, mathematics, physics & astronomy and engineering.

The study then considers authorship position by splitting the analysis by corresponding author, first author and last author. Across all countries, they found that corresponding authors and last authors consisted of slightly more men in comparison to the total author population. Looking into this further, they found that in every country the total population of first authors mostly consisted of those who first published in 2014-2018, presumably younger researchers, whilst corresponding and last authors have been publishing for a longer time, suggesting a relationship between authorship position and seniority.

An interesting finding from this study shown in figure 4, which illustrates a steeper decline in every country in the percentage of women who continue to publish compared to the percentage of men. This is likely due to issues such as work-life balance, discussed in more detail later.

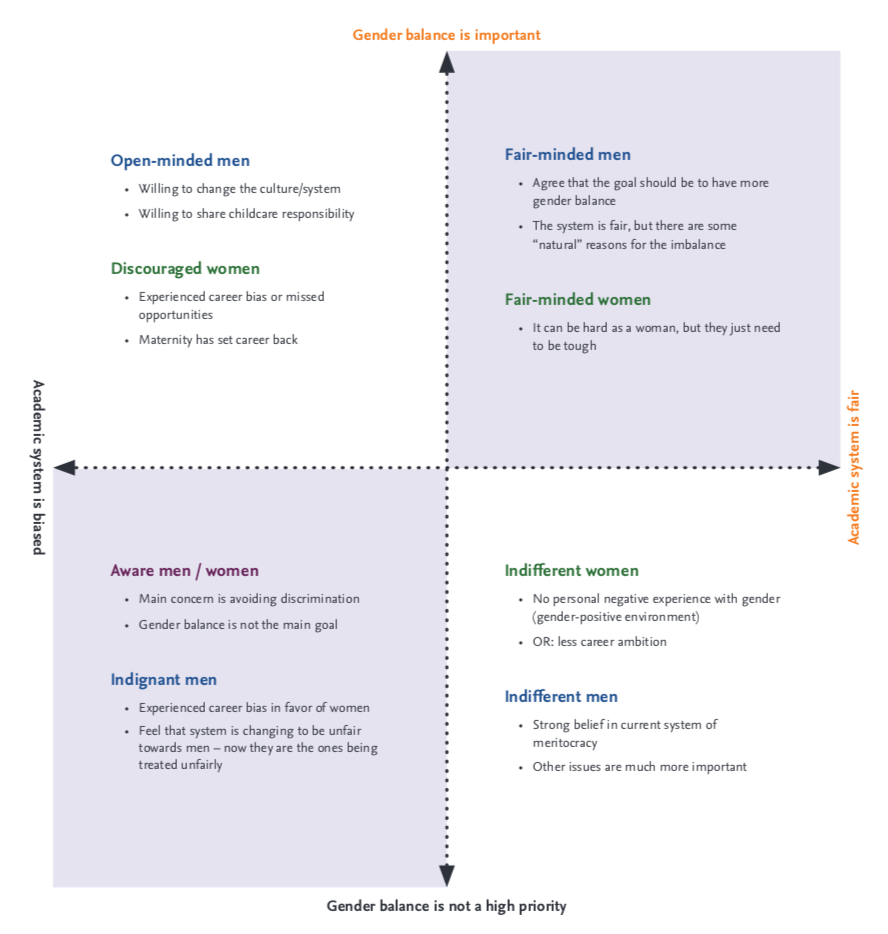

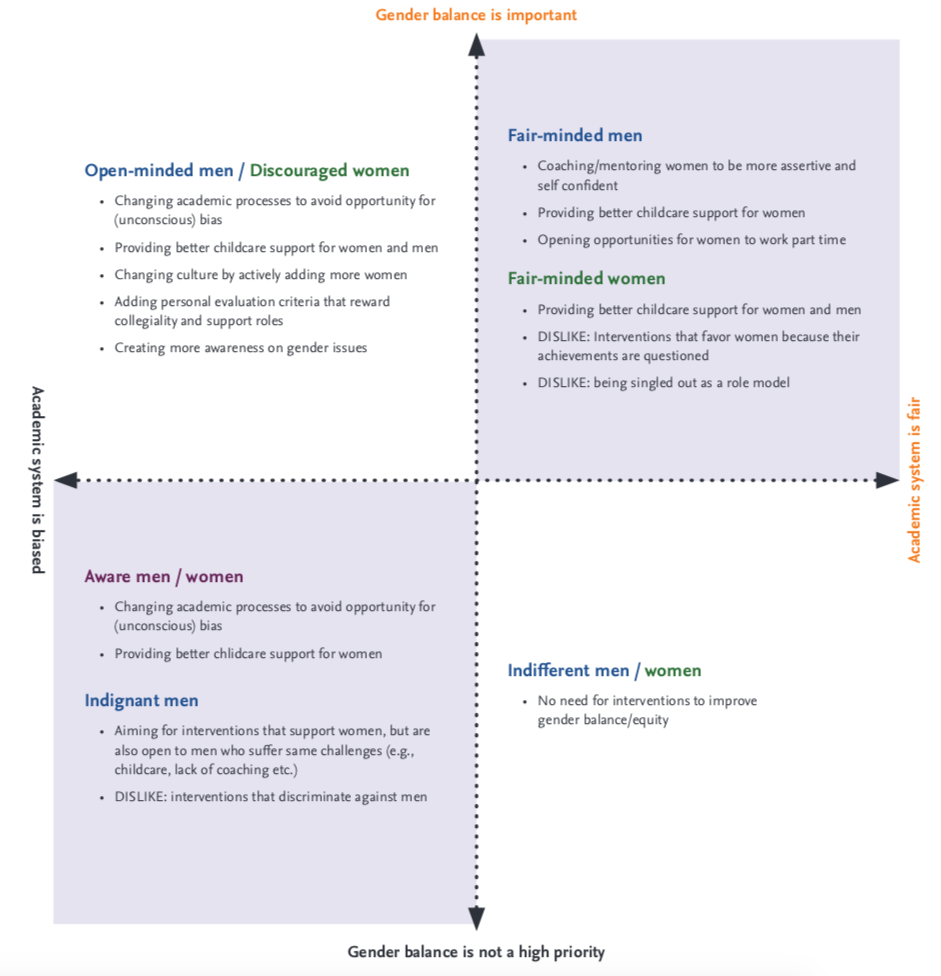

The authors also conducted a survey of around 400 researchers to try to understand the origins of the gender gap and the general attitudes towards this issue from men and women. They were able to categorise the respondents as shown in figure 5.

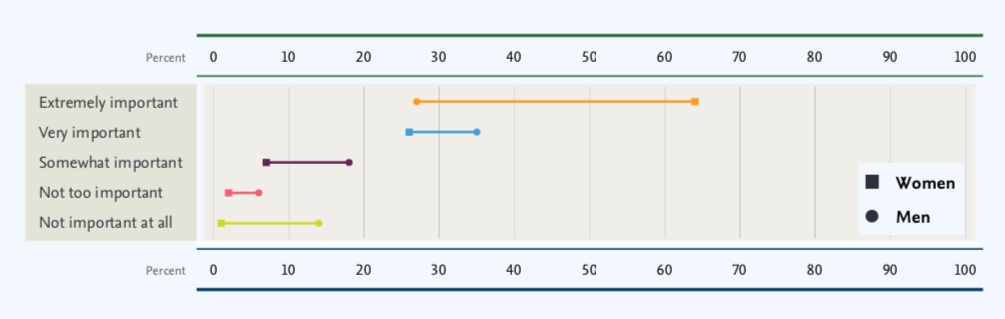

Figure 6 displays the survey respondents opinions on how important it is to have gender diversity in the research workplace. As we can see from the figure, 90% of women answered either ‘extremely important’ (64%) or ‘very important’ (26%). Of the males surveyed however, only 62% deemed this to be extremely or very important, with 14% voting that it is not important at all.

The results shown in figure 6 are also reflected in some of the opinions stated in figure 7, where we can see quotes representative of the 4 ‘groups’ outlined in figure 5. Much of the focus seems to be on the family aspect, in the sense that women take more time away from work to have children, which can be detrimental to their careers.

In order to combat these biases towards women, some suggestions are summarised in figure 8. Again, much of these suggestions are focussed on women being able to have careers in research as well as having a family. The authors of this paper suggested the following guidelines in order to achieve a better work-life balance:

- Allow flexible working hours to enable men and women to pick up children from day care or school;

- Avoid scheduling early or late meetings during times when parents need to pick up or drop off children;

- Provide childcare on campus to make it easier to pick up and drop off children and enable women to breastfeed during working hours (e.g., this is common in Germany);

- Offer the option to work part-time; though the researchers felt it would be good to have this as a personal choice, it was generally perceived that working part-time would delay a researcher’s career progress.

One of the main challenges is the very structure of academia. At the beginning of this Astrobite, we discussed a study which found near parity at graduate level, and so getting women into academia perhaps doesn’t seem to be so much of an issue anymore. However, keeping women in academia seems to be much more of a problem. A paper from 2018 looked into the number of postdoctoral researchers gaining permanent positions and found that female astronomers were leaving academia at a rate 3-4 times higher than men. They outline many reasons as to why this is happening, such as higher rates of sexual harassment as well as gender bias at the application level. However, it also supports the above survey in terms of having a family. There is a lot of pressure to continually publish, and any time away is likely to have consequences on career progression. Having children also potentially limits the ability to attend invited talks and conferences, even after parental leave has finished. This is not only limited to parenthood, as there are other factors affecting all genders such as illnesses. Some people do manage to overcome all of these barriers and succeed, but perhaps further effort can be put into alleviating this bias against people who are unable to put in the same number of hours as those without so many external responsibilities or limitations.

Academic society is becoming more aware of the issues faced in academia, and more positive measures are being put into place to broaden the opportunities of underrepresented groups. However, intrinsic facets of academia likely need to be changed to truly achieve this and potentially more drastic advances need to be made. There is very often a focus on ‘fixing’ the problem of women in academia and their representation (or lack there of) in academia, but there are many other people that these progressive measures would also help, such as single parent families and anyone with dependents such as family carers. It should also be noted that the whole way through this Astrobite, we have discussed a very binary definition of gender. This is due to the very limited definition within this study, with only the consideration of those who identify as either male or female. But, more ongoing research is also examining the challenges academia poses to those of other genders, as well as sexualities, cultures, religions, etc.

There is a lot of conversation around this topic which is great, but this paper presented today also highlights quite a significant lack of awareness of both men and women on this topic. It shows that a significant amount of work still needs to be done in spreading awareness of this issue, let alone trying to close the gap. This is not the end of the gender gap. This is the beginning of the battle, but it’s most certainly heading in the right direction.

*The EU-28 is the abbreviation of European Union (EU) which consists a group of 28 countries (Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Germany, Estonia, Ireland, Greece, Spain, France, Croatia, Italy, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Hungary, Malta, Netherlands, Austria, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia, Finland, Sweden, United Kingdom) that operates as an economic and political block.