Disclaimer: The author would first like to publicly state that Black lives and Black Trans lives matter. Secondly, the author condemns all police brutality against people of color. Lastly, the author acknowledges that the writing of this article was performed on the stolen land of indigenous people.

Where Do We Stand?

Every time I mention that I am getting my PhD in astronomy I am asked, without fail, “so, do you want to be a professor?” The question is completely warranted: I, like my other fellow graduate students, have committed to a career path that naturally ties us to academia for as long as we can remain within this system. For most of us in this field, we have been instilled with a rigid career projection that we hope to stick with as we progress further in our career. According to this idealistic plan, we complete our PhD in 5-7 years, work as a postdoctoral fellow for 2-6 years (depending on how many positions we hold) and then ultimately secure a faculty position as Assistant Professor of Astronomy. From there, we work towards being placed on the tenure track as an Associate Professor, which will then result in full tenured professorship.

But does this plan for everyone? Is our field designed to provide professorships for every PhD? If not, what are my chances of ever being a professor of astronomy? In this bite, I will explore these questions and more as I try to pin down the elusive, and ultimately terrifying rate of professorship in astronomy.

What Does the Data Say?

It is becoming abundantly clear that there is a growing discrepancy between the number of new astronomy PhDs and the amount of tenure-track positions available in astronomy departments around the world. This divide can be considered from many angles but the reality is that the problem only seems to be getting worse: the academic machine keeps churning out more and more PhDs who, after completing one or more postdocs, are faced with a relatively static pool of faculty positions. One simplistic approximation for the rate of tenure professorship in our field is to use the fact that in the US, professors across disciplines advise on average 7.4 PhD students. This means that if the number of faculty positions remains constant, only 1 in 7.4 students (~13.5%) can ultimately replace a faculty member in their field. While this thought experiment is riddled with assumptions and free variables, it is an interesting jumping off point to see how the rate of professorship could be constrained within astronomy.

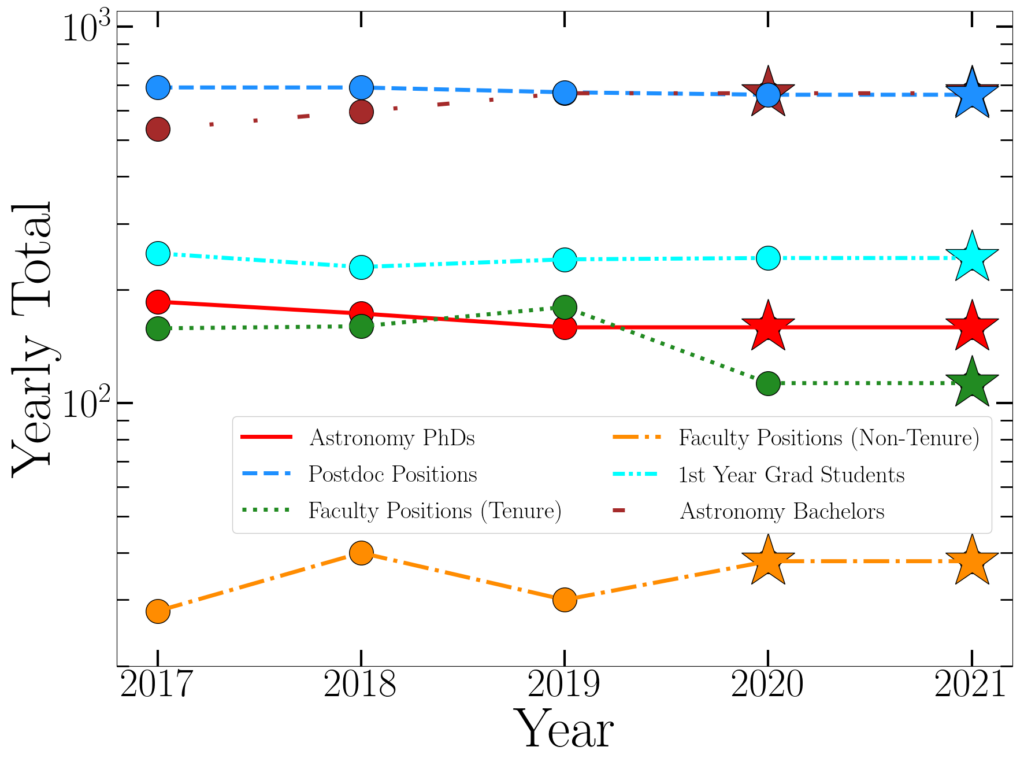

In our field, the data also appears to reflect a similarly daunting reality of becoming a tenure track professor. Shown in Figure 1 are the yearly trends of tenure track positions advertised on the AAS job register from 2017-2021 as well as other datasets such as the total number of first year grad students, confirmed PhDs, advertised postdoc positions, Bachelor’s degrees in astronomy, and non-tenure track faculty positions. As of 2019, the most recent year with complete data, the amount of tenure track faculty positions (~180) was slightly higher than the number of new US-based PhDs (~159) but lower than the 1st year class of US-based astronomy grad students (~241). This may not appear like a large discrepancy at first, especially considering that the average number of global postdoc positions available to new PhDs has remained relatively constant at ~680 positions advertised. However, there are many factors to consider.

First, ~159 of astronomy PhDs confirmed in 2019 are only for US graduate programs. When factoring in the rest of the astronomy programs around the globe, the annual total of new PhDs increases dramatically, thereby greatly surpassing the number of advertised faculty positions in 2019. Secondly, while postdoc positions are relatively plentiful in our field, they are ultimately the stepping stone between PhD and a faculty position. Consequently, hundreds of astrophysicists complete their postdocs every year and attempt to acquire one of the ~180 faculty positions advertised annually. This reveals a substantial surplus of PhDs who are seeking faculty positions, which compounds each year as more and more postdocs are denied faculty jobs only to try again in the following year with even more new applicants. In 2019, if there were ~500 postdocs looking for a tenure track faculty position, the rate of new astronomy professorships was ~36%, but likely much less.

More Data, More Barriers

It is also important to note the homogeneity of the data presented so far. The unfortunate reality is that not all faculty positions are created equal: of the ~180 positions advertised in 2019, a significant proportion (~65%) did not belong to R1 (or even R2/R3 or the non-US equivalent) universities, some positions not connected to research institutions at all. Higher ranking universities attract more esteem, more funding and, as a result, more faculty applicants, therefore decreasing the chances of obtaining these coveted positions. A tenure track position at an acclaimed research institution influences how long an astrophysicist can be funded to continue their work and further their science.

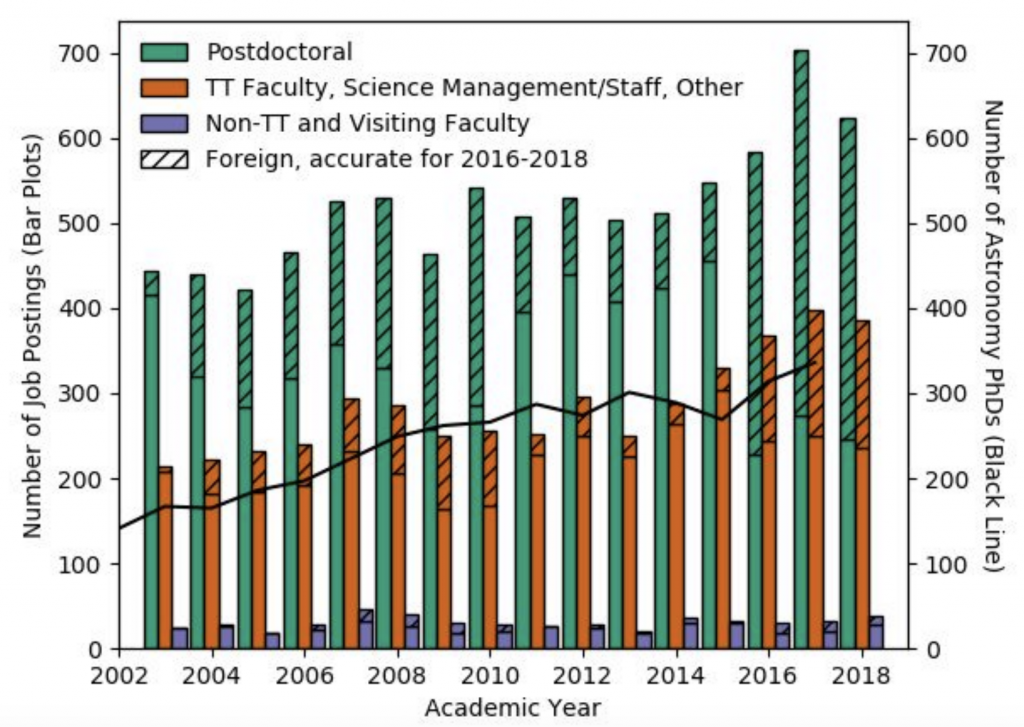

Additionally, in past years, ~1/3 of advertised faculty positions and >1/2 of postdocs were not located in the US (Figure 2), which serves as a barrier for US citizens who are not able to relocate to another country; this also applies to international PhDs looking for faculty positions outside of their own country. Lastly, the percentage of BIPOC astronomy professors is considerably lower (~21%) than cis/white/male faculty, which also reflects the rate at which these underrepresented groups obtain professorships in astronomy. Also, in 2018, women only represented 23% of astronomy faculty in the US but also comprised ~40% of confirmed PhDs that year. If the total percentage of women professors remains near this percentage, this reveals a considerably lower rate of professorship for women PhDs than their male colleagues — this rate being even lower amongst more underrepresented groups.

Where Do We Go From Here?

With each passing year, it is increasingly evident that tenure track positions in astronomy are extremely difficult to obtain. And the pressures surrounding this desire for tenure track positions is heavily derived from the stigma surrounding non-faculty positions in astronomy. Sadly, positions such as research faculty, lecturers, staff scientists, or telescope operators do not come with the same prestige, respect and financial security as tenure track professorships despite the crucial need for non-professor work in our field. There are also burgeoning career opportunities for astronomy PhDs to apply their knowledge in other fields such as data science, engineering or public policy. And so, as I revisit the question, “do you want to be a professor?” I am still filled with conflicting emotions, but I am optimistic that our field will adopt a more progressive mentality in terms of who is awarded tenure track positions and how we express value for those who are not.

Edited by: Luna Zagorac

Featured Image Credit: Aaron Geller, Northwestern University