Title: A trail of dark matter-free galaxies from a bullet dwarf collision

Authors: Pieter van Dokkum, Zili Shen, Michael A. Keim, Sebastian Trujillo-Gomez, Shany Danieli, Dhruba Dutta Chowdhury, Roberto Abraham, Charlie Conroy, J. M. Diederik Kruijssen, Daisuke Nagai, Aaron Romanowsky

First Author’s Institution: Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA

Status: Published in Nature [open access], available on arXiv

The nature of dark matter is one of the biggest mysteries in physics. All we really know about this strange type of matter is that it doesn’t experience any forces other than gravity. This makes it totally invisible, and allows it to pass through other matter, such as stars, planets and us, almost completely unnoticed. Despite this, evidence from the past several decades means that we know dark matter exists, and that there is a lot of it – about six times more than all of the visible matter in our Universe! Additionally, we know that most large astronomical structures, such as galaxies and galaxy clusters, are embedded in large, spherical haloes of dark matter.

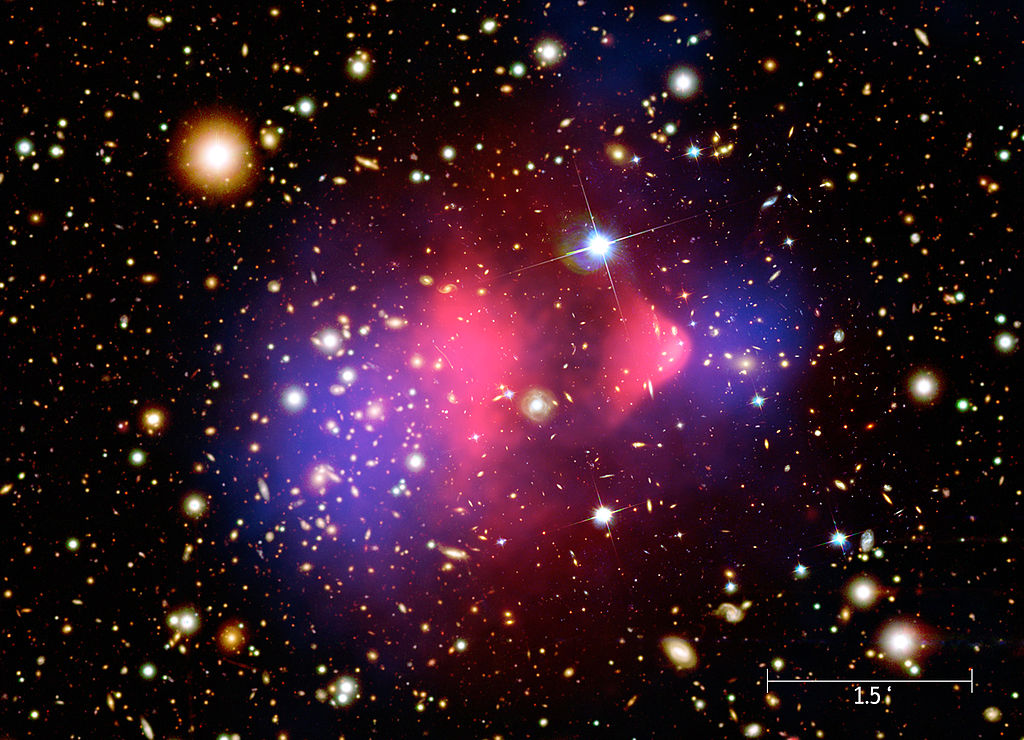

One of the most striking pieces of evidence for dark matter is the Bullet Cluster, shown in Figure 1. This image is actually the result of two galaxy clusters that have crashed into each other, and are now side-by-side. In pink, the hot, visible gas in these clusters is shown, which has been pulled towards the middle of the two clusters by drag forces. Using weak gravitational lensing to study the light from galaxies in the background of this image, we can infer the location of the matter in these clusters, which is shown by the blue areas. The fact that the distributions of hot gas and mass don’t overlap tells us that, whilst the regular matter in these clusters gets stirred up and pulled into the centre, there is some extra cluster material that is flying by unimpeded – our old friend, dark matter!

Figure 1: The Bullet Cluster, shown as three separate overlaid images. The galaxies of the two colliding clusters (as well as background galaxies) are shown in optical (visible) wavelengths. The two pink regions near the centre of the image show the X-rays emitted by the hot cluster gas, showing that these two clouds have collided and been dragged to the central region. The two blue circular regions show where the majority of the clusters’ mass is located, indicating that much of their mass is made of non-visible matter. Credit: Chandra/Magellan/NASA/STScI/ESO.

This same process can, in principle, occur on smaller scales. Today’s paper provides evidence of two dwarf galaxies having previously experienced a collision similar to the Bullet Cluster, and goes on to discuss how this could explain some of the strangest types of galaxies that we observe in our Universe.

A glancing blow

This paper looks at the NGC1052 galaxy group, and in particular, two dwarf galaxies in this group, called DF2 and DF4. These galaxies are notable because they are ultra-diffuse galaxies, which contain very few stars but have a diameter similar to other galaxies, meaning they are very faint. Many ultra-diffuse galaxies, including DF2 and DF4, also contain very little dark matter, and the reason why they differ to other galaxies in this way is still unknown.

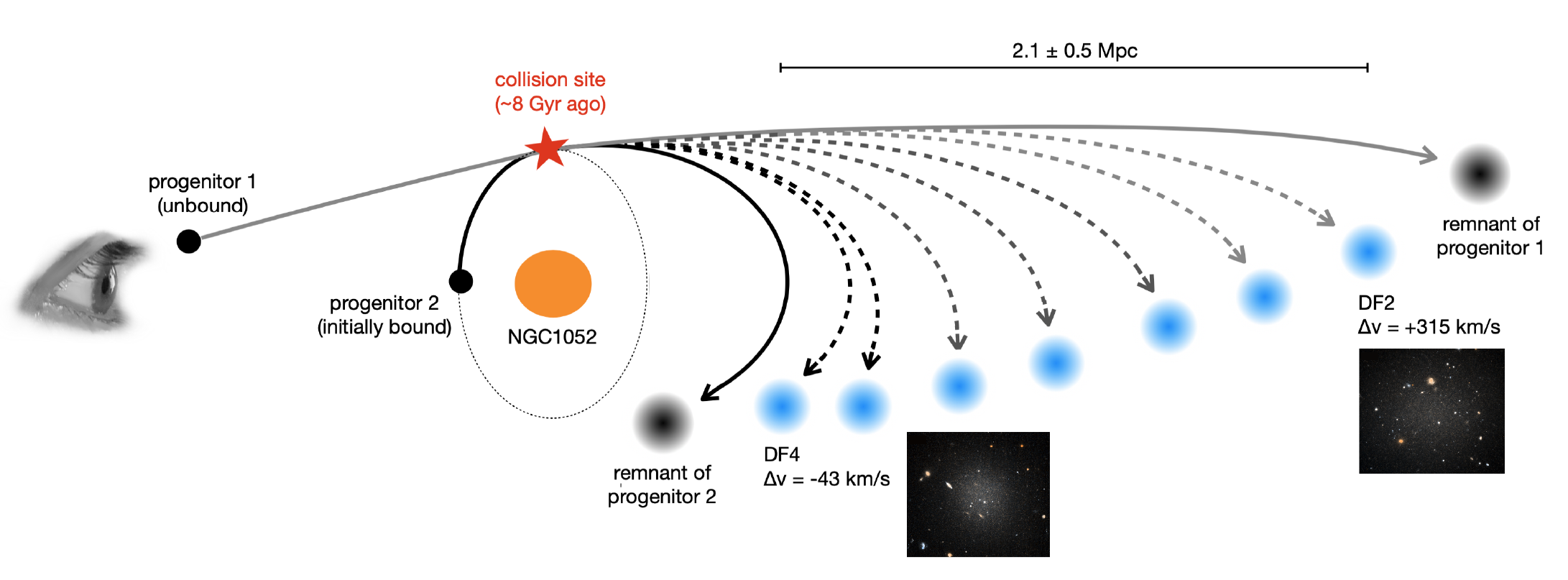

But, we may be approaching an answer! The authors suggest that a collision between two galaxies, the predecessors of DF2 and DF4, occurred about 8 billion years ago. Figure 2 shows what such a collision would have looked like, and what the result of it would be at the present day.

Figure 2: Schematic showing collision between DF2 and DF4, nearby to the galaxy NGC1052, which lies at the centre of a galaxy group. In this scenario, a galaxy (progenitor 1) collided with a member of the NGC1052 group (progenitor 2) about 8 billion years ago. This removed the stars from the dark matter haloes of progenitors 1 and 2, which then became galaxies DF2 and DF4 respectively. Parts of these galaxies were pulled away by the collision, becoming other, small galaxies between these two. Adapted from Figure 1 in today’s paper.

Such a collision could result in the positions and speeds of DF2 and DF4 that are consistent with observations: that they are separated by a distance of 2.1 Mpc (about 7 million light years) and are moving away from each other at 358 km/s. Additionally, this collision could cause the dark matter haloes and stellar components of these galaxies to separate, similarly to what occurred in the Bullet Cluster, leaving two galaxies with very little dark matter remaining: DF2 and DF4. The authors also predict that parts of these galaxies would be stripped away, leading to an arc of around 10 smaller galaxies, as well as two “dark galaxies”, made almost entirely of dark matter!

A cosmic mess

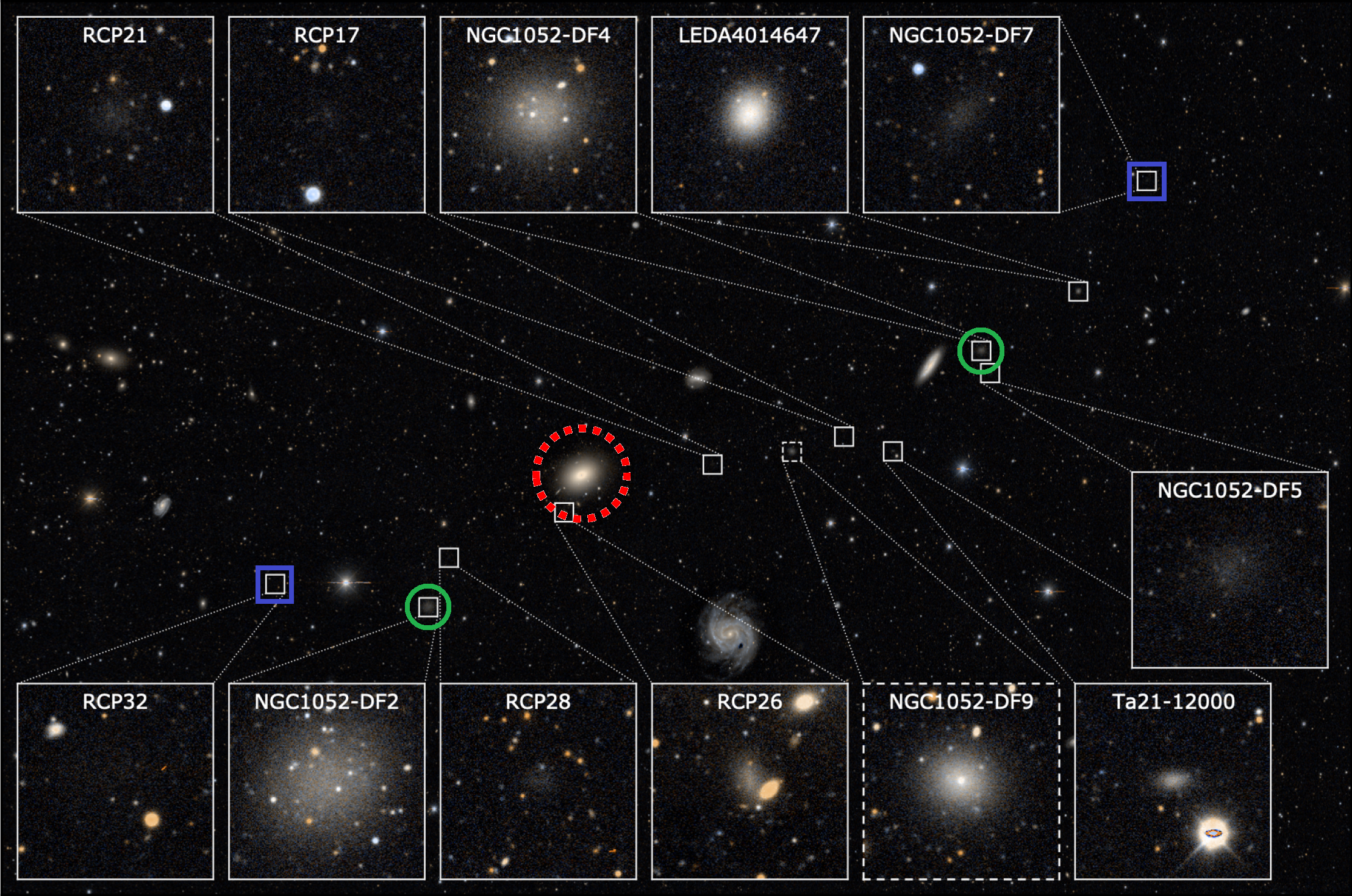

To back up their claims, the authors present observational data of DF2 and DF4, as well as the region of space between them. The image of this region is shown in Figure 3, which bears an uncanny resemblance to Figure 2! Amazingly, the observations match exactly what is predicted by a Bullet Cluster-like collision between two galaxies: a chain of small, faint galaxies located on a line between DF2 and DF4 can be seen, as well as a companion galaxy nearby to each of these two, which have both been found to be almost entirely made up of dark matter.

Figure 3: Image of NGC1052 group, and nearby galaxies. The central galaxy NGC1052 is highlighted with a dotted red circle, the ultra-diffuse galaxies DF2 and DF4 with solid green circles, and two galaxies composed almost entirely of dark matter (RCP32 and DF7) are shown by blue squares. Several other faint galaxies are marked in small white squares, along a line between DF2 and DF4, mirroring the prediction in Figure 2. Adapted from Figure 3 in today’s paper.

This work provides an origin story for the galaxies in this region of the Universe, and explains their unusual characteristics – specifically, why some have such little dark matter, and some have much more than average. Similar collisions might be able to explain other galaxies with an atypical dark matter content. Crucially though, the formation of these systems will depend on the properties of the galaxies’ dark matter haloes. Studying galaxies that have been torn apart like this could help us to constrain the properties of dark matter, and get one step closer to finally understanding this elusive portion of the Universe.

Astrobite edited by Sarah Bodansky

Featured image credit: Figure 2 from today’s paper, van Dokkum et al., 2022