Title: The large scale limit of the observed galaxy power spectrum

Authors: Matteo Foglieni, Mattia Pantiri, Enea Di Dio, Emanuele Castorina

First Author’s Institutions: Leibniz Supercomputing Centre, University of Milan

Status: Accepted to Physical Review Letters [closed access]

If you’ve been paying attention to the world of cosmology, you might have heard quite a bit of press about tensions in the so-called ΛCDM model, which describes our current best assumptions about the structure, content, and history of the Universe. Part of the beauty of this model is its simplicity–it covers the entirety of cosmic time in just six parameters–but that simplicity may prove to be its downfall, as cosmologists continue to search for effects that may complicate the picture. Today’s authors discuss one such complication, and how it could affect our observations of galaxies billions of light years away.

The devil in the details

The CMB, or Cosmic Microwave Background, is made up of light that began propagating just 380,000 years after the Big Bang, at a redshift of around 1100. It depicts a Universe that is remarkably homogeneous and isotropic; in other words, the CMB photons are the same temperature no matter what direction you look in or what part of spacetime you observe, to within one part in 100,000. What tiny variations in temperature do exist are assumed under ΛCDM to be completely random (more specifically, to follow a Gaussian distribution), and form the seeds of the galaxies and galaxy clusters that we live in today.

Although the CMB fluctuations are random to a good approximation, many theories predict that the underlying distribution is not, in fact, fully Gaussian. If we can detect such primordial non-Gaussianities (PNG) in our observations, it will be yet another source of data about the tensions in the ΛCDM model, and will allow us to distinguish between our many different ideas of the physics of the extremely early Universe.

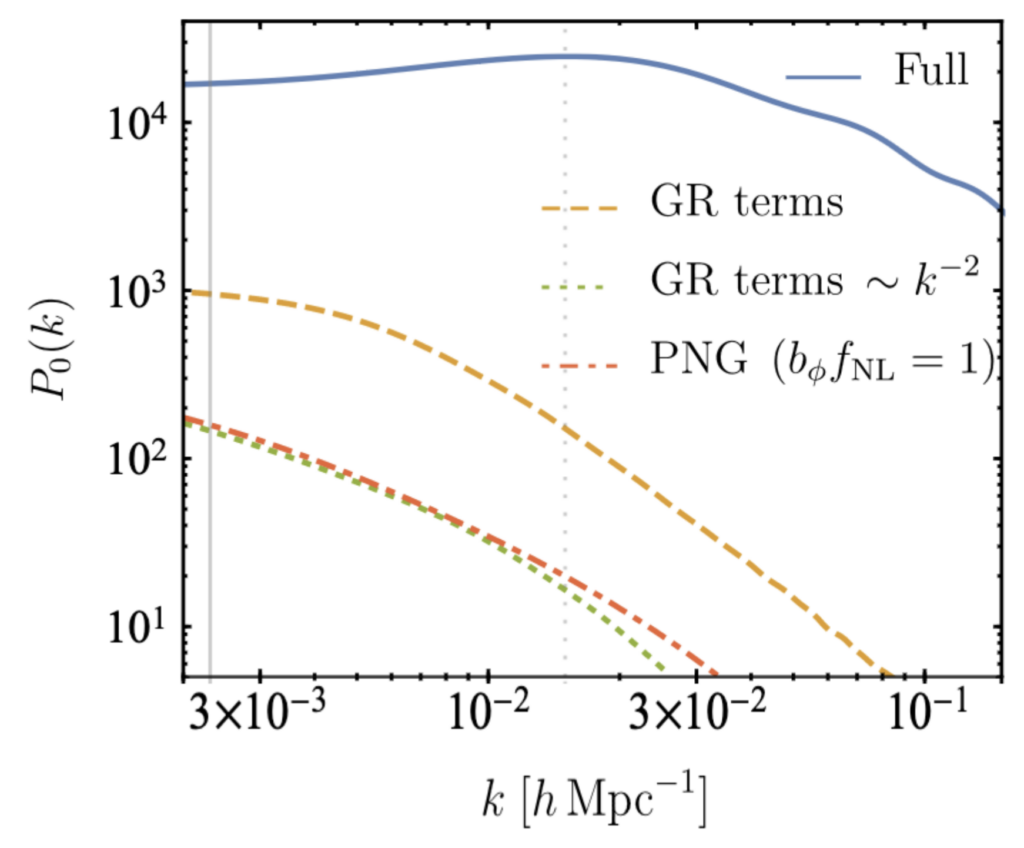

One problem with searching for primordial non-Gaussianities is that some more recent, non-primordial effects can mimic them in our data. As light propagates through an expanding and changing Universe towards our telescopes, it can encounter relativistic projection effects that cause its wavelength to change. This could potentially distort our observations of the galaxy distribution on large scales in ways that are similar to the distortions caused by PNG, even though the effect actually originates much more recently. Astronomers have been hotly debating the extent of the potential distortion for years; could projection effects really mimic PNG, and how well?

The big picture

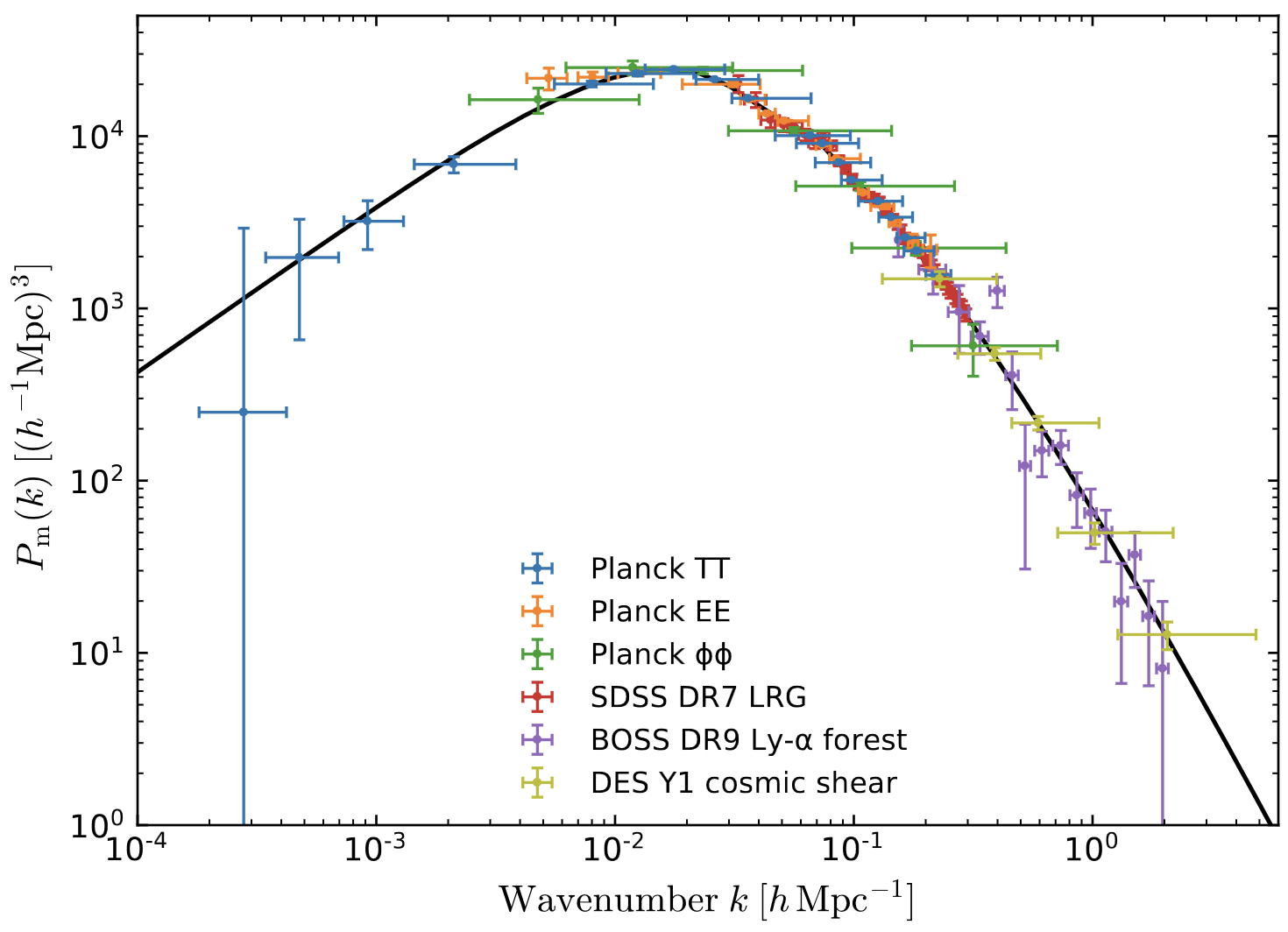

To get to the bottom of this confusion, today’s authors consider the observed matter power spectrum, which describes the difference between the density of a given patch of spacetime and the mean density of the Universe as a function of the volume being considered. The shape of this curve, shown in Figure 1, is well known over a wide variety of scales, but here we are specifically interested in especially large fluctuations (or small wavenumbers, on the left side of Figure 1). The matter distribution at these scales is sensitive to the initial conditions at the very beginning of the Universe, and is where we need to look if we want to find PNG.

To see whether projection effects and primordial non-Gaussianities could contribute to the matter power spectrum in similar ways, the authors of today’s paper compare their predicted shapes and strengths directly. Although the two are physically distinct and do not behave in exactly the same way, they find that some relativistic effects could indeed mimic a PNG, with a similar amplitude and proportionality to the scale k.

While our data about the large-scale end of the matter power spectrum is limited, and the resolution we would need in order to observe primordial non-Gaussianities is much higher than that of what is currently available, future missions will be able to reach this level of precision. Today’s authors have shown the necessity of including as many physical phenomena as possible in our analyses. In doing so, not only do we better understand the data, but we also gain the ability to make and report future groundbreaking discoveries. Who knows what we might find?

Astrobite edited by Junellie Gonzalez-Quiles

Featured image credit: Andrew Pontzen/Fabio Governato