- Title: Predictions of the Atmospheric Composition of GJ 1132b

- Authors: L. Schaefer, R. D. Wordsworth, Z. Berta-Thompson, and D. Sasselov

- First Author’s Institution: Harvard-Smithsonian Centre for Astrophysics

- Paper Status: Accepted at ApJ.

Pictured is Mustafar, a world covered in red-hot magma (or lava, if you prefer). Mustafar is from Star Wars (and, I’m afraid, from the prequels), but there are several non-fictional planets that might be real-universe “lava worlds”, due to their intense heat. The Earth, and the other rocky planets of the Solar system, are believed to have formed with temperatures high enough for their surfaces to be molten. In today’s article, we take a look at how this “ocean of magma” might affect the way that a planet’s atmosphere evolves.

Mustafar, a Star Wars lava world. (Image from Wookiepedia.)

The team were studying the evolution of planets with water-dominated atmospheres, in particular the rate of loss of the water’s constituent hydrogen and oxygen parts (the two are not necessarily lost at the same rate). This loss happens by several mechanisms. Of most interest to us today is a so-called “thermal escape mechanism”, in which a particle with enough energy can travel fast enough to break free of the planet’s gravity and escape into space. In this way hydrogen will be lost faster than oxygen, because its lower mass means it needs less energy to escape. The energy in this case comes from radiation from the planet’s host star, particularly in the ultraviolet part of the electromagnetic spectrum (UV).

Indeed, much of the previous work in this area has found that hydrogen disappears from the planet’s atmosphere while some amount of oxygen is left behind, forming O2. This could be bad news for hopes that O2 might be used as a sign of life on other worlds. However, it also might not be the whole picture. The same models predict that Venus, in our own solar system, should have this residual atmosphere of O2, but we see no sign of it.

Where does the magma come in?

One possible solution to the problem might involve interactions between the planet’s atmosphere and its surface, particularly when the surface is molten as water can dissolve in molten rock. Today’s authors attempted to include these interactions with the planet’s surface in their models of the atmosphere. The surface in their models begins as an ocean of magma, then slowly cools to solid rock. The team then attempted to model a water atmosphere, allowing H and O to both escape into space and dissolve into the surface.

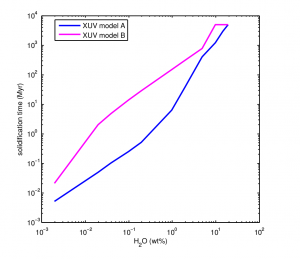

Figure 1: The solidification time of the magma ocean depended on the amount of water in the atmosphere — the more water there was, the slower the ocean solidified, because of the greenhouse effect. The ocean also lasted longer in models with less radiation from the star (magenta) than in models with more radiation (blue). For models in which more than 10% of the planet’s mass was water, (the top of the lines here), the magma lasted for the entire length of the calculations, a total of 5 billion years! (Picture credit: Figure 5 from today’s paper.)

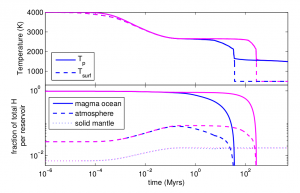

The team found that the length of time it takes the ocean to solidify depends strongly on the amount of water they give the atmosphere at the start of their models — water is a greenhouse gas, and so the more water there is in the planet’s atmosphere the longer it takes the planet to cool. They found that the atmospheric composition at the end of their models depended on the atmospheric composition at the start, on the amount of UV light hitting the planet, and on the composition of the magma ocean.

Figure 2, above: the temperature of the planet’s mantle and surface evolving over time, for models with more stellar radiation (blue) and less (magenta). Below: The fraction of the total amount of water contained in the magma ocean, the atmosphere and the solid mantle over time. The magma ocean’s fraction drops off as the ocean solidifies, and almost all of the atmospheric fraction is lost to space; however, the fraction trapped in the solid mantle increases as the ocean solidifies, and remains after the rest is lost. (Picture credit: Figure 4 from today’s paper.)

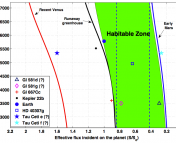

The team applied their models to GJ 1132b, a recently discovered exoplanet about the size of the Earth that orbits 65x closer to its star than we do. GJ 1132b is a planet whose atmosphere should not be too difficult to study, so today’s authors hope to use future measurements of its atmospheric composition to test the predictions of their models. Their predictions for GJ 1132b depend on their starting conditions: if they set models going with a large initial amount of water — more than 5% of the planet’s mass — they can produce atmospheres with a large amount of oxygen, steam or both (with oxygen atmospheres more likely if the planet receives a large amount of UVs). Due to the greenhouse effect, a steam atmosphere implies that the planets surface is probably still molten. However, most of their starting conditions — any model with less than 5% water — result in an atmosphere with only a thin shell of O2 and no steam.

Observations of GJ 1132b should be able to measure its atmospheric composition and test the team’s predictions. Until then, their model is applicable, not only to plenty of other exoplanets, but also to Venus, where they expect the magma ocean to have cooled much faster due to Venus’ greater distance from the sun.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks