English

This guest post was written by Sabina Sagynbayeva, a graduate student at Stony Brook University. She graduated from Nazarbayev University in Kazakhstan in 2020. She is passionate about planets and stars. Now she works on the kinematics of planet formation developing hydrodynamical numerical simulations.

Title: Orbital Clustering in the Distant Solar System

Authors: Michael E. Brown and Konstantin Batygin

First Author’s Institution: Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology

Paper Status: Submitted to The Astronomical Journal [open access]

In 1894, Percival Lowell, the founder of the Lowell Observatory, was dreaming about finding the ninth planet in our Solar System, which he called Planet X. Unfortunately, he died without finding it, but the search for Planet X continued. Eventually, Clyde Tombaugh found Pluto, which is now a member of trans-Neptunian objects in the Kuiper belt family.

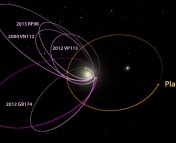

Kuiper belt objects (KBOs) follow their own rules and are randomly oriented in space. But Konstantin Batygin and Michael Brown noticed something strange happening: some distant KBOs are aligned in one direction, and also their orbits are tilted in the same direction. To account for this preferred direction, 4 years ago they hypothesized another world in our Solar System – Planet 9. Though it gives an elegant explanation to the perturbations of the trans-Neptunian objects with exceptionally long and elongated orbits, it has never been observed. Batygin and Brown are working hard with the Subaru Telescope to find it; until then, it remains known as the Planet 9 Hypothesis. However, not everyone believes to the given hypothesis, mainly citing the effect of observational biases. In today’s paper authors address those biases and discuss the statistical significance of the clustering.

Are the clusters real?

The Planet 9 Hypothesis relies on clustering of distant KBOs that also have to be aligned in one direction with their orbits tilted. The important question that should therefore be answered is: are the proposed clusters real? After all, as of July 2018 only 14 of such objects were found – not 14,000. The authors decided to attempt to answer this question by looking at the longitude of perihelion bias (or bias in the alignment) and at the orbital pole bias (or bias in the tilt of the orbits) separately, as well as the both of them combined.

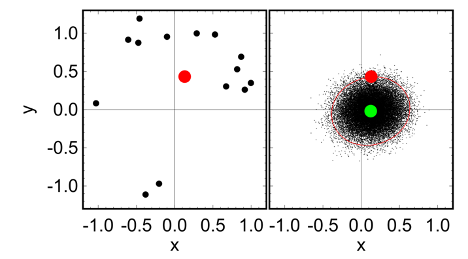

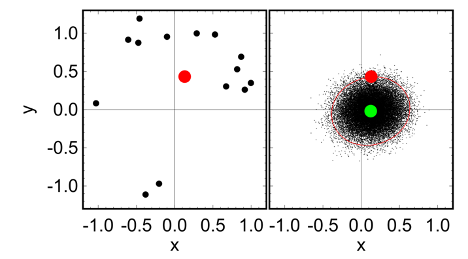

Considering the alignment bias first, they looked at the 14 known KBOs with perihelion beyond Neptune and semimajor axis beyond 230 AU (distant KBOs). They attempted to answer the question statistically, excluding Planet 9 from this study. The authors ran a simulation with random 100,000 observations of uniformly distributed alignments for each of 14 KBOs, and represented the average as black dots in Fig. 1. They noticed that only 4% of them were as strongly clustered as the real data (represented as the red dot on the right panel of Fig. 1), and the other 96% fall near zero (enclosed within the red ellipse). Here, we have 1-in-25 chance that this happened by random. This is quite a low probability of the KBOs being clustered randomly, which strengthens the idea that the clustering is not just an observational bias.

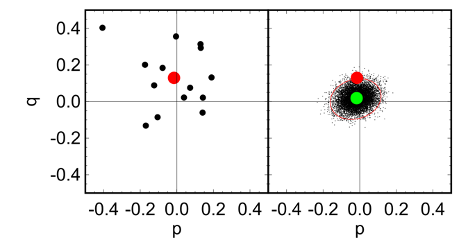

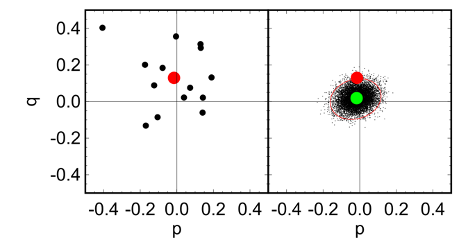

By making an analysis analogous to the abovementioned one, they examined the bias in the tilts. The results showed that there were only 3.5% of the orbits were tilted (Fig. 2).

Now let’s see what happens if we combine both the longitudes of perihelion and the position of the pole biases. Because of the dependency of the two cases, the authors had to calculate the probability combining the two cases. The resulting probability was even smaller than one would even expect. There is only 0.2% chance of the strong clustering of the longitudinal perihelions and the orbital pole positions! This result emphasizes the importance of the statistical significance of the clustering.

Figure 1. Left panel: black dots are 14 known KBOs and the position of the longitude of perihelion in the (x,y)-space (vectors that the authors used as clustering of the longitude of perihelion). The red dot is their average position (0.13, 0.43). The distance away from the origin of this average is a measure of the strength of the clustering. Right panel: the result of a simulation of 100,000 iterations of randomly selected positions of longitude of perihelion of the 14 KBOs. Each of the black dots is the average of those iterations. The red dot shows the extreme case. Fig. 1 in the paper.

Figure 2. Left panel: black dots are 14 known KBOs and the direction of the north pole of the orbit in the (p,q)-space (vectors that the authors used as clustering of the pole position). The red dot is their average position (-0.02, 0.13). Right panel: the result of a simulation of 100,000 iterations of randomly selected positions of the north pole of the orbit of the 14 KBOs. Each of the black dots is the average of those iterations. The red dot shows the extreme case. Fig. 2 in the paper.

Can other discoveries hurt the Planet 9 hypothesis?

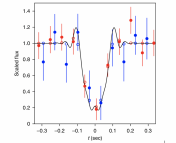

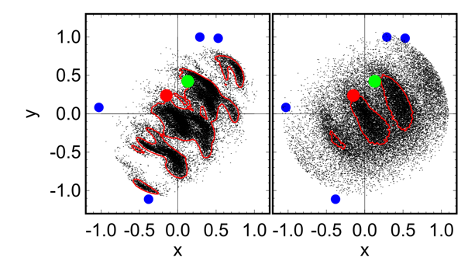

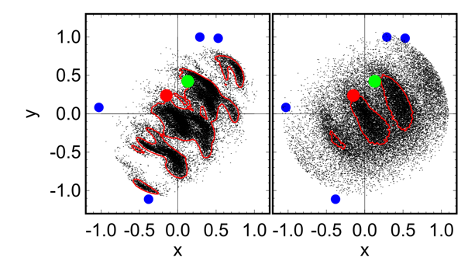

A quite recent result from the OSSOS survey, which looks for the worlds beyond Neptune, claims that there is no clustering. The problem was that the 4 distant KBOs, that were observed by OSSOS, were not clustered. The authors of today’s paper decided to examine those observations. They applied the same technique as discussed above but on the 4 KBOs discovered by OSSOS (Fig. 3). The result can be seen in the red contours, which enclose 85% of the points, in the left panel of Fig. 3. Therefore, there is only a 15% chance that the simulated OSSOS objects would be more clustered than the real OSSOS objects. For the further examination, the authors used an alternate method to compute biases using the reported bias function. Repeating the analysis using this alternate method, the strong clustering could be detected at the 65% confidence level. Using these numbers, the authors conclude that even if the clustering was as strong as expected, the OSSOS survey was statistically incapable of confidently detecting the clustering due to the limited region of the survey and small number of detected objects. They claim that OSSOS might find the objects that do not cluster, and this is acceptable within the framework of the Planet 9 hypothesis.

Figure 3. Left panel: blue dots are 4 KBOs discovered by OSSOS in the authors’ (x, y)-space. The red dot is the average of the OSSOS discoveries, the green dot is the set of 14 KBOs discussed above. The black dots show 100,000 iterations of randomly selected averages of the longitudes of perihelion. Right panel: the alternate method of bias computing is used. Blue dots are 4 KBOs discovered by OSSOS in the (x, y)-space. Red dot is the average of the OSSOS discoveries, the green dot is the set of 14 KBOs discussed above. The black dots show 100,000 iterations of randomly selected averages of the longitudes of perihelion. Fig. 4 in the paper.

Lowell’s dream came true?

None of the above analyses give a direct answer as to whether the Planet 9 is out there or not. However, something might have caused the clusters of the distant KBOs, and Planet 9 is an elegant solution to them. So, even though Pluto is not a planet anymore, Lowell’s dream might still come true through Mike Brown and Konstantin Batygin and their Planet 9.

Astrobite edited by: Luna Zagorac

Featured image credit: Caltech/R. Hurt (IPAC)

Russian

Этот гостевой пост был написан Сабиной Сагынбаевой, магистранткой Университета Стоуни-Брук. Она окончила Назарбаев Университет в Казахстане в 2020 году. Она увлечена планетами и звёздами. Сейчас она работает над кинематикой образования планет, разрабатывая вычислительные гидродинамическое модели.

Название: Орбитальная Кластеризация в Далёкой Солнечной Системе

Авторы: Майкл Браун и Константин Батыгин

Учреждение первого автора: Отделение Геологических и Планетарных Наук, Калифорнийский Технологический Институт

Статус статьи: отправлено в The Astronomical Journal [открытый доступ]

В 1894 году Персиваль Лоуэлл, основатель Лоуэлловской обсерватории, мечтал найти девятую планету в нашей Солнечной системе. Назвал он её Планетой Х [читается Планета «Икс»]. К сожалению, он так и не успел найти её, но после его смерти поиск Планеты X продолжился. В итоге, Клайд Томбо нашёл Плутон, который теперь является членом транснептуновых объектов в семействе пояса Койпера.

Объекты пояса Койпера (ОПК) следуют своим собственным правилам, ориентируясь в пространстве совершенно случайным образом. Однако, Константин Батыгин и Майкл Браун заметили кое-что странное: некоторые далёкие ОПК выровнены в одном направлении, в то же время имея наклонённые в одном направлении орбиты. Чтобы объяснить это предпочтительное направление, 4 года назад они выдвинули гипотезу о другом мире в нашей Солнечной системе – Планете 9. Хотя она даёт элегантное объяснение возмущениям транснептуновых объектов с исключительно длинными и вытянутыми орбитами, она никогда не была найдена. Батыгин и Браун усиленно работают с телескопом Subaru, чтобы найти её; до тех пор она остаётся известной как гипотеза о Планете 9. Однако, не все верят данной гипотезе, в основном ссылаясь на эффект ошибок наблюдения. В сегодняшней статье авторы обращаются к этим ошибкам и обсуждают статистическую значимость кластеризации.

Являются ли кластеры настоящими?

Гипотеза Планеты 9 основывается на кластеризации удалённых ОПК, у которых совпадает аргумент перигелия и их орбиты ориентированы в пространстве приблизительно одинаково. Поэтому необходимо ответить на важный вопрос: реальны ли предполагаемые кластеры? Ведь к июлю 2018 года таких объектов было найдено всего 14, а не 14 тысяч. Авторы решили попытаться ответить на этот вопрос, рассматривая ошибку аргумента перигелия и ошибку в полюсе эклиптики по отдельности, а также оба случая вместе.

Учитывая ошибку аргумента перигелия, они рассмотрели 14 известных ОПК с перигелием за Нептуном и большой полуосью больше 230 а.е. (удалённые ОПК). Они попытались ответить на вопрос статистически, исключив Планету 9 из этого исследования. Авторы провели моделирование со случайными 100 000 наблюдениями равномерно распределённых аргументов перигелия для каждого из 14 ОПК и представили среднее значение чёрными точками на рис. 1. Они заметили, что только 4% из них были столь же сильно кластеризованы, как и реальные данные (представленные как красная точка на правой панели рис. 1), а остальные 96% попадают около нуля (заключены в красный эллипс). Шанс 1 к 25, что это произошло случайно. Это довольно низкая вероятность случайной кластеризации ОПК, что укрепляет идею о том, что кластеризация – это не просто ошибка наблюдений.

Проведя анализ, аналогичный вышеупомянутому, они исследовали ошибку в наклонах. Результаты показали, что только 3,5% орбит были наклонены (рис. 2).

Теперь посмотрим, что произойдет, если мы объединим ошибки в аргументах перигелия и полюсах эклиптики. Так как оба этих случая зависимы друг от друга, авторам пришлось вычислить вероятность объединяя два случая. В результате вероятность оказалась даже меньше, чем можно было бы ожидать. Вероятность сильного скопления аргументов перигелиев и полюсов эклиптики составляет всего 0,2%! Этот результат подчёркивает важность статистической значимости кластеризации.

Рис. 1. Левая панель: чёрные точки — это 14 известных ОПК и положение аргумента перигелия в (x, y) -пространстве (векторы, которые авторы использовали для кластеризации аргумента перигелия). Красная точка – их среднее положение (0,13, 0,43). Расстояние от этого среднего значения является мерой силы кластеризации. Правая панель: результат моделирования 100 000 итераций случайно выбранных положений аргумента перигелия 14-ти ОПК. Каждая из чёрных точек — это среднее значение этих итераций. Красная точка показывает особый случай. Рис. 1 в статье.

Рис. 2. Левая панель: чёрные точки — это 14-ти известных ОПК и направление северного полюса эклиптики в (p, q) -пространстве (векторы, которые авторы использовали для кластеризации положения полюса). Красная точка – их среднее положение (-0,02, 0,13). Правая панель: результат моделирования 100 000 итераций случайно выбранных положений северного полюса орбиты 14 КБО. Каждая из чёрных точек — это среднее значение этих итераций. Красная точка показывает особый случай. Рис. 2 в статье.

Могут ли другие наблюдения противоречить гипотезе о Планете 9?

Совсем недавний результат исследования OSSOS, который ищет объекты за Нептуном, утверждает, что кластеризации нет. Проблема заключалась в том, что 4 удалённых ОПК, которые наблюдались OSSOS, не были кластеризованы. Авторы сегодняшней статьи решили изучить эти наблюдения. Они применили ту же технику, что описана выше, но на 4-х ОПК, обнаруженных OSSOS (рис. 3). Результат можно увидеть в красных контурах, которые охватывают 85% точек, на левой панели рис. 3. Следовательно, только 15% вероятность того, что смоделированные объекты OSSOS будут более кластеризованы, чем реальные объекты OSSOS. Для дальнейшего изучения авторы использовали альтернативный метод для вычисления систематических ошибок. Повторяя анализ с использованием этого альтернативного метода, можно было обнаружить сильную кластеризацию с уровнем достоверности в 65%. Используя эти числа, авторы приходят к выводу, что даже если кластеризация была такой сильной, как ожидалось, OSSOS был статистически неспособен с уверенностью обнаружить кластеризацию из-за ограниченной области обзора и небольшого количества обнаруженных объектов. Они утверждают, что OSSOS может найти объекты, которые не кластеризуются, и это приемлемо в рамках гипотезы Планеты 9.

Рис. 3. Левая панель: синие точки — это 4 ОПК, обнаруженные OSSOS в пространстве (x, y). Красная точка — это среднее значение открытий OSSOS, зелёная точка — это набор из 14 ОПК, описанных выше. Чёрные точки показывают 100 000 итераций случайно выбранных средних значений аргумента перигелия. Правая панель: используется альтернативный метод вычисления ошибки. Синие точки — это 4 ОПК, обнаруженные OSSOS в (x, y)-пространстве. Красная точка — это среднее значение открытий OSSOS, зелёная точка — это набор из 14 ОПК, описанных выше. Чёрные точки показывают 100 000 итераций случайно выбранных средних значений аргумента перигелия. Рис. 4 в статье.

Мечта Лоуэлла сбылась?

Ни один из приведенных выше анализов не даёт прямого ответа на вопрос, существует ли Планета 9 или нет. Однако, что-то могло вызвать скопления далеких ОПК, и Планета 9 – изящное решение для них. Итак, хотя Плутон больше не является планетой, мечта Лоуэлла всё еще может осуществиться благодаря Майку Брауну и Константину Батыгину и их Планете 9.