Title: 2MASS J13243553+6358281 is an Early T-Type Planetary-Mass Object in the AB Doradus Moving Group

Authors: Jonathan Gagné, Katelyn N. Allers, Christopher A. Theissen, Jacqueline K. Faherty, Daniella C. Bardalez Gagliuffi, Étienne Artigau

First Author’s Institution: Carnegie Institute of Washington

Status: Published in Astrophysical Journal Letters, open access on arXiv

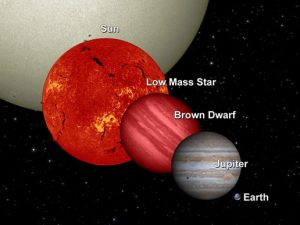

Figure 1. A comparison of the sizes of Sun-like and low-mass stars to brown dwarfs, gas giants, and terrestrial planets. Though brown dwarfs have only slightly larger radii than Jupiter, they contain more than ten times the mass. Image courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCB.

Stars dutifully fuse hydrogen into helium throughout their main-sequence lifetimes, while planets quietly fuse nothing at all. In between these two extremes—large and hot enough to fuse deuterium but too small and cool to process its lighter cousin, hydrogen—lie brown dwarfs (see Figure 1). Like giant planets, they have cloudy atmospheres and sport polar aurorae. Like stars, they are powered by nuclear fusion, but unlike stars, they cool as they age, which could have interesting implications for the development of life on planets orbiting around them.

Astronomers have discovered over a thousand brown dwarfs, ranging in spectral type from the barely-sub-stellar late M-dwarfs to the ultra-cool Y-dwarfs, but questions about their formation, interior goings-on, and early lives remain. Of particular interest is the lower end of the mass range: Where do we draw the line between brown dwarfs and planets? And where do the transitions between brown dwarf spectral types lie?

A Curious Brown Dwarf in AB Doradus

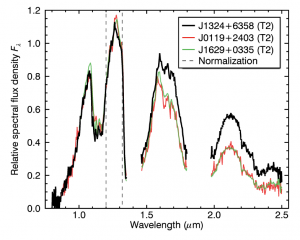

Figure 2. The spectral energy distribution of 2M1324+6358 (black line) compared to two other T2-dwarfs. 2M1324+6358 is much brighter at long wavelengths than either of the other T2-dwarfs, which could mean that it’s an unresolved binary. Figure 1 from the paper.

In this paper, the authors investigate an object that has defied past classification attempts: 2MASS J13243553+6358281, or 2M1324+6358 for short. Other than being the top baby name for 2018, this unwieldy name tells us where to find the object in the sky and that it was cataloged by the Two Micron All-Sky Survey. Previous observations of this object (see Figure 2) indicated that it might be a single, very young brown dwarf or an unresolved binary system composed of two brown dwarf flavors: one L-dwarf and one T-dwarf.

In order to learn more about 2M1324+6358, the authors first determine whether or not it belongs to AB Doradus, a young (~150 million years old), nearby (~20 parsecs away) moving group. A moving group is a collection of stars, traveling together through the Galaxy, that formed at the same time from the same cloud of gas and dust. It’s much easier to figure out the age of a group of stars than an individual star, and since all stars in a moving group formed at the same time, figuring out if an object belongs to a moving group tells us its approximate age. Combining luminosity and color measurements with distance and age gives modelers the information they need to determine the brown dwarf’s radius, temperature, and surface gravity—critical info for exploring the muddy waters between small stars and giant planets.

First, the authors use parallax to determine the distance to 2M1324+6358. The parallax measurements hint that 2M1324+6358 belongs to the moving group because it’s at the same distance from the Earth. It’s not enough to just be at the right distance, though; stars are constantly in motion, and it’s common for a star to escape its natal cluster and mosey through neighboring clusters. However, a star that’s just passing through will tend to have a different velocity from stars that belong to the cluster, so if 2M1324+6358’s distance and velocity both match AB Doradus’, it’s very likely to belong. The authors pass the object’s velocity and location to a Bayesian statistical framework and find a cluster membership probability of 98%—bingo!

2M1324+6358: One Brown Dwarf or Two?

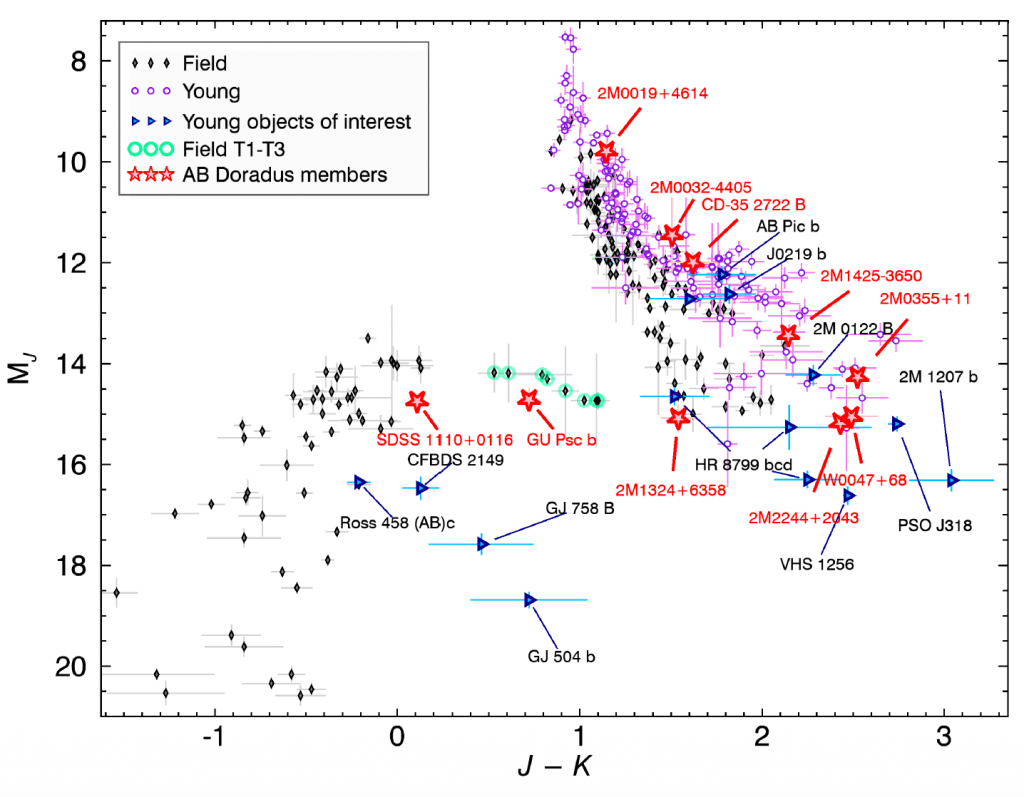

Figure 3 shows that 2M1324+6358 is fainter than other objects of similar spectral type, which means it’s unlikely to be a binary system. As a member of the AB Doradus moving group, it must also be young—just about 150 million years old. Young brown dwarfs are thought to be highly variable, due to both stellar activity and clouds drifting through their atmospheres, which could explain the unusual spectral features that led past studies to conclude it was a binary.

Figure 3. Color-magnitude diagram showing 2M1324+6358 (J-K ~ 1.6) in relation to other likely AB Doradus moving group members and field stars. 2M1324+6358 is slightly fainter in J-band than other T-dwarfs. Figure 4 from the paper.

With the potential binary reduced to a single object, it’s also possible to estimate its radius and mass: just 20% larger than Jupiter and 11-12 times as massive, making 2M1324+6358 one of the nearest known planetary-mass brown dwarfs! While there is still much we don’t know about young brown dwarfs, studying nearby objects like 2M1324+6358 can help us understand what fills the gap between small stars and large planets.

Featured Image: Artist’s conception of a brown dwarf streaked with clouds. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Please note that a brown dwarf is not powered by nuclear fusion. Even though they (at least the most massive ones) do fuse deuterium early in their lives, the very definition of a brown dwarf implies that it never reaches the point of sustained hydrogen fusion as stars do -they never reach the main sequence. Hence, the statement that “like stars, they are powered by nuclear fusion” is incorrect. This is namely why they cool as they age, because they lack a sustained source of energy to keep their temperature constant.