Title: A HOT SATURN ORBITING AN OSCILLATING LATE SUBGIANT DISCOVERED BY TESS

Authors: Daniel Huber, William J Chaplin et al

First Author’s Institution: Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawai‘i, USA

Status: Submitted to AAS journals, closed access

NASA’s space mission TESS is currently hunting for new exoplanets in the southern hemisphere sky. But while its primary aim is to find 50 small planets (with radii less than 4 Earth radii) with measurable mass, there is a lot of other interesting science to do. Today’s paper presents the discovery of a new exoplanet that is quite precisely characterised thanks to the complementary technique of asteroseismology used on the same data.

Meet TESS

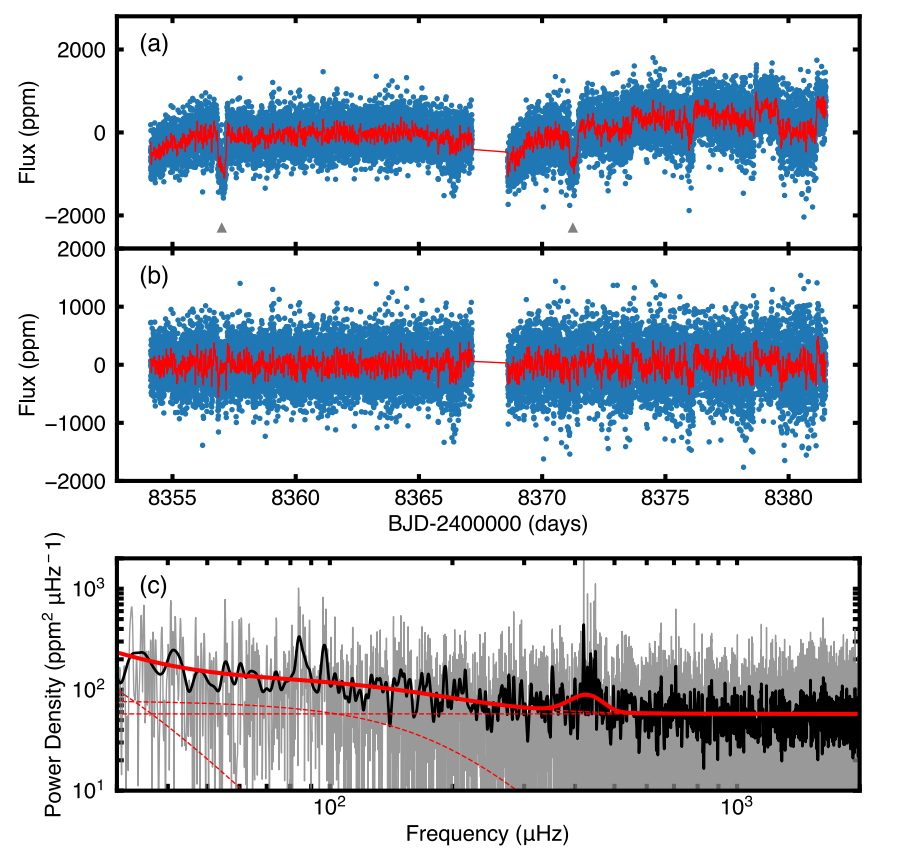

TESS will survey stars over the entire sky, studying 26 strips for 27 days each. Data for selected bright stars is downloaded to give data points every 2 minutes, then processed through a pipeline to produce lightcurves. Another pipeline detects transit-like signals in these lightcurves. One of the planet candidates it identified was TOI-197.01 (see Figure 1a).

Is it an exoplanet?

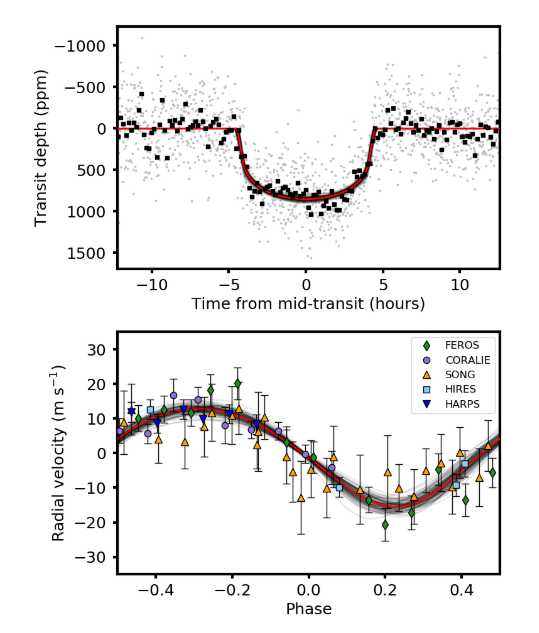

The authors used high resolution imaging by the NIRC2 camera on the Keck telescope to rule out companion stars that could produce a similar lightcurve. An intense spectral monitoring campaign of 111 spectra from 5 different instruments in a seven week period let them search for periodic Doppler shifts in the stellar spectrum caused by the mass of another object tugging on the star. The mass they calculated from these radial velocities (seen in Figure 3) confirmed TOI-197.01 as an exoplanet.

Stellar pulsations

Photometry from space is not only useful for finding exoplanets: Kepler could detect the periodic changes in stellar brightness caused by stellar pulsations or ‘star quakes’ (listen to them here). Asteroseismology, the study of these pulsations, allows astronomers to investigate the inner structure of bright stars and calculate their key properties, including radius and mean density, very precisely. Astronomers expected they could also study stellar pulsations using TESS data.

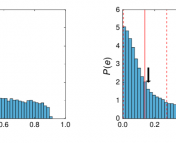

After removing the transit signal from the TESS light curves (giving Figure 1b), the light curve is fourier transformed from time (days) into frequency (microHz), giving the power spectrum seen in Figure 1c. Modelling the stellar pulsations along with the stellar granulation and white noise (see Figure 1c), the authors then ‘smoothed’ the power spectrum to identify the tallest peak, i.e. the frequency of maximum power at 430 microHz and its height, or power.

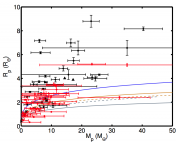

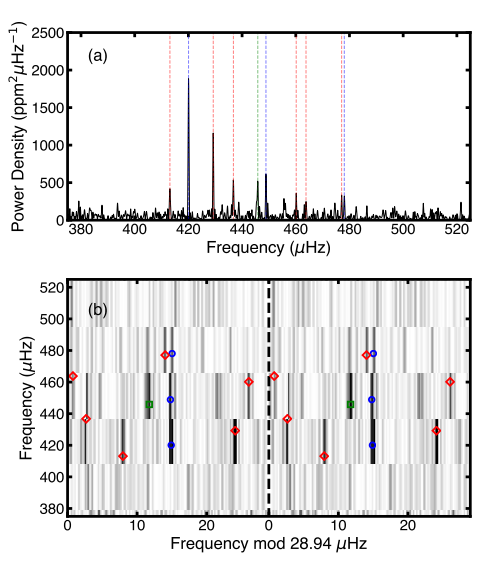

The authors converted the maximum power into amplitude and plotted this against the frequency of maximum power. Comparison against 1500 stars from the Kepler mission confirmed it had solar-like oscillations. Another important value is the large frequency separation, found by identifying the difference in frequency between the radial mode peaks. Figure 2 shows the radial mode peaks in blue and that the large frequency separation is 29.84 microHz.

Modelling stellar properties

The authors then used stellar evolution and oscillation codes to model the stellar properties. The luminosity for the models was calculated by combining the Gaia parallax with photometry from many different catalogues. They also input properties from spectral modelling – temperature, surface gravity (log g) and metallicity – and the individual frequencies and large frequency separation from asteroseismology. This resulted in two preferred models: i) a lower mass, older star (1.15 Msol, ~6Gyr) or ii) a higher mass, younger star (1.3Msol, ~ 4Gyr). An independent constraint on surface gravity from an autocorrelation analysis of the lightcurve favours a higher mass model. Thanks to asteroseismology, the final estimates of stellar parameters have small uncertainties: radius (2%), mass (6%), mean density (1%) and age (22%).

Characterising the planet

Using the mean stellar density from asteroseismology, the authors jointly fit the photometric and radial velocity data to obtain the planet properties, including period, radius and mass. Figure 3 shows photometric data (top) and radial velocity data (bottom), both phase folded on the best period of 14.3 days. The mass ratio is calculated from the maximum amplitude of the radial velocity data. Combining this with the modelled stellar mass gives a minimum planet mass 35% lighter than Saturn. The transit depth gives the radius ratio, which combined with the modelled star radius gives a planet radius the same as Saturn.

A Hot Saturn and a Bright Future!

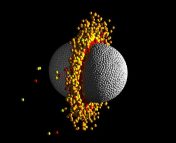

The result: TOI-197.01 is a hot Saturn orbiting a late subgiant/early red giant star. The combination of spectra and the large frequency separation from asteroseismology shows the star has just started ascending the red giant branch. TOI-197.01 represents the starting point before gas giants reinflate due to the strong flux from their evolved stars. This is significant as it is TESS’s first detection of a transiting planet orbiting a late subgiant/early red giant with detected oscillations, and only the sixth ever detected.

This is an exciting result as it shows that even with 27 days of data, TESS should allow us to study the oscillations of thousands of bright stars which have 2 minute cadence data. TOI-197.01 is also one of the most precisely characterised Saturn sized planets, with density constrained to 15%. This demonstrates what we can gain by ‘listening’ to exoplanet host stars.