Title: The unorthodox evolution of major merger remnants into star-forming spiral galaxies

Authors: Martin Sparre and Volker Springel

First Author’s Institution: Heidelberger Institut fur Theoretische Studien

Status: Submitted to Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Oct 2016

“…I was completely fine!

No really. There I was mindin’ my own business and, WHAM!

Galaxy, straight in the kisser, couldn’ta seen it coming.

Now I thought I was a gonner, end of days, whole life-before-the-eyes stuff.

But whatd’ya know. Gave it a couple of billion years and I felt right as rain!

No kidding, still ‘ad all me gas. Got a nice little disk going. Full recovery.

Now people will tell you, one big merger and you’re out. You’re an elliptical son. Round as a robin and dull as a thursday.

But look at me, never seen a better example of a spiral galaxy in ya life!”

It’s shaggy dog stories like this that ensure galaxies are never invited down the pub.

Galaxies crash into each other all the time. It’s almost embarrassing how accident prone they are. Even our own Milky Way is on a collision course with nearby Andromeda, though slapstick fans will have to wait another 4 billion years.

We call these collisions mergers (mostly to save the poor things from further mortification). Most of them are like a fly head-butting a moving car — one galaxy dwarfs the other so much it barely notices the collision. But occasionally the odds are fairer, and two similar mass galaxies collide.

And when that happens they tear each other apart. They send stars scattering in all directions. They fling all their gas out like a petulant child throwing their toys out of the pram. And eventually the whole mess settles back into a big swirling cloud of stars, an egg shaped bulge with no gas to form new stars, or do anything much at all for the rest of it’s lifetime.

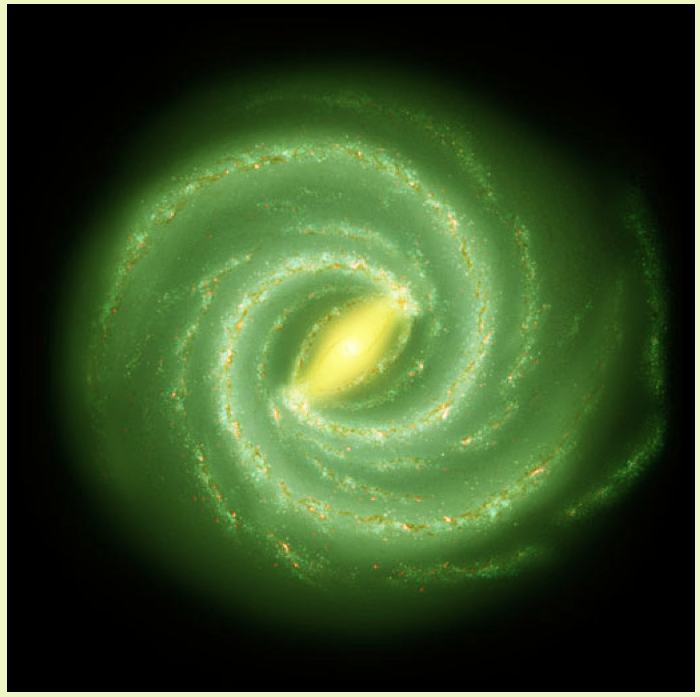

This underwhelming end result is called an elliptical galaxy. And destructive mergers like this are thought to be how spiral galaxies, beautiful razor thin disk-shaped galaxies like our own, end their life.

Left: A spiral galaxy, with long elegant arms in a elegant disk and new stars popping into life everywhichwhere. (shown from above) Right: An elliptical galaxy, which I’m officially petitioning to be renamed a star-blob. (shown from wherever, it’ll always just look like a smudge) Credit: Hubble/GalaxyZoo

Except… maybe not.

Galaxy collisions take such a long time (the speeds are huge, but the distances even greater) that we can only really study them in simulations. We take all the physics we know, tell a computer how to replicate it, and watch as the universe evolves.

But there are limitations, to simulate as complicated a thing as a universe takes time. If we’re not careful it might even evolve slower than the real thing, so we have to cut some corners. We’d love to follow every single particle as it bounces about the cosmos, but modern computing power limits our scope (things are getting better though!). Instead our smallest unit, the tiniest particle in our simulations, needs to represent not single atoms but billions of stars worth of gas.

But the fear is always that in this massive simplification, this grand-scale zoomed-out view of the universe, we’ll loose crucial detail.

The EAGLE simulation follows attempts to follow the full history of our universe. It goes from the huge-scale dark matter web down to individual galaxies,. But where this galaxy should have trillions of individual stars, we can only model it with tens of thousands.

The idea that merging spiral galaxies form ellipticals comes from simulations like these, but what happens if we look a little closer?

That’s what the authors of this paper thought about. Then they stopped thinking about it because they’d done it.

Instead of following hundreds of thousands of galaxies, they picked just a few and simulated them at a range of resolutions.

When the galaxy is poorly resolved, and the fine detail is lost, mergers tend to completely wipe out any trace of a disk. But the better resolved the galaxy is, the more we see that after the merger the disk begins to regrow itself. Given enough time, the galaxy, temporarily so disrupted as to look like the star-blob above, recovers its razor thin disk of gas and stars.

Rather than being completely disrupted, the spiral galaxies seem to survive the encounter. Not only do they retain their characteristic shape, but they hold onto enough of their gas that even after the collision they can still form new stars and shine brightly in the night sky.

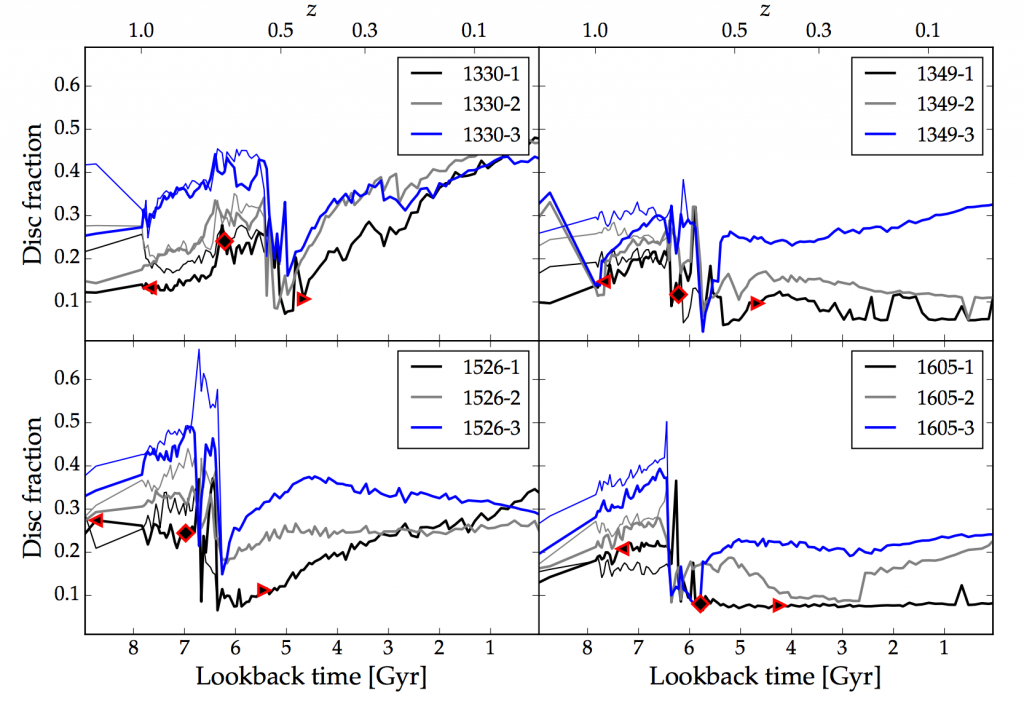

The more stars that reside in a thin disk (the y-axis) the more it resembles a spiral galaxy. Four galaxies are simulated, at roughly the same resolution as EAGLE (black), 4x times more detail (grey) and 40x more deatil (blue). Following the evolution in time from left to right we see the galaxies are spun up as they approach, then nearly completely disrupted as they merge (with a sharp drop in disk fraction). Then, for the higher resolution simulations, bit by bit the disk recovers over time, especially clear in the rightmost panels. Figure from the paper.

The question of why the more detailed simulations lead to more indestructible spirals is an open one. If I had to put money on it, I’d say that the disk is regrown from gas falling in from outside the galaxy, and that at low resolutions this gas is all blown away during the merger.

Luckily though, astronomy’s not a betting game. Our simulations are improving all the time, and it won’t be long until we can pick away at this little mystery. Once we understand the conditions necessary to create the full spectrum of galaxies, we can look at the night’s sky today and work out it’s history. Watch this space.

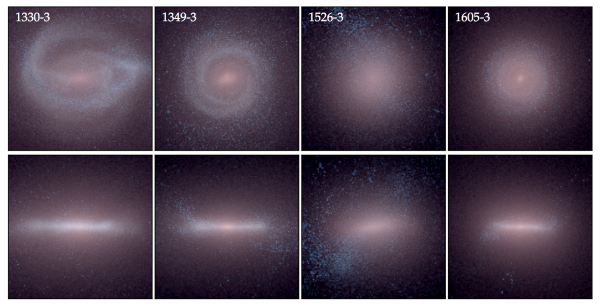

Images of the galaxies after the merger, taken at the end of the highest resolution simulations. The top row is the view from above, and the bottom row from the side. All show signs of recovering a disk, the first two appearing the most like a spiral galaxy and the third looking the most disrupted. From the paper.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks